![]()

“Meaningless violence may be the true poetry of the new millenium. Perhaps only gratuitous madness can define what we are” – J. G. Ballard, Super-Cannes

![]()

“Meaningless violence may be the true poetry of the new millenium. Perhaps only gratuitous madness can define what we are” – J. G. Ballard, Super-Cannes

![]()

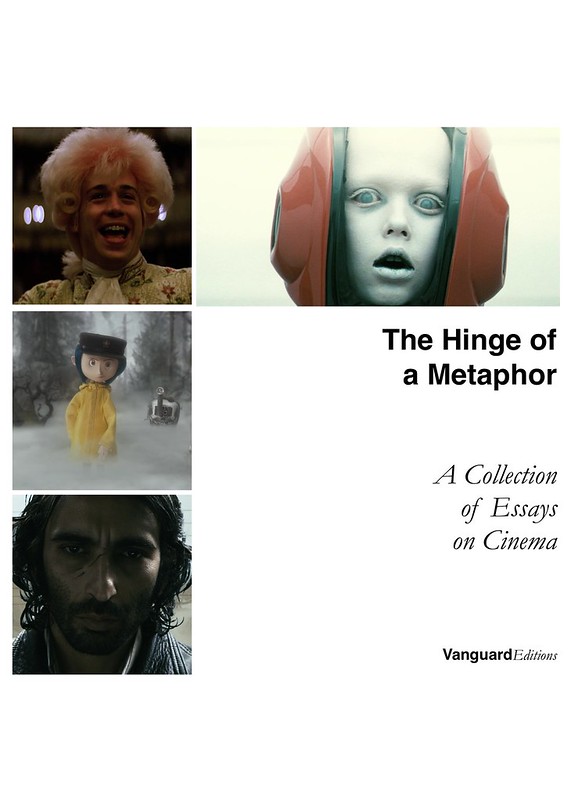

I have an essay on Olivier Assayas’s Après Mai and a near-death experience in The Hinge of a Metaphor, edited by Richard Skinner, which is now available from Vanguard Editions. With thanks to Mr Skinner!

![]()

“Haunted by the Music.” Review of August Blue by Deborah Levy, The Irish Times, 13 May 2023, p. 26.

A character in Swimming Home (2011), Deborah Levy’s breakthrough title, confides that she only enjoys biographies once the subjects have escaped “from their family, and spend the rest of their life getting over them”. In August Blue, her eighth novel, the author reprises this approach, but flips it round. The family Elsa is striving to get over is the one she never had, hence the question that haunts this book, lending it a spectral quality: how do you escape from the presence of absence?

Elsa M Anderson, the young protagonist, has quite a back story to contend with. Having been abandoned at birth by her mother, this piano prodigy was then “gifted” (authorial pun intended) by her foster parents to Arthur Goldstein, so that she could become a resident pupil at his prestigious music school. Goldstein, a diminutive but flamboyant aesthete, moulds his protégée into a virtuoso performer of international repute. He regards Elsa as his “child muse” rather than simply his child, encouraging her — through the cultivation of her talent — to dwell in a higher abode: “He meant a home in art”. The art of others is what he really meant. Although he cares for her deeply, as becomes apparent in his dying days, Goldstein discouraged Elsa’s “early attempts at composition”, threatened as he was by her ability to “hear something that he did not understand”.

Three weeks prior to the opening scene, this “something” — an “embryonic symphony” — had infiltrated the piano concerto Elsa was interpreting at Vienna’s Golden Hall. Her hands (insured for millions of dollars) “refused to play” the score despite the conductor’s baton-wielding histrionics: for a few minutes, Elsa “ceased to inhabit Rachmaninov’s sadness”, and dared to inhabit her own. She then walked off stage, sabotaging her career but reclaiming her life. As a prelude to this very public breakdown, she had dyed her hair blue, signalling a defiant “separation from [her] DNA”, but also from her mentor, whose “hostage” she had been since the age of six.

