Misremembering

“I do think something is lost today in the easily availability of films and music, and that’s the ability to misremember, or to forget. I’m not even sure why this seems important, but it does. Maybe there’s something about the distortion that comes with memory; there’s something valuable in the imaginative misremembering of our pasts which, relentlessly documented and archived now, live on in zombie-like ways in the present. That gap between the way things really were and the way we remember them to be is closing. If I had a gun against truth I’d use it every day.”

– Nicholas Rombes, Interview, Two Dollar Radio 7 January 2014

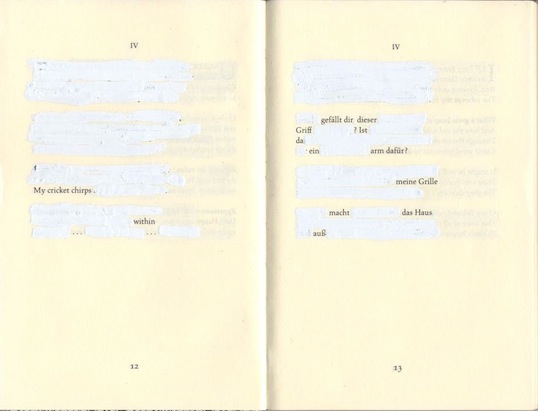

Liquid Paper

Ujana Wolf, “Whiting Out, Writing In, Or a Technique for Recording the Migratory Orientation of Captive Texts,” Asymptote October 2013

… Erasure, the reworking of found or selected texts by erasing most of the words, be it with the aid of correction fluid, ink, painting over or leaving out, oscillates between sabotage and homage, vandalism and reanimation. In Jen Bervin’s Nets, for example, all the words of the original text — Shakespeare’s sonnets — are still legible, yet most of them are printed in grey, almost faded away. They form a net, a shadow text, which can support the remaining words or at any moment lay itself protectively over them, as if they wanted to emerge briefly or themselves join in the disappearance. This curious tension is common to all erasures, the appearance of disappearance; they foreground — like concrete, experimental, lyrical, or language poetry — the materiality of language, of every single letter. They know that the space on the page is party to a text’s writing, a valve to let off steam, a white that structures silence, physically tangible,

notationen, reproduktionen von schnee

The World Without Me

This piece appeared in Necessary Fiction on 15 January 2014:

The World Without Me

He dives out of the water on to a lilo: finds himself mounting Mrs Robinson. Her eyes are closed. Her lips ajar. In this shot, Mrs Robinson reminds me of a pietà. Benjamin reminds me of an airborne penguin, exiting the ocean, and landing on its breast. Her breasts, in this instance, as well as his. His on hers — missionary position. Just before, Benjamin is seen doing the breaststroke underwater; swimming for dear life towards the safety of the lilo, as though pursued by some phantom shark (the lilo, of course, is the shark). Although the soundtrack is Simon & Garfunkel’s wistful “April Come She Will,” a post-1975 spectator cannot but hear the ominous two-note theme from Jaws underneath. It grows louder in the mind’s ear, rising to the surface with all the inevitability of tragedy. Benjamin falls as much as he leaps; flops down on his lilo-lady like one who has just been shot, or struck by lightning. Baudelaire likens the swain panting over his sweetheart to a dying man lovingly caressing his own gravestone — a couplet from “Hymn to Beauty” that is slightly misquoted in Truffaut’s Jules and Jim. Mrs Robinson is indeed the airbag that causes the crash; the wombtomb on which Benjamin (like that other Robinson) is marooned. The couple’s loveless affair is an accident that has been waiting to happen ever since Elaine — Mrs Robinson’s daughter, with whom Benjamin is destined to elope — was conceived in the back of a Ford. A Ford featured in J. G. Ballard’s Crashed Cars exhibition, held in a London gallery three years before the publication of his famous novel (Crash, 1973). The future sprouts fin tales. In the beginning, of course, was Marinetti’s car crash: “We thought it was dead, my good shark, but I woke it with a single caress of its powerful back, and it was revived running as fast as it could on its fins” (“The Futurist Manifesto,” 1909). Here, one thinks of Warhol’s series of silkscreened car crashes, Mrs Robinson having abandoned her arts degree due to her pregnancy.

