![]()

Me, Serbia, some time between 1998 and 2000.

![]()

Albert Rolls. “The Nothing-Something of Loren Ipsum.” Review of Loren Ipsum by Andrew Gallix, 3:AM Magazine, 24 October 2025.

As Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Claudius’s reign progress toward their denouement, Ophelia, now mad, presses her way into the royal presence. A gentleman, advising Queen Gertrude to give her an audience, observes,

Her speech is nothing, Yet the unshaped use of it doth move The hearers to collection. They aim at it And botch the words up fit to their own thoughts; Which, as her winks and nods and gestures yield them, Indeed would make one think there might be thought…

The nothing-something described here emerges elsewhere in Shakespeare, for example, in Richard II, where it is portrayed as the anamorphic presence out of which Bolingbroke forms a political body in opposition to Richard II’s and becomes Henry IV. Laertes, who, the people cry, “shall be king,” seems to assume Bolingbroke’s structural position in Act IV of Hamlet but does not yield to the amorphous body of the people (1) and reshape it, thereby failing to become its head. He is instead re-absorbed into King Claudius’s graces and taken into the plot that will leave the stage scattered with royal corpses, the head of the political body reduced to the nothing-something that Fortinbras will be left to reshape so that he can become, in the parlance of Shakespeare’s day, Denmark, while Horatio is left to tell Hamlet’s story, to fashion a narrative analogue to the ordered state that we are likely meant to assume will rise in Claudius’s wake.

An ordered condition, the narrative variety in any case, has proven not to be the principal interest of the state that emerges after the intervention of King Hamlet, the ghost of the prince’s father and Shakespeare’s spirit, to borrow, if unfashionably and only metaphorically, from Harold Bloom’s Hamlet: Poem Unlimited with a wink at the grander titled Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human (2). We might call this state modernity, noting it’s not likely the one Shakespeare and his contemporaries sought to produce (3), and posit that Ophelia’s nothing-something, involving as it does the interaction between speech and listeners (text and readers), provides the most significant point of fascination for those of us stranded in modernity’s most recent iteration, an iteration in which “we locate modernity in the past,” as Loren Ipsum, the eponymous character of Andrew Gallix’s debut novel, observes.

Gallix’s novel explores a nothing-something analogous to the one Ophelia’s utterings become, asking in its first chapter, “what is lost when nothing is lost? When it becomes something?” The question here, posed by the novelist Sostène Zanzibar, refers to a note that reads “NOTHING IS LOST” and is found on the corpse of the murdered, we learn later, “Solange de la Turlute, the controversial boss of one of France’s largest family-owned publishing houses,” the first in series of murders, mostly of authors. But the question resonates beyond this context and seems to serve as the grounding question of the entire novel, “the book you are currently reading, which . . . is not the book I wanted to write,” the author, Adam Wandle — whom Ipsum is in Paris researching for a book and whose works provide slogans for the group behind the murders — asserts, but in such a way as to make ”the porous borders” between character — here Wandle — and author —Gallix (4) — “almost indistinguishable,” to appropriate phrases of a passage from Loren Ipsum that blurs, in a different manner, the distinction between fictional and nonfictional worlds.

The book he wanted to write was to “contain not only multitudes but everything,” a description of his desire that suggests “the book you are currently reading” is associated with a nothing-something in a classical sense, for Plato equated a term meaning “all” or “everything” with cosmos, as T. McAlindon notes in Shakespeare’s Tragic Cosmos, so that its opposite, “the word ‘nothing’ or ‘nought’ became another word for ‘chaos,’” the primordial nothing-something from which the cosmos was created and the liminal state in the metamorphic process in the post-creation world, or, as Gallix describes it in reference to a site of logical contradiction the “negation of the world that leads to the rise of a new one,” an end that is aligned with the figure of Zanzibar, who emerges as a supplement to Ipsum, another character who seems to blur into Gallix, for example, when Ipsum, on page 289, ends an interruption of a discussion about her debut novel and returns to her conversation with “‘Where were we? Ah yes, that passage on page 289…,’” a joke that seems to assume that the pagination won’t be changed in future printings. The number, of course, could be altered to match any page on which the passage appears, a maneuver that would provide a fitting element of instability to the text and perhaps oblige the original to supplement the repetition (and vice versa) to tease out its significance (5).