After rejecting the “old composition”, Elsa is free to dance to a new tune. An all-pervasive mood of “hyper-alert connections to everything” — not dissimilar to Levy’s adventurous free-associative prose — holds sway as she peregrinates through Athens, Paris, London and Sardinia. Her choice of creation (over interpretation) engenders a proliferation of duplications. Timelines overlap and locales collide in an intricate network of uncanny echoes exemplified by the ants that run along the rim of Elsa’s bath in both her London and Paris flats: “They had found a portal to all my worlds”. The non-binary teenager’s refusal to become their father’s “little me” likewise mirrors the heroine’s quest for identity and autonomy.

Elsa, however, is borne back into the past as she ventures into the future. The repressed returns in various guises, particularly in the shape of a pair of mechanical horses purchased by a young woman in an Athens flea market. These knick-knacks conjure up a recurring childhood memory — that of a piano being pulled by horses across a field — whose significance is slowly revealed to character and reader alike.

Not only does Elsa feel that the mechanical horses have somehow been stolen from her, but she is also convinced that the stranger at the market is in fact her doppelgänger. Although she is in her early 30s, like Elsa, and wears a very similar raincoat, the two women are in no way identical. Yet the protagonist seems to be in telepathic communication with this “psychic double” who, she believes, is stalking her across several countries. Elsa retrieves the hat the woman has forgotten, vowing to hand it back in exchange for the totemic horses.

The extent to which the doppelgänger is merely a figment of her lonely imagination, an idealised version of herself (“Perhaps she was a little more than I was”), or even her polar opposite in some parallel quantum universe remains open to interpretation. With her “attitude and confidence”, she certainly seems to embody the self-composure that the newly emancipated Elsa aspires to: “Perched between her lips was a fat cigar. Glowing at the end. It was a poke at life. A provocation”. At times, this “unlikely double” almost seems to merge with another phantom figure — that of the birth mother.

“My words were smaller than my feelings,” Elsa laments. The novelist’s achievement is to have found words equal to hers. Deborah Levy is now regarded as a grande dame of literature, but she remains as vital as ever, and August Blue is a mistresspiece.

© Andrew Gallix

![]()

Me and Sam Mills, National Gallery, May 2023.

![]()

The wine bar we used to go to so often is no longer there — and neither are you, Mum, or Amis.

![]()