Soon Benjamin will need to escape, choose some course of action. He is on a collision course with Elaine, the accident that has already happened. In the meantime, he is a castaway adrift upon shimmering amniotic fluid. A young man without qualities, in trunks and sunglasses, cradling a can of beer on his belly — Bartleby Californian-stylee. I like him best when he just goes with the flow; that is, when he goes nowhere. The camera lingers longingly on the texture of the ripples. Sunny constellations twinkle on the celestial water’s surface. Benjamin, recumbent on his lilo, fades out as the ever-morphing abstract of light reflections fades in.

The foregrounding of the background — putting the setting centre stage — is perhaps what cinema does best. In a movie, the world simply is whatever meaning the director attempts to project upon it. Neither meaningful nor meaningless, it is there and there it is. End of story. Reality reimposes itself, in all its awesome weirdness, through its sheer presence, or at least the ghost of its presence. Alain Robbe-Grillet (a filmmaker as well as a nouveau romancier) highlights the way in which cinema unwittingly subverts the narcotic of narrative; the auteur’s reassuring reordering of chaos:

In the initial [traditional] novel, the objects and gestures forming the very fabric of the plot disappeared completely, leaving behind only their signification: the empty chair became only absence or expectation, the hand placed on the shoulder became a sign of friendliness, the bars on the window became only the impossibility of leaving. …But in the cinema, one sees the chair, the movement of the hand, the shape of the bars. What they signify remains obvious, but instead of monopolizing our attention, it becomes something added, even something in excess, because what affects us, what persists in our memory, what appears as essential and irreducible to vague intellectual concepts are the gestures themselves, the objects, the movements, and the outlines, to which the image has suddenly (and unintentionally) restored their reality.

I want to write like Benjamin Braddock, from air mattress to pneumatic bliss in one impossible match on action.

Here is a passage from “Celesteville’s Burning” where I fail to do so:

When the ink ran out of her biro, Zanzibar produced a pencil from his inside pocket with a little flourish. ‘Men,’ he said, ‘alwez ave two penceuls.’ He almost winked, but thought better of it. ‘Women,’ she said a little later, sitting on his face, wearing nothing but her high-heeled boots, ‘always have two pairs of lips.’ She almost added Try these on for size, big boy, but thought better of it too.

I want to write like Benjamin Braddock, my words shipwrecked on the body they have been lured to. Eyes closed; lips ajar.

In an older short story — “Sweet Fanny Adams” — the protagonist happens upon a young woman in a railway station, and senses, instantly, that he has found his sense of loss:

Although he had never actually seen her before, he recognised her at once, and once he had recognised her, he realised he would never see her again. After all, not being there was what she was all about; it was the essence of her being, her being Fanny Adams and all that.

As he walked towards the bench where she was sitting pretty, Adam missed her already. Missed her bad.

‘How do you do?’

‘How do I do what? The imperfect stranger looked up from her slim, calf-bound volume and flashed him a baking-soda smile, all cocky like.

When my father took me to see The Graduate in the mid-70s, I was seized by a strange nostalgia for a homeland I had never known. In this sun-dappled “status symbol land” where charcoal is “burning everywhere” — as The Monkees sang on “Pleasant Valley Sunday,” released in 1967, the same year as the movie — I recognised my own sense of loss. The prelapsarian beach scenes in Jaws put me in similarly melancholy mood: all those healthy, happy families, and their dogs, enjoying spring break without (Roy Scheider excepted) a care in the world. Of course, a great white was about to blacken the mood somewhat, but I would experience this attack as the reenactment of an earlier trauma. The shark had already got me. Perhaps the shark has got us all, always-already.

A bespectacled woman wearing a hideous floral swimsuit and a floppy yellow hat detaches herself from the crowd massed at the edge of the sea. Like a Benjamin Britten character, she ventures into the water, calls out her son’s name, catches sight of his shredded lilo floating in a pale pool of blood. Her hat is a brighter shade of yellow than the lilo.

