![]()

“How Modern Artists Caught the Doodle Bug.” Apollo, 18 April 2023.

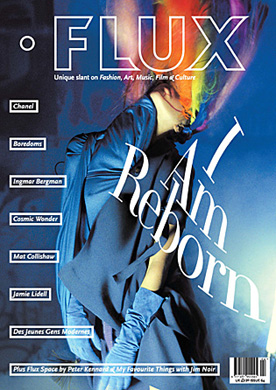

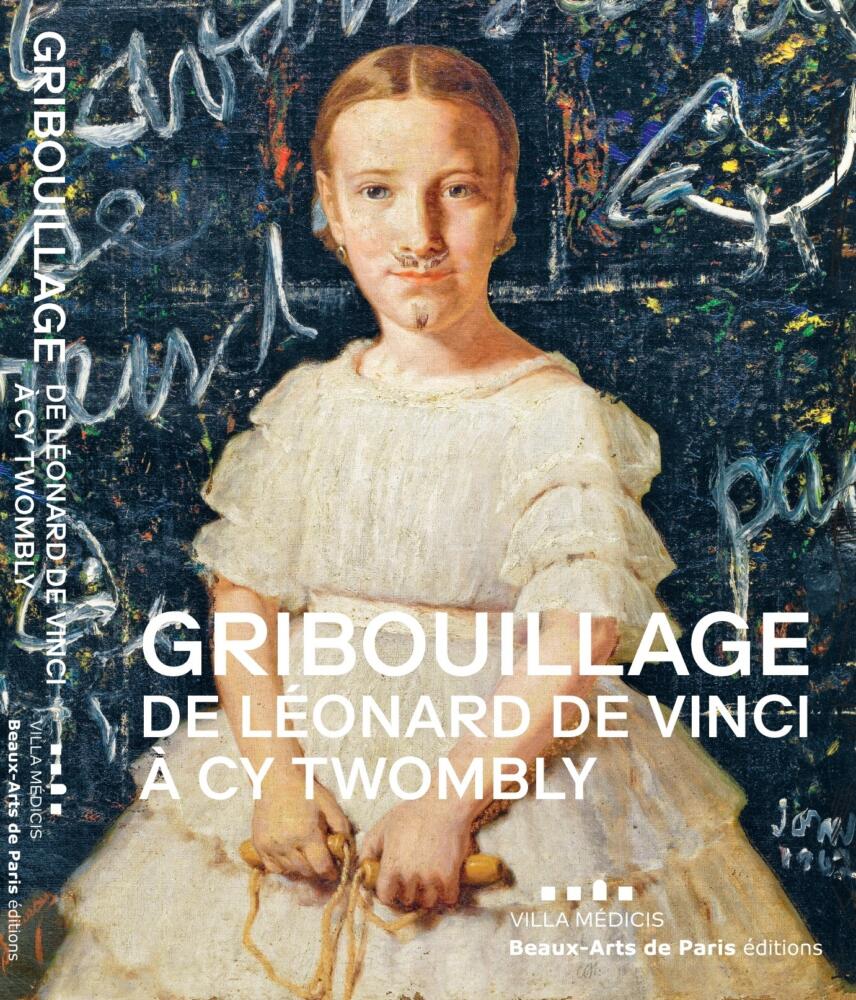

Imagine Dubuffet or Basquiat scrawling on the back of a Michelangelo and you get a good idea of the first impressions of a visitor to ‘Gribouillage/Scarabocchio: From Leonardo da Vinci to Cy Twombly’, currently at the Beaux-Arts de Paris. Curated by Francesca Alberti and Diane H. Bodart, the show explores the striking, perhaps even disquieting resemblance between doodles discovered on works by the Renaissance masters and those of modern artists.

This sumptuously presented exhibition maintains an achronological arrangement throughout. The antique cast of a profile carved into a segment of wall from Alberto Giacometti’s Paris studio hangs cheek by jowl, at the entrance, with the drawing of another profile, discovered — along with a profusion of small but intricate sketches — behind a fresco by Benozzo Gozzoli (1471–72). On a nearby partition, works by Cy Twombly (1967) are flanked by Claude Lorrain drafts (1630) and a Delacroix lithograph (1827), its thick borders alive with the artist’s marginalia.

