![]()

The name of a minor character in my novel, Loren Ipsum, was inspired by this cool signage I often walk past on rue Letort in the 18th arrondissement of Paris. (Instead of Goulet-Turpin, his surname is Turpin-Goulet.)

![]()

The name of a minor character in my novel, Loren Ipsum, was inspired by this cool signage I often walk past on rue Letort in the 18th arrondissement of Paris. (Instead of Goulet-Turpin, his surname is Turpin-Goulet.)

![]()

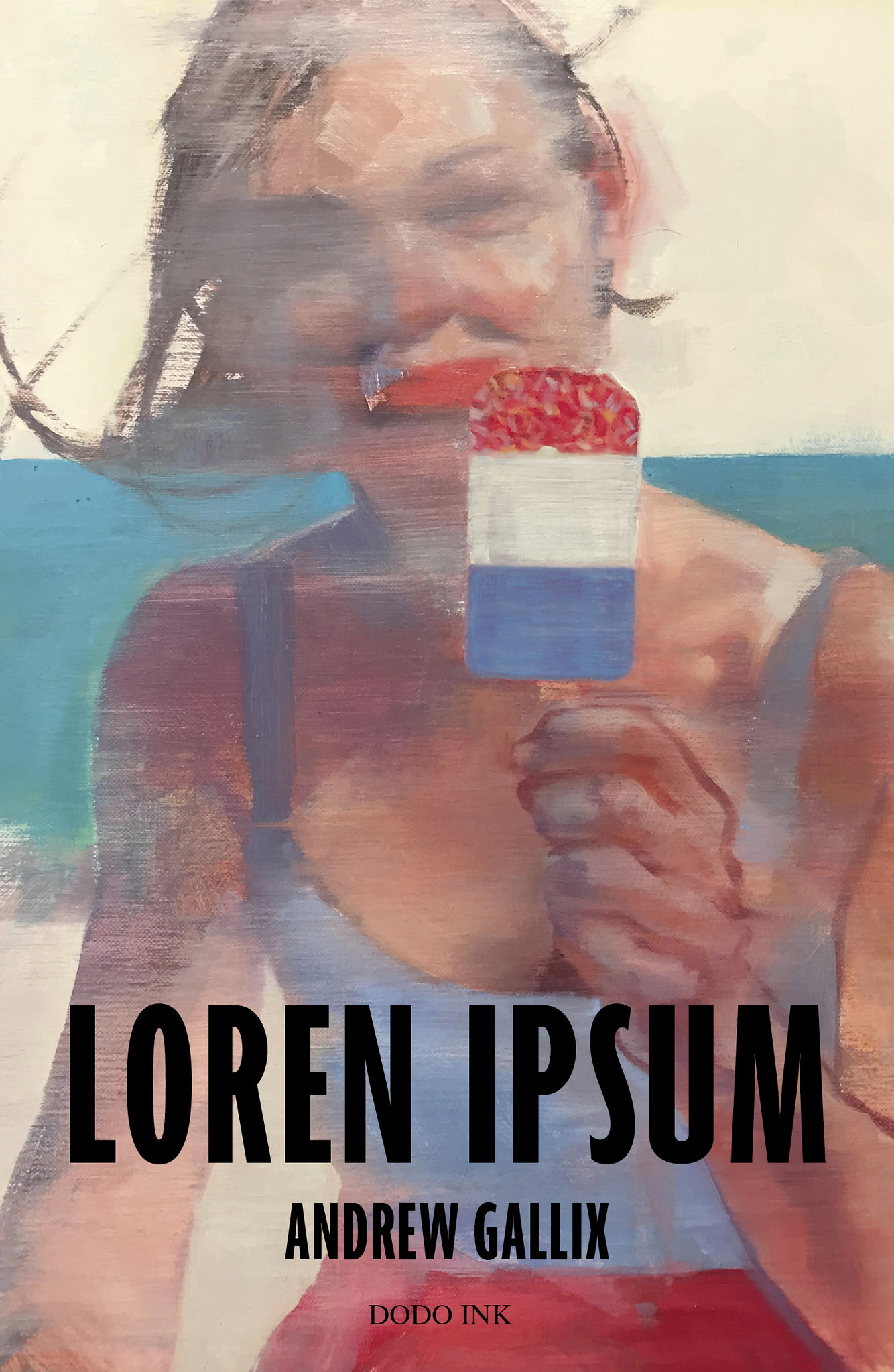

Jude Cook. “Vanity Fair.” Review of Loren Ipsum by Andrew Gallix, The Guardian, 15 November 2025.

A brilliant satire on the modern literary scene. Full of word games, in-jokes and grisly murders, this debut pours gleeful scorn on the pretensions of contemporary literary life

Freud would have had a lot to say about a novel in which the central premise is writers being murdered. A manifestation of a repressed desire to eliminate rival literary talent? A clear case of the death drive? Either way, there’s some twisted business going on in Andrew Gallix’s chronically funny debut novel, Loren Ipsum.