I reference this scene, albeit obliquely, in “Fifty Shades of Grey Matter”:

Valentin was lurking at the far end of the grand ballroom. He tried to picture himself à rebours, as though he were another, but failed to make the imaginative leap. A blinding flash of bald patch — the kind he occasionally glimpsed on surveillance monitors — was all he could conjure up: Friedrich’s Wanderer with rampant alopecia. He squinted at the polished floorboards, and slowly looked up as the world unfolded, leaving him behind. He was James Stewart in Vertigo; Roy Scheider in Jaws. He was the threshold he could never cross. At the far end of the grand ballroom Valentin was lurking.

Watching the world go by from a pavement cafe is a highly civilised activity, one we should all indulge in more often, I think. Its main drawback, however, is that we cannot abstract ourselves from the world we are observing. Like Valentin, we are the threshold we can never cross. There is a strand within modern literature that yearns for an experience of reality that would be untainted by human thought, language, and subjectivity. My hunch is that movies get closest to achieving this. As Stanley Cavell argues in The World Viewed, cinema provides access to a “world complete without me”:

A world complete without me which is present to me is the world of my immortality. This is an importance of film — and a danger. It takes my life as my haunting of the world.

Marcello Mastroianni always struck me as a character in search of a movie he had stumbled out of by accident. We used to live on the same street, Marcello and I, and we both frequented the same cafe. It was called Le Mandarin in those days; now Le Mondrian. We were both creatures of habit, always sitting in the exact same spot. We never spoke, not in so many words, but he often silently acknowledged my presence, gratifying me with a glance or a half-smile as he walked past my table. After all, we were often the only customers there. No sooner had the venerable actor been served than a strange performance, straight out of commedia dell’arte, would begin. One of the waiters stood at the entrance, on the lookout for Mastroianni’s partner, film director Anna Maria Tatò. When she finally loomed into view — often accompanied by a retinue of well-heeled Italian friends — the waiter gave a discreet signal to his colleagues, who would whisk away the actor’s glass and ashtray. Another waiter would spray a few squirts of air freshener to ensure that Marcello’s missus did not suspect that he was still a heavy smoker, while yet another produced a fresh cup of coffee to ensure that she did not suspect he was still a heavy drinker. One of Mastroianni’s friends once applauded the garçons’ performance, shouting “Bravo! Bravo!” (in Italian) just as Mrs Tatò walked in, right on cue.

Simon de La Brosse was working as a waiter in Montmartre, when he was discovered by Eric Rohmer, who cast him in Pauline at the Beach (1983). I knew him a little. We attended the same school for a couple of years; lived in the same neighbourhood. It was shortly after he had told me about Rohmer that I noticed how all the girls watched him longingly that time he played volleyball at school. It could have been basketball, come to think of it now, but I am fairly sure that he was sporting similar shorts to those he would wear in Pauline — blue with white stripes down the side. Only they may have been red or orange, and unstriped. Definitely unstriped. He went on to become one of French cinema’s rising hearthrobs in the 80s and early 90s, playing, for instance, alongside Charlotte Gainsbourg in The Little Thief, or Sandrine Bonnaire in The Innocents. Although he was cast in major films by the likes of André Téchiné and Olivier Assayas, it is difficult not to reinterpret Simon’s career in light of how it ended. Here are three examples:

1. In Garçon!, starring Yves Montand, Simon plays the part of a waiter in a brasserie, as though he were doomed to return to his day job. He is frequently on screen, but those appearances are so brief that he is gone by the time you recognise him. To add insult to injury, he does not utter a single word throughout.

2. Simon was given a few lines in Betty Blue. They were not very good ones, however, and the entire scene was cut from the film when it was released in 1986 (although it was reinstated in the 1991 version).