The question that hangs over the entire exhibition is whether the doodles of the past should be interpreted in the light of artistic modernity. In the Renaissance, prevailing wisdom dictated that the hand was the instrument of reason. By contrast, Leonardo da Vinci himself described his sketching technique as componimento inculto — literally, uncultivated compositions. Leonardo advocated letting go; allowing the hand to drift on the page — guided by happenstance or what we would now call the unconscious — until latent figures surface. The finest example of this vagabond style is Stefano della Bella’s 1648 study of a young man falling to his death, seemingly submerged by the swirling scribbles from which he emerges.

The exhibition abounds in variations on Leonardo’s template: André Masson’s surrealist automatic drawings, Robert Breer’s minimalist cartoon, A Man and His Dog Out for Air (1957), or Henri Michaux’s suitably hypnotic pieces produced under the influence of mescaline. Physical constraints are frequently adopted in pursuit of spontaneity: Salvador Dalí drawing while pleasuring himself; Willem de Kooning electing to draw with his left hand or with several pencils at the same time. A film of 1995 shows Robert Morris performing one of his numerous Blind Time compositions. The film finds an echo in Brassaï’s photograph of Henri Matisse from 1939, standing bold upright beside the face he has just scrawled on a door with closed eyes and a piece of chalk, while also calling to mind the spiritualism that inspired Victor Hugo’s ink sketches.

For Paul Klee, who naturally looms large here, the activities of drawing and writing were identical. Many of the works on display — those of Klee, Giacometti, Masson, Twombly, and Steinberg in particular — conjure up Roland Barthes’ famous essays on the artistic tradition of ‘illegible’ writing, which, he felt, held out the utopian promise of a world free from the tyranny of preordained meaning.

But the exhibition also revels in the subversive charge of doodling. The section where Renaissance sketches are presented vertically on counters — allowing you to see the official production on one side and the unofficial on the other — provides the illicit thrill of a peep show. Images are sometimes of a scatological or sexual nature. There are caricatures of cuckolds with outsize horns from the 17th century and photographs of criminals’ tattoos taken by the French police around the Second World War. A diminutive sketch by Michelangelo represents a young man defecating. James Ensor draws a man urinating against a graffitied wall on which someone has scrawled ‘Ensor is mad’! The artistic production of the mentally ill is explored, as well as that of bored office clerks and children. ‘It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child,’ said Picasso. Visiting this exhibition, one gets the impression that he was by no means the only one.

Like its subject matter, ‘Gribouillage’ is an irreverent, provocative and playful show, but it also reaffirms the power that doodles hold over us in the modern era. As George Steiner once remarked, ‘modernity often prefers the sketch to the finished painting’ — both because it gets us closer to the original inspiration of the artist and because it remains unfinished, in the process of becoming.

Here is a different, longer, unpublished version of the above review:

To misquote Borges, all artists create their own precursors. ‘Gribouillage de Léonard de Vinci à Cy Twombly’, currently at the Beaux-Arts de Paris, seems predicated on such a principle. The premise of this sumptuous exhibition, curated by Francesca Alberti and Diane H. Bodart, is the striking — at times even disquieting — resemblance between doodles discovered on works by the Renaissance masters and those of prominent modern artists. Imagine Dubuffet or Basquiat scrawling on the back of a Michelangelo and you get a good idea of the visitor’s initial impression, sustained by a studiously achronological arrangement, with ancient and modern juxtaposed throughout. The antique cast of a profile carved into a segment of wall from Alberto Giacometti’s Paris studio hangs cheek by jowl, at the entrance, with the drawing of another profile, discovered — along with a profusion of small but intricate sketches — behind a fresco by Benozzo Gozzoli (1471-1472). On a nearby partition, works by Cy Twombly (1967) are flanked by Claude Lorrain drafts (1630) and a Delacroix lithograph (1827), its thick borders alive with the artist’s marginalia. Thus reframed, should the doodles of yesteryear be reinterpreted à rebours, in the light of artistic modernity? This question, that hangs over the entire exhibition, is illustrated by Inge Morath’s black-and-white photograph of Giacometti holding up an empty frame to showcase a white figure daubed on his studio wall.