The morbid if intriguing premise quickly becomes secondary to an insouciant satire on the vanity fair of present-day literary culture. Not since Paul Ewen’s How to Be a Public Author has so much gleeful scorn for pretentious authors, critics and scenesters been poured on to the page. Taking its title from the placeholder text used while preparing a book for print, the novel features an eponymous protagonist, a journalist resident in Paris, who is researching a monograph on the reclusive English author Adam Wandle. Loren Ipsum somehow manages to be both the book’s moral centre and a shapeshifting cipher for everything that’s wrong with contemporary literary life. With “a heart of frosted glass”, she is “all blurred features and radio static”. Her own first novel, Fifty Shades of Grey Matter, was published by Galley Beggar in 2019. Her favourite bookshop is Shakespeare and Company (“she had all their totes”), and her best party frock is “part Mondrian, part Battenberg”. The knowing list of Loren’s favourite things is peak Bougie London Literary Woman and wickedly spot-on. It’s that kind of book. By the end, you can’t see the modernism for all the posts fencing it in.

As the death toll of Paris’s resident scribes rises, an obscure terrorist group claims responsibility, though their motives are unclear. Happily, the location moves to Antibes, where the carnivalesque action can continue. When Loren joins a literary party on a yacht, there’s a clear nod to Fellini’s 8½, with its melancholy cavalcade of posturing parvenus. Marcello Mastroianni himself makes a cameo later in a passage devoted to Le Tournon, the Parisian cafe where Joseph Roth drank himself to death and where Wandle goes to hide and write his ponderous prose.

Between these set-pieces there are whole chapters devoted to band names (“The Old Duffers, Omnishambles, The Opening Gambits”), and a heterogeneous cast of the great and the good: “Guy Debord in hot pursuit of a statuesque demi-mondaine modelling a lampshade hat … Gilles Deleuze doing the twist to Martha and the Muffins.” There are walk-ons from Andrew Wylie, Roland Barthes and Richard Hell, as well as Gallix’s own publisher, the author Sam Mills. There’s also the running gag of punning chapter titles: What We Talk About When We Talk About Talk; Quiet Days in Noisy; and my favourite, The Man Without Quality Streets. While some of the in-jokes overreach (“the cool clinking of the Žižek-shaped ice cubes”), others hit the spot with laser-guided accuracy. For instance, the moment when the immaculately named Sostène Zanzibar, “who had always tried and failed to convey the inadequacy of words with words”, comes up with the concept of a novel printed in disappearing ink.

Towards the end, the book takes a darker turn: “Shocking footage of a sensitivity reader, who had been tarred and feathered and then shackled to the railings on Mecklenburgh Square, was broadcast.” Then there’s the fate of the English writer Patrick Berkman, who moves to Montreuil but soon finds the banlieue population makes him feel he doesn’t belong, “just as they had been made to feel they did not belong in France”. He’s later found dismembered, his “puny body” partly devoured. Here, Gallix reinforces the notion that comedy is the best place to say something serious; in this instance, about France’s alienation of migrant communities. This is also evident in his unstoppable puns and word games. With their subversive, rebarbative edge, they stay just the right side of clever-clever.

Teeming with literary and pop cultural allusions and antic wordplay, Loren Ipsum ultimately stages a conversation about the uses, and possible uselessness, of literature. It has a nimble wit and a punk rock attitude that is wholly addictive. Destined, as they say, to become a cult classic.

![]()

Richard Clegg. “A Book with Meaningful Content.” Review of Loren Ipsum by Andrew Gallix, Bookmunch, 5 November 2025.

Prominent writers are being kidnapped and “executed” by terrorists who are convinced that bourgeois bohemians are the main obstacles to revolution today. Adam Wandle is a reclusive author who has been hiding out on the fringes of Paris. This is the plot but the plot isn’t everything in this novel. The novel is a companion piece to his critical book, Unwords, that covers prose fiction from Michel Butor to Jenn Ashworth.

It is brimful with puns, literary references, and exuberant humour, some sophisticated, some Carry On double entendres. Its elective affinities are as much with Beerbohm and Waugh as with Joyce and Proust. There are terrific lists of bands real or imagined and Chapter 13, a skit on book bloggers caught in a world of either/or that is neither moral or aesthetic, as far from Kierkegaard as it could possibly be. This isn’t a dummy text without meaningful content, a printing device that lorem ipsum means. It is a book with meaningful content.

If you like cryptic puzzles head for the bookshelf, if you like bonkers stories that meander everywhere, then this is the book for you. It is an unsettling read that includes a real life love story with Sam Mills, auto-fiction as well as the boyish ridiculous list: “No (a Yes cover band), Les Nombrilistes, The Nonplussed, The Nooks, No Shit Sherlock, The Noumena.”

Like the critical work Unwords, Loren Ipsum is a book you can dip into again and again. Read it once, then return in an endless loop that might feel part of a Tom McCarthy fiction.

Any Cop?: For Andrew Gallix this is his first foray into longer fiction. If this is his juvenilia I look forward to his middle years, and his late style. The exuberant critic has linked up with his double, the exuberant novelist.