3. One of my favourite clips of Simon is a silent screen test shot at the Cannes Film Festival. The fact that we even know at what time of day filming took place (11.45 am on 16 May 1986) is particularly poignant. Here he makes the most of his theatrical training and miming talents, as well as his immense charm. He reminds me of a matinee idol, or a dashing early-20th century aviator; perhaps one who soared too high, ending up in another dimension. Simon seems to be talking to us from behind a thick glass partition, which renders his words inaudible. His career nose-dived in the 1990s. In 1998 he took his life somewhere else. Sometimes, I fancy I can almost hear him on the other side of the pane.

What seems natural in a movie is precisely what does not come naturally in real life. The on-screen character is usually pure being: she seems to coincide perfectly with herself. The experience of being an off-screen human being, however, is essentially one of non-coincidence. As Giorgio Agamben puts it, “The human being is the being that is lacking to itself and that consists solely in this lack and in the errancy it opens”. You walk out of a western feeling like a cowboy, but the swagger soon wears off, and self-consciousness returns. This self-consciousness is the consciousness of the “gap between me and myself” Fernando Pessoa speaks about. I suspect Simon de La Brosse struggled with the paradox, shared by many actors, of only feeling truly alive when he was not playing his own part. Tom McCarthy reflects upon all this in his first novel, Remainder:

The other thing that struck me as we watched the film was how perfect De Niro was. Every move he made, each gesture was perfect, seamless. Whether it was lighting up a cigarette or opening a fridge door or just walking down the street: he seemed to execute the action perfectly, to live it, to merge with it until he was it and it was him and there was nothing in between.

In real life you can only find yourself by losing yourself, and there is no happy end. This may be what Simon is mouthing through the pane.

At one point in Ben Lerner’s Leaving the Atocha Station, the narrator confesses, “I felt like a character in The Passenger, a movie I had never seen”. Well, I frequently feel like a character in Mauvais Sang, a movie I have never seen (although that did not prevent me from mentioning it in one of my stories). In 1986, when Leos Carax’s film came out, there was a massive student strike in France. We occupied the Sorbonne for the first (and last) time since May 1968, and almost brought the right-wing government to its knees. I remember a couple of girls playing “White Riot” on a little cassette recorder during the occupation, and thinking that this moment was The Clash’s raison d’être. Joe Strummer would have been so proud of us. The voltigeurs — a police motorcycle unit created in the wake of the 1968 student uprising — was deployed in order to transform a peaceful movement (that was largely supported by the general public) into a violent one, thus triggering a cycle of disorder and repression. Behind the driver sat a truncheon-toting thug whose mission was to hit anything that moved. On one occasion, I looked on in disbelief as they beat up a couple of harmless old-age pensioners who were probably walking home after a night out at the pictures.

On another, I narrowly escaped the voltigeurs by hiding under a roadworks hut. When I got home, in the wee hours, I switched on the radio and learned that a fellow student had been killed only a cobblestone’s throw from my hideout. Some of the screams I had heard may have been his. After the strike, a group of us launched a student magazine called Le Temps révolu. We chose the title by opening Zarathustra at random until we found something we liked the sound of. Editorial meetings were held at a Greek student’s flat. He was called Costas, and had fled his homeland in order to escape military service. According to rumours, he had been a kind of Cohn-Bendit figure back in Greece. All in all, we produced two issues, which we sold half-heartedly outside our university. In the first one — by far the best — a girl called Myriam had written an intriguing review of Mauvais Sang — a film which, for me, came to embody the spirit of 86, despite having never seen it. Or perhaps it was for that very reason. Myriam (if that is indeed her name) was one of at least two girlfriends Costas was sleeping with, although not (as far as I know) simultaneously. I have absolutely no idea what the other one was called, but I can vaguely conjure up her tomboyish features. The last time I bumped into Myriam and Costas, they were scrutinising pictures from Down By Law and Stranger Than Paradise outside an arthouse cinema — possibly the same one those pensioners had left before being assaulted by the police. Costas: if you are reading this, I still have your copy of Bourdieu’s Distinction that you lent me almost three decades ago.