The dynamic I am here positing between the original and its supplemental repetition finds clearer expression when Ipsum attends the exhibit titled L’appel du vide (The Call of the Void), an exhibit in which Zanzibar participates, falling asleep and dreaming Ipsum, the dream version of whom dreams him. Gallix here provides a set of framing devices, one inside the other: the critic’s dream of the novelist is framed by the novelist’s dream of the critic, which is framed by the exhibit watched by the critic within the novel, Loren Ipsum. Author and critic even merge within the episode, for Ipsum briefly assumes the perception of an omniscient narrator — an authorial doppelgänger, if ever there were one — who, as she watches Zanzibar dream, thinks, “there is nothing more tiresome than other people’s dreams, especially in bloody books. I mean, how much pointless made-up pseudo-surreal slash absurdist shit can you stomach, for fuck’s sake?”

The concerns over the significance of the dream are wrong, serving rather as an anticipatory misreading that is meant to deter the reader from regarding the episode as a repetition of a tired trope, tired repetition being among the novel’s anxieties, the one that compels it to strive to situate itself in the liminal state of nothing-somethingness. The issue is played out in the trajectory that Zanzibar’s career takes, his successful debut, Je suis la Femme Bigorneau (1986) having been followed with four novels that “resembled an increasingly faded photocopy of the original blueprint [that is, Bigorneau], giving rise to …‘a sense of perpetual déjà vu on a dimmer switch,’” a sign of stagnation that Zanzibar seeks to escape through writing a “prequel to Genesis,” literally the story of primordial nothingness — something that can only be described by way of negation. The project comes to nothing, all drafts being destroyed.

Interestingly, the stagnation Zanzibar experiences has its analogue in a more ideal version of the creative process, the one that Wandle finds himself following, that is, writing stories “while looking for the story” (emphasis added), the profound tale that came to him one night — making him feel as if he “had been singled out, in the grand tradition of Plato’s Ion” — but that he had forgotten. “This may be the very source of all literature,” he muses. Zanzibar, in the absence of the “epiphany” that visited Wandle and intent on producing something like his Genesis prequel, arrives at “the concept of a novel printed in disappearing ink. Once read, each word would vanish forever, the full text living on in people’s minds — retold, reinterpreted, reinvented” in the tradition, perhaps, of Ophelia and those hearing her. This concept would situate the reader in the position of Wandle’s idea of a writer trying to find the perfect story, the details of which have been forgotten. The idea of a novel printed with disappearing ink is, of course, abandoned due to its impracticality but is published as a facsimile of a novel that had been written in longhand with such ink. The object, commercially successful, comes to serve as a “handy memo pad,” the imagined retelling, reinterpreting, reinventing being replaced by text that records the momentarily needed but discardable ephemera of people’s days, the creative dialogue between text and its readers being abandoned in the name of commercial necessity.

Zanzibar’s creative difficulty is one that Loren Ipsum, the novel, overcomes by pushing its apparent stories — the one about terrorists’ murdering writers and the one about the attempt to “make it to the mythical Blue Island,” both of which are described on the back cover of the paperback — into the background. The reader, it is true, is provided with firsthand accounts of some of the murders, one of which is narrated in the second person, and may catch a glimpse of the Blue Island, but the experience of the murder plot and the quest plot remains secondhand, comparable to the story of a serial killer in another country or of a vaguely interesting voyage of discovery that one half attends to in media accounts while going about one’s daily life. The novel, for example, never lingers on the scenes of the murders so that a narrative related to them can emerge. A negative stand-in for Horatio, in fact, shows up in the guise of Horatia, the apparent daughter of Jonathan Titterington-Jones, the writer whose murder is narrated in the second person. She remains disinterested, and her father is left to wonder, “At what point, if any, would [she] look up from her mobile and interrupt Cosimo’s [her brother’s] video game to enquire where you are?” Her focus is not “you,” so she can’t be relied on to fashion a story analogous to the one Hamlet asks Horatio to tell.

Loren Ipsum is a-not-quite lorem ipsum, a dummy text used to design pages. The novel’s pages have comprehensible text, but the story it purports to be about remains in a liminal state, waiting to be “retold, reinterpreted, reinvented.” Readers are to become, in short, Lorens, that is, critics whom the novelist dreams and who in turn dream the novelist.