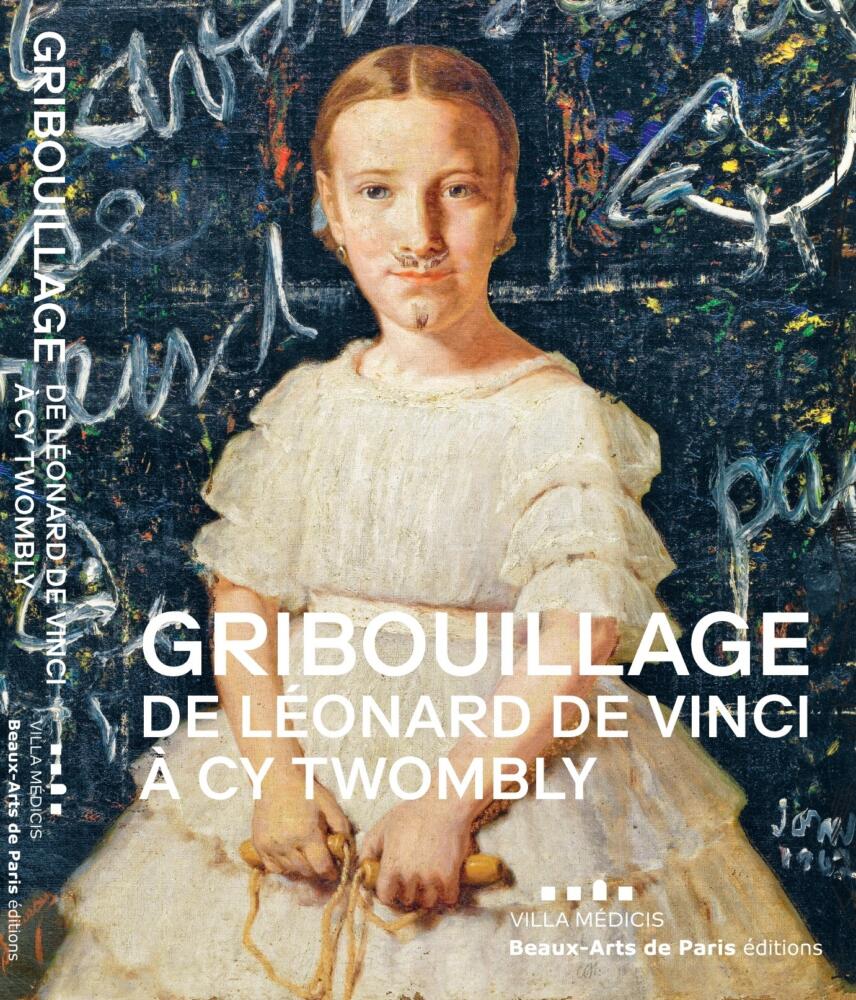

“How Modern Artists Caught the Doodle Bug.” Apollo, 18 April 2023.

Imagine Dubuffet or Basquiat scrawling on the back of a Michelangelo and you get a good idea of the first impressions of a visitor to ‘Gribouillage/Scarabocchio: From Leonardo da Vinci to Cy Twombly’, currently at the Beaux-Arts de Paris. Curated by Francesca Alberti and Diane H. Bodart, the show explores the striking, perhaps even disquieting resemblance between doodles discovered on works by the Renaissance masters and those of modern artists.

This sumptuously presented exhibition maintains an achronological arrangement throughout. The antique cast of a profile carved into a segment of wall from Alberto Giacometti’s Paris studio hangs cheek by jowl, at the entrance, with the drawing of another profile, discovered — along with a profusion of small but intricate sketches — behind a fresco by Benozzo Gozzoli (1471–72). On a nearby partition, works by Cy Twombly (1967) are flanked by Claude Lorrain drafts (1630) and a Delacroix lithograph (1827), its thick borders alive with the artist’s marginalia.

The question that hangs over the entire exhibition is whether the doodles of the past should be interpreted in the light of artistic modernity. In the Renaissance, prevailing wisdom dictated that the hand was the instrument of reason. By contrast, Leonardo da Vinci himself described his sketching technique as componimento inculto — literally, uncultivated compositions. Leonardo advocated letting go; allowing the hand to drift on the page — guided by happenstance or what we would now call the unconscious — until latent figures surface. The finest example of this vagabond style is Stefano della Bella’s 1648 study of a young man falling to his death, seemingly submerged by the swirling scribbles from which he emerges.

The exhibition abounds in variations on Leonardo’s template: André Masson’s surrealist automatic drawings, Robert Breer’s minimalist cartoon, A Man and His Dog Out for Air (1957), or Henri Michaux’s suitably hypnotic pieces produced under the influence of mescaline. Physical constraints are frequently adopted in pursuit of spontaneity: Salvador Dalí drawing while pleasuring himself; Willem de Kooning electing to draw with his left hand or with several pencils at the same time. A film of 1995 shows Robert Morris performing one of his numerous Blind Time compositions. The film finds an echo in Brassaï’s photograph of Henri Matisse from 1939, standing bold upright beside the face he has just scrawled on a door with closed eyes and a piece of chalk, while also calling to mind the spiritualism that inspired Victor Hugo’s ink sketches.

For Paul Klee, who naturally looms large here, the activities of drawing and writing were identical. Many of the works on display — those of Klee, Giacometti, Masson, Twombly, and Steinberg in particular — conjure up Roland Barthes’ famous essays on the artistic tradition of ‘illegible’ writing, which, he felt, held out the utopian promise of a world free from the tyranny of preordained meaning.

But the exhibition also revels in the subversive charge of doodling. The section where Renaissance sketches are presented vertically on counters — allowing you to see the official production on one side and the unofficial on the other — provides the illicit thrill of a peep show. Images are sometimes of a scatological or sexual nature. There are caricatures of cuckolds with outsize horns from the 17th century and photographs of criminals’ tattoos taken by the French police around the Second World War. A diminutive sketch by Michelangelo represents a young man defecating. James Ensor draws a man urinating against a graffitied wall on which someone has scrawled ‘Ensor is mad’! The artistic production of the mentally ill is explored, as well as that of bored office clerks and children. ‘It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child,’ said Picasso. Visiting this exhibition, one gets the impression that he was by no means the only one.