I cannot say when I first visited New York. I can only say, for sure, when I visited it again. Again for the first time. That was in August 1981. My immediate impression was akin to the one I had had while watching The Graduate or Jaws: a sense of a homecoming to a place that was alien to me. On every street corner, a feeling of déjà vu. Travelling to this Unreal City from Europe felt like travelling forward into the future (TV on tap! Bars and restaurants open all night!) but also backward into one’s past. We were the first generation to have been brought up in front of the television, suckled on American movies and series. I grimaced at Peter Falk when I spotted him in a Greenwich Village restaurant — to keep up the punk front — but deep down I was very impressed indeed. Initially, we followed the tourist trail, always on the lookout for signs of local punk activity. We caught The Stimulators playing at CBGB’s after seeing an ad in a copy of The Village Voice we read on the ferry back from Liberty Island. Their drummer — a very intense little skinhead called Harley Flanagan, who could not have been older than 14 — filled us in on the New York scene, and gave us a few tips as to where to go, over a game of pinball. If Benjamin and Elaine in The Graduate had produced a son straight away, I reckon he would have looked a lot like this diminutive skinhead. He would have attended boisterous gigs by the Circle Jerks (a Californian band I discovered on that New York trip) where I picture him moshing to “Beverley Hills”:

Beverly Hills, Century city

Everything’s so nice and pretty

All the people look the same

Don’t they know they’re so damn lame.

There is a striking blankness, a radical affectlessness to Benjamin and Mrs Robinson’s demeanour and character; a vacancy to their mating rituals, that hark back to existentialism but point to punk. Even when Benjamin claims to be “taking it easy,” there is an angst-ridden edginess — a white suburban nihilism — to his professed aloofness. The early street and drive-in scenes may be teeming with strategically-placed beatnik hipsters; the attitude, however (in the first part of the movie at least), is pure punk.

Back in New York, we were soon immersed in the burgeoning hardcore scene — slam dancing, the A7 club in the East Village, hanging out with H.R. from the Bad Brains — which embraced us on account of our quaint London accents, as well as our look which pretty much outpunked anyone else in town at the time.

We had decided to leave our cameras at home in order to experience the city fully — to merge with it rather than remain on the outside looking in (or up at the skyscrapers). As a result, we have no record of all the adventures we lived through, all the wonderful characters we met, and our increasingly hazy memories are constantly being rewritten. Paradoxically, there must be dozens of pictures of us knocking about as people kept taking our picture on the street. At first we kept count, but within a few days we were already in the hundreds, so gave up.

It is difficult to express how thrilled I was whenever I discovered an outdoor basketball court that seemed to have come straight out of West Side Story. The more it resembled a film set, the more realistic it felt. A year earlier, I had gone to see that movie almost ten times in the space of a few weeks. Leaving the cinema was an exile. West Side Story inhabited me, and New York felt like I had moved in at last.

We cried on the day we had to go back, and resolved to return soon; for good this time. The plan was to sell hot dogs and be free. Life, however, got in the way.

The second time I visited New York was in 1999. It no longer felt like travelling into the future, and I was unable to find my way back to the past.

I once was an extra in an episode of a French TV series starring a bunch of ropey old luvvies. This must have been around 1982. They were shooting a scene that was supposed to take place in a punk club, so they rounded up a few local punks at the Bains Douches to make it look authentic. All we were meant to do was sit, hang, or dance around. And act punk. I mainly sat, when I was not skulking in some dark (dank?) corner. For some reason, the producers had also hired a handful of young actors dressed in what they believed to be punk attire. In reality, they resembled tabloid caricatures of what some part-time punks may have vaguely looked like down at The Roxy a good five years earlier. By 1982, it was all studded leather jackets and outsize multicoloured mohicans. Nina Childress and Helno, who were both members of Lucrate Milk, really stood out. Nina is now a painter. Helno, who went on to find fame with Les Négresses Vertes, is now a corpse.