Notes

(1) I am alluding here to Laertes’ warning to Ophelia to be careful about getting involved with Hamlet: He may not, as unvalued persons do, Carve for himself, for on his choice depends The safety and the health of this whole state. And therefore must his choice be circumscribed Unto the voice and yielding of that body Whereof he is the head.

(2) Shakespeare, it is believed, played the ghost of Hamlet’s father, the figure who gives birth to the plot and who serves, in Bloom’s reading, as Shakespeare’s spirit. Bloom’s assertion that “Hamlet has become the center of a secular scripture” — a text related to the secular world as the Bible, for example, is related to Christendom — thereby suggests that Hamlet and its spirit gave birth to our secular world, inventing us so to say.

(3) For example, in the Novum Organum, Francis Bacon explains, “there is a great difference between the idols of the human mind and the ideas of the divine mind; that is to say, between certain empty opinions and the genuine signatures and marks impressed on created things.” Bacon’s development of the scientific method, this observation suggests, was an effort to fill the gap that separated the hermeneutics and semiology of the sixteenth-century episteme, the purpose, as Foucault describes it in The Order of Things, of learning during the age we have come to call early modern.

(4) Gallix has a novel in his past that he wanted to write but did not. His last book, Unwords, is described on the publisher’s website as “essays and reviews haunted by a phantom book the author never completed when he was in his twenties.”

(5) If, for example, the chapter appeared as the last excerpt in an anthology of twenty-first century fiction with text that read “on page 956” to match the page on which the passage appears in the anthology, the text would almost certainly be accompanied by a supplemental note that observed “in the original printing of the novel, the text read ‘on page 289,’ the page number on which it appeared in that text.”

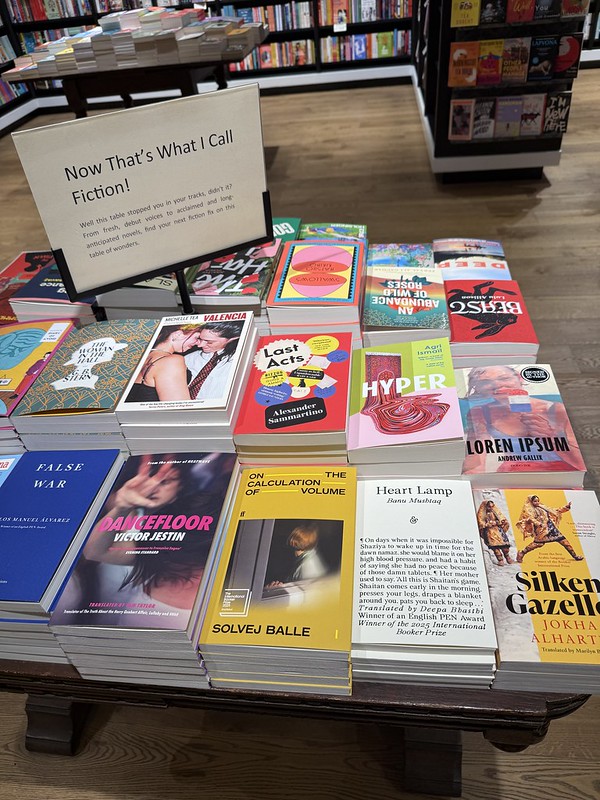

![]()

Loren Ipsum gets the thumbs-up from London-born, Paris-based Irish novelist & journalist Gerard Feehily!