Like its subject matter, ‘Gribouillage’ is an irreverent, provocative and playful show, but it also reaffirms the power that doodles hold over us in the modern era. As George Steiner once remarked, ‘modernity often prefers the sketch to the finished painting’ — both because it gets us closer to the original inspiration of the artist and because it remains unfinished, in the process of becoming.

Here is a different, longer, unpublished version of the above review:

To misquote Borges, all artists create their own precursors. ‘Gribouillage de Léonard de Vinci à Cy Twombly’, currently at the Beaux-Arts de Paris, seems predicated on such a principle. The premise of this sumptuous exhibition, curated by Francesca Alberti and Diane H. Bodart, is the striking — at times even disquieting — resemblance between doodles discovered on works by the Renaissance masters and those of prominent modern artists. Imagine Dubuffet or Basquiat scrawling on the back of a Michelangelo and you get a good idea of the visitor’s initial impression, sustained by a studiously achronological arrangement, with ancient and modern juxtaposed throughout. The antique cast of a profile carved into a segment of wall from Alberto Giacometti’s Paris studio hangs cheek by jowl, at the entrance, with the drawing of another profile, discovered — along with a profusion of small but intricate sketches — behind a fresco by Benozzo Gozzoli (1471-1472). On a nearby partition, works by Cy Twombly (1967) are flanked by Claude Lorrain drafts (1630) and a Delacroix lithograph (1827), its thick borders alive with the artist’s marginalia. Thus reframed, should the doodles of yesteryear be reinterpreted à rebours, in the light of artistic modernity? This question, that hangs over the entire exhibition, is illustrated by Inge Morath’s black-and-white photograph of Giacometti holding up an empty frame to showcase a white figure daubed on his studio wall.

The existence of a rival tradition — whose origins may stretch back to the cave paintings painstakingly reproduced by Henri Breuil or the Pompeian graffiti photographed by Brassaï, both on display here — is embodied by Leonardo da Vinci himself. The sketching technique he described as componimento inculto — literally, uncultivated compositions — ran counter to the then prevailing notion that the artist’s hand should be the instrument of reason. Contrarily, Leonardo advocated letting go; allowing the hand to drift on the page — guided by happenstance or what we would now call the unconscious — until latent figures surface from the tohubohu. The finest example of this vagabond style is Steffano della Bella’s 1648 study of a young man falling to his death, seemingly submerged by the swirling scribbles he emerges from. Robert Breer’s minimalist cartoon, A Man and His Dog Out for Air (1957), comes a close second.

The exhibition abounds in variations on Leonardo’s template: André Masson’s surrealist automatic drawings, or Henri Michaux’s suitably hypnotic pieces produced under the influence of mescaline. Physical constraints are frequently adopted in pursuit of spontaneity: Salvador Dalí drawing while pleasuring himself; Willem de Kooning electing to draw with his left hand or with several pencils at the same time. A 1995 film shows Robert Morris, eyes wide shut, performing, as it were, one of his numerous Blind Time compositions. The latter echoes Brassaï’s 1939 photograph of Henri Matisse standing bold upright beside the face he has just scrawled on a door with closed eyes and a piece of chalk. (We are not far off from the spiritualism that inspired Victor Hugo’s ink sketches.) Svetlana and Igor Kopystiansky’s short film, Steps Sole Sound (1979), put me in mind of Robert Walser — the infamous picture of footsteps in the snow leading up to the dead writer’s prone body — or the Ann Quin character who abandons conventional art in favour of making ‘paintings with her footprints in the snow’.

Doodling, especially in the shape of scribbles and squiggles, lies at the intersection of art and writing. It is the liminal space where the one becomes the other. For Paul Klee, who naturally looms large here, both activities were identical. For most preliterate children too, presumably. Many of the works on display — those of Klee, Giacometti, Masson, Twombly, and Steinberg in particular — conjure up Roland Barthes’ famous essays on the artistic tradition of ‘illegible’ writing, which, he felt, held out the utopian promise of a world free from the tyranny of preordained meaning. The best way to sever the connection between hand and intellect is indeed by deactivating the communicative powers of language itself.