The atmosphere soon became so tense that the production team almost called it a day. Each time the punked-up extras were called in for a retake, they were ambushed in an increasingly enthusiastic mosh pit. It felt like smashing The Spectacle. In the end, we were paid (200 francs each if memory serves) and asked to leave. We could not, though, because a gang of skinheads was waiting for us outside. They wanted to smash The Spectacle too, and we were it. I caught the episode, by chance, when it was broadcast a few months later. I believe you can spot my bleached spiky hair on occasion, but overall I had done a pretty good job of remaining invisible.

Someone should compile all the exterior scenes in movies where a “real” passerby turns round to look at the camera, thus shattering the illusion of authenticity. In “The Sign of Three,” which was on television last week, there is a brief sequence during which Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson (Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman) cross the bridge over the lake in St James’s Park. On the left-hand side, a redhead in a skirt suit can be seen walking away from them; from us. She holds a Burberry-style raincoat in one arm, a briefcase in the other, and embodies everything that can never be put into words. I defy anyone — irrespective of gender or sexual preference — to watch this extract without zeroing on her. Naturally, I assumed that she was an extra with a walk-on, or rather walk-away, part, but on second viewing I noticed that she turns round when the camera is sufficiently remote. As she does so, she is subtly pixelated, so that she remains anonymous, and therefore part of the background, the tapestry of London commuter life. What is the status of this lady who is the secret subject of this segment? What is the status of all those passersby who do not pass by as they should? And what is the status of all those who do act as they are expected to — as though a film were not in the process of being shot? “I’m living in this movie, but it doesn’t move me,” as Howard Devoto sang in a Mickey Mouse voice on Buzzcocks’ “Boredom”. Are such unwitting extras — the anonymous people you cannot look up on Wikipedia — truly part of the work (cinema’s effet de réel), or are they merely interlopers? My contention is that they are the element of chance Marcel Duchamp invited into his work, but which only ever turned up unbidden (when the two panels of The Large Glass were accidentally, but artfully, shattered, for instance).

One of the iconic scenes in Lewis Gilbert’s Alfie (1966) sees Gilda (Julia Foster) running through a market and a side-street strewn with urchins. Its sleek lightness of touch vaguely recalls the Nouvelle Vague, but this sentimental working-class tableau is too reminiscent of cinéma vérité to be truly spontaneous. The children, who may well have lived in the Victorian houses that line the street, have clearly been strategically placed; their games choreographed. Just before, as Gilda catches a double decker en route to Alfie’s, three schoolkids can be spotted through the window walking towards a bus stop. They have nothing to do with the film, but are still part of it. Its living part perhaps. Whenever I watch that brief clip, there they are, back in 1966, walking to the bus stop after school. For ever going home.

[This essay was commissioned by Nicholas Rombes, who was Writer in Residence at Necessary Fiction in December 2013-January 2014. It was part of a series of fiction and non-fiction pieces on the theme of “movie writing”.]

The Space Between the Notes

Claude Debussy

Music is the space between the notes.

[Quoted in Jonathan G. Koomey’s Turning Numbers into Knowledge: Mastering the Art of Problem Solving, 2001]

Possibility Never

Søren Kierkegaard, Either/Or

If I were to wish for anything, I should not wish for wealth and power, but for the passionate sense of the potential, for the eye which, ever young and ardent, sees the possible. Pleasure disappoints, possibility never. And what wine is so sparkling, what so fragrant, what so intoxicating, as possibility!

Evanesce Into Pure Gesture

Brian Dillon, “A Poet of Cloth,” Objects in this Mirror: Essays 2014

Beau Brummell is a direct precursor of the dandy Marcel Duchamp. The dandy’s intention is in fact to make the garment — like the artwork — evanesce into pure gesture, to institute something like the “threadbare look” described by Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly in his essay on Brummell and dandyism. In a brief craze, says d’Aurevilly, dandies took to rubbing their clothes with broken glass, till they took on the appearance of lace, became “a mist of cloth,” scarcely existing as clothes.