The existence of a rival tradition — whose origins may stretch back to the cave paintings painstakingly reproduced by Henri Breuil or the Pompeian graffiti photographed by Brassaï, both on display here — is embodied by Leonardo da Vinci himself. The sketching technique he described as componimento inculto — literally, uncultivated compositions — ran counter to the then prevailing notion that the artist’s hand should be the instrument of reason. Contrarily, Leonardo advocated letting go; allowing the hand to drift on the page — guided by happenstance or what we would now call the unconscious — until latent figures surface from the tohubohu. The finest example of this vagabond style is Steffano della Bella’s 1648 study of a young man falling to his death, seemingly submerged by the swirling scribbles he emerges from. Robert Breer’s minimalist cartoon, A Man and His Dog Out for Air (1957), comes a close second.

The exhibition abounds in variations on Leonardo’s template: André Masson’s surrealist automatic drawings, or Henri Michaux’s suitably hypnotic pieces produced under the influence of mescaline. Physical constraints are frequently adopted in pursuit of spontaneity: Salvador Dalí drawing while pleasuring himself; Willem de Kooning electing to draw with his left hand or with several pencils at the same time. A 1995 film shows Robert Morris, eyes wide shut, performing, as it were, one of his numerous Blind Time compositions. The latter echoes Brassaï’s 1939 photograph of Henri Matisse standing bold upright beside the face he has just scrawled on a door with closed eyes and a piece of chalk. (We are not far off from the spiritualism that inspired Victor Hugo’s ink sketches.) Svetlana and Igor Kopystiansky’s short film, Steps Sole Sound (1979), put me in mind of Robert Walser — the infamous picture of footsteps in the snow leading up to the dead writer’s prone body — or the Ann Quin character who abandons conventional art in favour of making ‘paintings with her footprints in the snow’.

Doodling, especially in the shape of scribbles and squiggles, lies at the intersection of art and writing. It is the liminal space where the one becomes the other. For Paul Klee, who naturally looms large here, both activities were identical. For most preliterate children too, presumably. Many of the works on display — those of Klee, Giacometti, Masson, Twombly, and Steinberg in particular — conjure up Roland Barthes’ famous essays on the artistic tradition of ‘illegible’ writing, which, he felt, held out the utopian promise of a world free from the tyranny of preordained meaning. The best way to sever the connection between hand and intellect is indeed by deactivating the communicative powers of language itself.

If doodling has gradually come out of the closet and taken centre stage, this sprawling exhibition manages to retain part of its subversive charge. The section where Renaissance sketches are presented vertically on counters — allowing you to see the official production on one side and the unofficial on the other — provides the illicit thrill of a peep show. Images are sometimes of a scatological or sexual nature. There are dick pics from the 16th century, caricatures of cuckolds with outsize horns from the 17th, and photographs of criminals’ tattoos taken by the French police around the Second World War. A diminutive sketch by Michelangelo represents a young man defecating. James Ensor draws a man urinating against a graffitied wall on which someone has scrawled ‘Ensor is mad’! The artistic production of the mentally ill is explored, as well as that of children or bored office clerks à la Bartleby.

Like its subject matter, ‘Gribouillage’ is an irreverent, provocative and ludic show, but it is also an important one. As soon as Western art ceased to be mere imitation of the great works of the past — as soon as it became modern — a glaring gap opened up between inspiration and execution. This is why, as George Steiner remarks, ‘modernity often prefers the sketch to the finished painting’. Not only does it seem closer to the source of origin, but its unfinished nature means that it remains in the process of becoming. Doodling preserves art’s potentiality by gesturing to a future finished work as yet untainted by instantiation.