If doodling has gradually come out of the closet and taken centre stage, this sprawling exhibition manages to retain part of its subversive charge. The section where Renaissance sketches are presented vertically on counters — allowing you to see the official production on one side and the unofficial on the other — provides the illicit thrill of a peep show. Images are sometimes of a scatological or sexual nature. There are dick pics from the 16th century, caricatures of cuckolds with outsize horns from the 17th, and photographs of criminals’ tattoos taken by the French police around the Second World War. A diminutive sketch by Michelangelo represents a young man defecating. James Ensor draws a man urinating against a graffitied wall on which someone has scrawled ‘Ensor is mad’! The artistic production of the mentally ill is explored, as well as that of children or bored office clerks à la Bartleby.

Like its subject matter, ‘Gribouillage’ is an irreverent, provocative and ludic show, but it is also an important one. As soon as Western art ceased to be mere imitation of the great works of the past — as soon as it became modern — a glaring gap opened up between inspiration and execution. This is why, as George Steiner remarks, ‘modernity often prefers the sketch to the finished painting’. Not only does it seem closer to the source of origin, but its unfinished nature means that it remains in the process of becoming. Doodling preserves art’s potentiality by gesturing to a future finished work as yet untainted by instantiation.

![]()

I am saddened to hear of the passing of immensely talented and erudite Argentinian author Luis Chitarroni. Although we never actually met, I had the privilege to interview him via email for gorse magazine, ten years ago, in 2013. You can read the whole interview here.

Luis was extremely kind about my long-winded questions:

“Yours is, honestly, the best interview — the most careful, the most intelligent, the most precise — I’ve been invited to answer. Thanks to your collaboration, the result could read as a real companion to The No Variations.”

He even went on to say:

“Your questions, as I told you, were the best reading of the book someone has ever done (including all the Argentine and Spanish critics). I’m flattered by your curiosity, and shattered by your intelligence and intellectual comprehension. Thanks to these qualities, I reread The No Variations, and developed a kind of No Variations Companion.”

![]()

Lester Square and Friends. “The Space Between the Notes.” Taps, Cubist Records, 2023.

Lester Square was the original guitarist in Adam and the Ants and went on to co-found the Monochrome Set. So you can imagine how thrilled I was when he asked me to contribute to this project alongside the likes of Toby Litt, Nicholas Blincoe and John Robb.

Here’s the press release:

The English affection for miniatures has a long history: Nicholas Hilliard, John Hoskins and Samuel Cooper to name but a few. In the world of literature, critic Colin Manlove observed “The growing pleasure of English writers in creating fantastic miniature worlds which work on their own.”

It may be that those who live upon a small island take delight in small things.

In 2022, having tired of a solitude born of Covid 19, Lester Square emerged blinking into the light and, desperate for company, laid down a challenge to a number of eminent authors of his acquaintance to provide a short story: short enough to leave room for a musical backdrop to provide an expressive counterpoint and intriguing enough to elicit full immersion in a pocket otherworld: as William Blake would describe it, seeing “a world in a grain of sand.”

The process couldn’t have been simpler, collaborators merely sent in a sound file of their reading recorded on a phone. The challenge then for Lester was to set them to music and sound collage which complemented and amplified the mood conjured up by the written word. Sometimes literally — the rhythmic headboard banging as the neighbours have sex next door to Andrew Gallix; sometimes through counterintuitive juxtaposition — the jolly counterpoint to a skinhead attack in Lucy O’Brien’s memoir.

The collision and interplay of genres has resulted in 13 evocative vignettes – some magical, some comical, some foreboding – that have become more than the sum of their miniature parts

…but which leave you wanting more.

Full line-up (in order of appearance): Alan Platt, Michele Kirsch, John Robb, Lucy O’Brien, Nicholas Blincoe, Toby Litt, Paul D Brazill, Lobby Robinson, John Haney, Andrew Gallix.