Keatsian Music

Ben Lerner, “The Actual World,” Frieze 156 (June-August 2013)

… Instead of talking myself out of this (largely indefensible) distinction between the actuality of visual art and the virtuality of the literary, I’ve come to embrace it; I’ve come to think that one of the powers of literature is precisely how it can describe and stage encounters with works of art that can’t or don’t exist, or how it can resituate actual works of art in virtual conditions. Literature can function as a laboratory in which we test responses to unrealized or unrealizable art works, or in which we embed real works in imagined conditions in order to track their effects.

The traditional literary response to a nonverbal work of art is the ekphrastic poem — a poem that uses verbal art to engage a visual one. While the ekphrastic poem is in part judged by its powers of description, the thing it describes can be fiction. The classic example of ekphrasis, for instance — the description of Achilles’s shield in Homer’s The Iliad — is so elaborate as to cease to be realistic; no actual shield could contain all that detail. (This makes sense, since the shield was made by a god.) The verbal, while pretending to give life to the visual, often transcends it: words can describe a shield we can’t actually make, can’t even paint. (Just don’t take a shield made out of words into battle.) Or consider another canonical example of ekphrasis, John Keats’s ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ (1820), wherein we encounter a description of an impossible music prompted by a meditation on a plastic form: ‘Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard / Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on: / Not to the sensual ear, but, more endear’d / Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone.’ My point is that ekphrastic literature is often a virtual form: it describes something that can’t be made given the limitations of the actual world.

For me, at least at the moment, the novel, not the poem, is the privileged form for the kind of virtuality I’m describing. I think of the novel as a fundamentally curatorial form, as a genre that assimilates and arranges and dramatizes encounters with other genres: poetry, criticism and so on….

[T. J.] Clark is rigorously involved with two real canvases, of course, but the novel is a space wherein such an experiment in art writing can take place before the existence of the art itself, where an encounter can be staged between individuals and/or art works that are not or cannot be made actual. Fiction that describes encounters with artificial objects that don’t yet or can’t yet exist is usually called ‘science fiction’ — a prose that attempts to make discernable the shape of an unrealizable technological culture. But we could also organize a genre of ‘speculative fiction’ around virtual arts: Keatsian music; a painting that never dries. Writing is particularly suited to figuring what we can desire or fear but can’t (now) make, especially relative to those arts that depend on seeing.

Banishing the ‘literary’ — the temporal, the representational — from visual art was a major (if unsuccessful) 20th-century critical project. And those artists — like Judd — who moved away from traditional media altogether to real objects and real space further made the kind of virtuality I’m describing the domain of the literary. We’re often told that the figure within the work was replaced with the viewer standing before it. Ejecting the virtual from the object increased the former’s power: now it could reabsorb the object along with is viewer. Literary virtuality became the ghost of the actual, driving certain artists crazy, driving them conceptual. Perhaps we can think of contemporary artists’ increasing interest in literary techniques in part as a desire to reincorporate the power of the virtual back into their work.

So what is the power of the virtual? Michael Clune, a brilliant young literary critic, argues in his book, Writing Against Time (2013), that certain writers ‘invent virtual techniques, imaginary forms for arresting neurobiological time by overcoming the brain’s stubborn boundaries’. This isn’t something literary form can actually accomplish — Keats’s imaginary music can’t be played. Instead, Clune writes, ‘the mode is ekphrastic. These writers create images of more powerful images; they fashion techniques for imagining better techniques.’ ‘Like an airplane designer examining a bird’s wing’, the writer of the virtual ‘studies life to overcome its limits’. Clune is particularly focused on representations of works that defeat time, but we can say more generally that the virtuality of literature allows it to produce images of impracticable techniques — to open a space where the visual artist can desire and think beyond the stubborn boundaries of her materials. Instead of grounding the (often competitive) relationship of verbal and visual art in their similarity — Ut pictura poesis — I think the relationship is most fecund when writers concede the actual to artists.

Vamos Rezagados

The great Spanish novelist Enrique Vila-Matas has posted a link to my 2012 article, “La influencia de la ansiedad,” on his blog.

This End is More Important Than the Other

John Cage, “Indeterminacy,” Silence: Lectures and Writings: 270

One day when I was studying with Schoenberg, he pointed out the eraser on his pencil and said, “This end is more important than the other.”