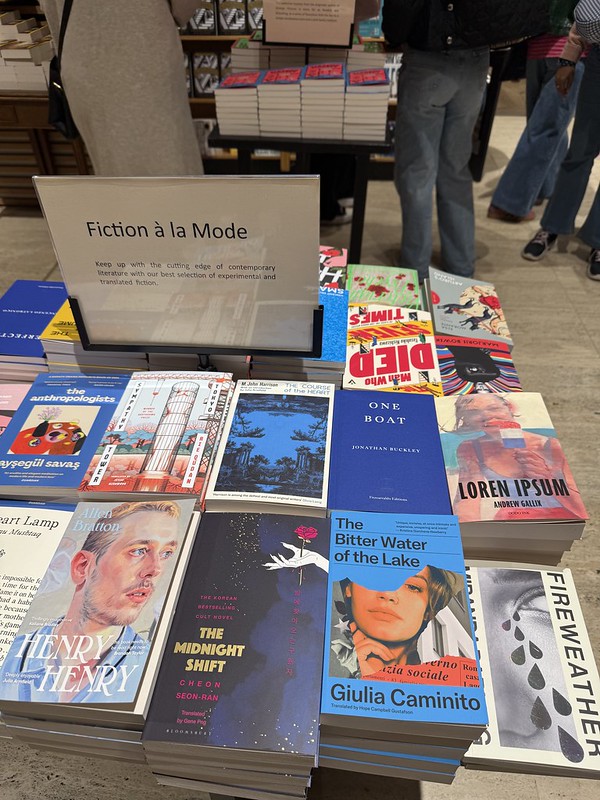

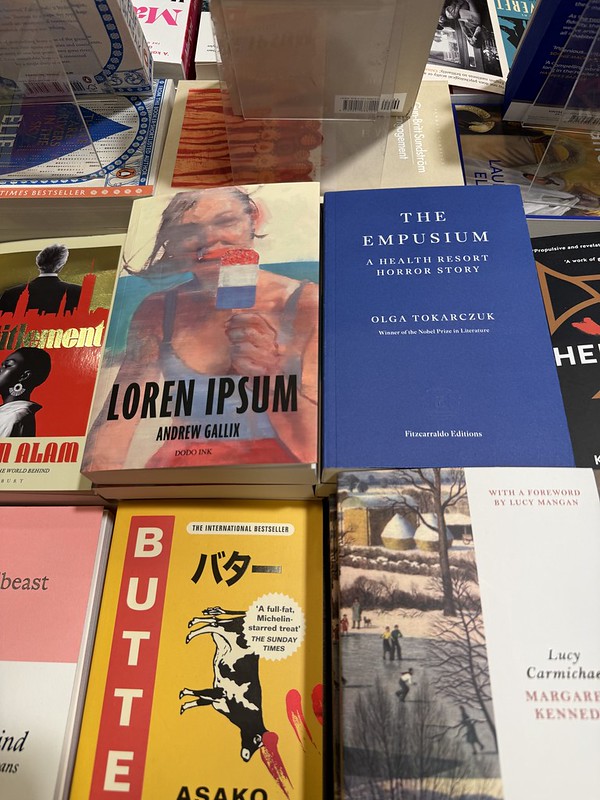

![]()

Loren Ipsum out in the wild (ie. London bookshops).

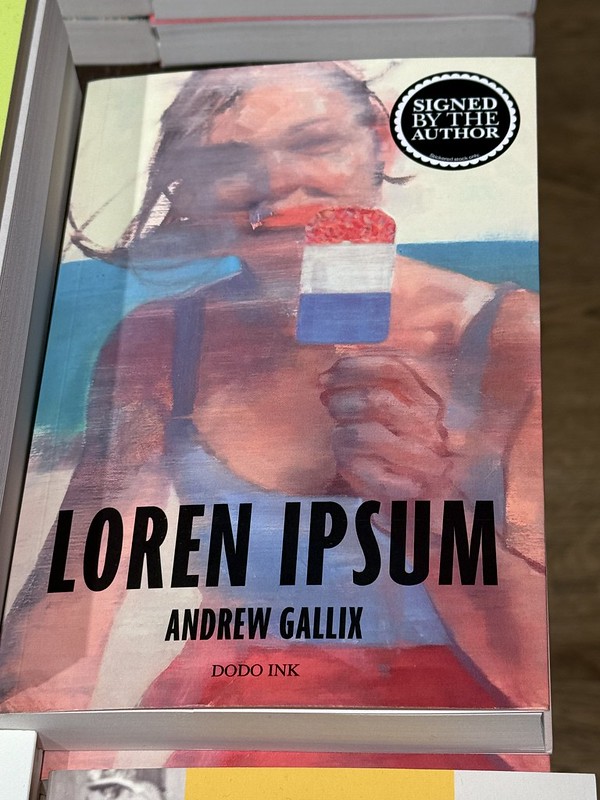

![]()

The launch of Loren Ipsum at Daunt Books Notting Hill on 9/11 was a great success despite the Tube strike. Thanks to all you lovely talented people who attended. Sam Jordison wrote: “That train ride I mentioned earlier was to go to the launch of this novel by the wonderful Andrew Gallix, editor of 3:AM magazine, and all round literary hero. It was a lot of fun… Well worth the journey, and a mad cycle ride across London among all the millions of people also out there on two wheels thanks to the Tube Strike”.