emiliepierrade does not follow valentinvermot

emiliepierrade does not follow valentinvermot

Oliver Burkeman, “Happiness is a Glass Half Empty,” The Guardian 16 June 2012

In an unremarkable business park outside the city of Ann Arbor, in Michigan, stands a poignant memorial to humanity’s shattered dreams. It doesn’t look like that from the outside, though. Even when you get inside – which members of the public rarely do – it takes a few moments for your eyes to adjust to what you’re seeing. It appears to be a vast and haphazardly organised supermarket; along every aisle, grey metal shelves are crammed with thousands of packages of food and household products. There is something unusually cacophonous about the displays, and soon enough you work out the reason: unlike in a real supermarket, there is only one of each item. And you won’t find many of them in a real supermarket anyway: they are failures, products withdrawn from sale after a few weeks or months, because almost nobody wanted to buy them. In the product-design business, the storehouse — operated by a company called GfK Custom Research North America — has acquired a nickname: the Museum of Failed Products.

This is consumer capitalism’s graveyard — the shadow side to the relentlessly upbeat, success-focused culture of modern marketing. […]

There is a Japanese term, mono no aware, that translates roughly as “the pathos of things”: it captures a kind of bittersweet melancholy at life’s impermanence — that additional beauty imparted to cherry blossoms, say, or human features, as a result of their inevitably fleeting time on Earth.

[…] Behind all of the most popular modern approaches to happiness and success is the simple philosophy of focusing on things going right. But ever since the first philosophers of ancient Greece and Rome, a dissenting perspective has proposed the opposite: that it’s our relentless effort to feel happy, or to achieve certain goals, that is precisely what makes us miserable and sabotages our plans. And that it is our constant quest to eliminate or to ignore the negative — insecurity, uncertainty, failure, sadness — that causes us to feel so insecure, anxious, uncertain or unhappy in the first place.

Yet this conclusion does not have to be depressing. Instead, it points to an alternative approach: a “negative path” to happiness that entails taking a radically different stance towards those things most of us spend our lives trying hard to avoid. This involves learning to enjoy uncertainty, embracing insecurity and becoming familiar with failure. In order to be truly happy, it turns out, we might actually need to be willing to experience more negative emotions — or, at the very least, to stop running quite so hard from them. […]

[Photograph: Kelly K Jones]

Brian Dillon, “Present Future,” Art Review 18 June 2012

[…] ‘The future’, writes Nabokov, ‘is but the obsolete in reverse’.

Isn’t that essentially the would-be paradox that animates a good deal of the future-oriented art of the last decade or two? To the extent, in truth, that it has become a cliché on a par with the popular claim that science-fiction futures are only ever versions of the present in which they are imagined. Contemporary art seems to go further — further back, that is — and assert that the only futures we can conjure today are in fact those that belong to the past: a past in which technology, ideology and avant-garde brio meant that things to come were palpable, vivid, almost present, for much or most of the last century. To speak in terms of tense, the only future that seems to have mattered in the recent past has been the future anterior: what will have been, or more accurately what might have been. […]

Tom Bissell quoted by David L. Ulin, “Critic’s Notebook: Essays Tiptoe Up to Grab Us Unawares,” Los Angeles Times 10 June 2012

To write is to fail, more or less, constantly.

John Cage, Silence; Lectures and Writings (Wesleyan University Press, 1961: 116)

The grand thing about the human mind is that it can turn its own tables and see meaninglessness as ultimate meaning.

John Cage, For the Birds: John Cage in Conversation with Daniel Charles (Marion Boyars, 1981: 116)

There is poetry as soon as we realize that we possess nothing.

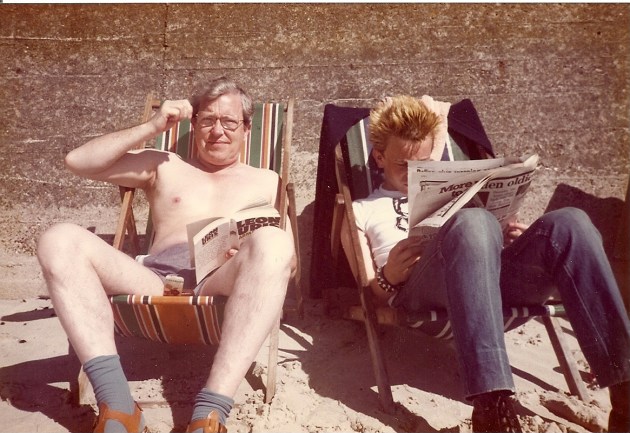

Have just noticed that this picture of me and my stepdad — taken by my mum, in Jersey, back in July 1981 — had been posted on the ISYS (I Saw You Standing) tumblr (This is Me Then, 1 November 2011). He’s rocking the classic socks-and-sandals combo; I’m sporting a punk Charles and Diana T-shirt to “celebrate” the Royal wedding (purchased at the Virgin Megastore on Oxford Street).

Richard Lea, “The Truth About Memory and the Novel,” The Guardian 14 June 2012

[…] The US novelist Francisco Goldman admitted he also called Say Her Name, his portrait of his late wife Aura, a “novel” as a way of avoiding the memoir police, but for him the moments he invented were more than just artistic licence. By making up something that Aura really would have done, or finding exactly the turn of phrase she would have used he was in some sense claiming her back.

[…] In Say Her Name, Goldman examines his late wife’s unpublished fiction, looking for clues to her life in her drafts, her notes. Barthesians may shake their heads at this all-too-human reaction to the death of the author, but perhaps the fact they were still unfinished holds out the hope that these stories contain traces of the author that can still be made out, that the memories which had in some way inspired them can be caught before they have made the transition into fiction.

Bernard Comment, “Bernard Comment: I Write Fiction, to Engrave Time,” The Guardian 14 June 2012

The practice of writing résumés, or the more recent example of Wikipedia, is as chilling as taking an X-ray, when all that remains is a skeleton. In these documents, the hazy tide of a life is reduced to a few dried-out drops — dates, diplomas, geographical locations, professional history – and you can’t find any of that complex, contradictory, muddled pulp that is memory, with its radiant points and its miserable moments, its pride and its shame, its desires and its remorse — not to mention what’s entailed by the Portuguese word “saudade,” that is, nostalgia for what was, but also for what wasn’t and could have been.

Steven Millhauser, BOMB Magazine 83 (spring 2003)

Novels are hungry, monstrous. Their apparent delicacy is deceptive — they want to devour the world. [via.]