Oscar Mardell‘s review of Loren Ipsum in the Irish Times, 7 February 2026, p. 26.

In the 25 December 2025 edition of the TLS, Deborah Levy mentions the time I accompanied her to the Théâtre de la Huchette to see The Bald Soprano. Thankfully, she omits my coughing fit:

“…On a warm evening in October, I made my way with a friend to see The Bald Soprano / La Cantatrice chauve at the Théâtre de la Huchette, where it has been staged since 1957 in its original production, directed by Bataille and designed by Jacques Noël.”

“…My friend and I went to dine afterwards at a local bistrot, not on Rue de la Huchette. A few English tourists arrived and, as if summoned by Ionesco from the other side, began to talk loudly about shooting ducks on a country estate. All the clichés that Sontag loathed in Ionesco’s writing were performatively on display in 2025, as if harvested from an English-language textbook from 1948.”

![]()

“Haunted by the Music.” Review of August Blue by Deborah Levy, The Irish Times, 13 May 2023, p. 26.

A character in Swimming Home (2011), Deborah Levy’s breakthrough title, confides that she only enjoys biographies once the subjects have escaped “from their family, and spend the rest of their life getting over them”. In August Blue, her eighth novel, the author reprises this approach, but flips it round. The family Elsa is striving to get over is the one she never had, hence the question that haunts this book, lending it a spectral quality: how do you escape from the presence of absence?

Elsa M Anderson, the young protagonist, has quite a back story to contend with. Having been abandoned at birth by her mother, this piano prodigy was then “gifted” (authorial pun intended) by her foster parents to Arthur Goldstein, so that she could become a resident pupil at his prestigious music school. Goldstein, a diminutive but flamboyant aesthete, moulds his protégée into a virtuoso performer of international repute. He regards Elsa as his “child muse” rather than simply his child, encouraging her — through the cultivation of her talent — to dwell in a higher abode: “He meant a home in art”. The art of others is what he really meant. Although he cares for her deeply, as becomes apparent in his dying days, Goldstein discouraged Elsa’s “early attempts at composition”, threatened as he was by her ability to “hear something that he did not understand”.

Three weeks prior to the opening scene, this “something” — an “embryonic symphony” — had infiltrated the piano concerto Elsa was interpreting at Vienna’s Golden Hall. Her hands (insured for millions of dollars) “refused to play” the score despite the conductor’s baton-wielding histrionics: for a few minutes, Elsa “ceased to inhabit Rachmaninov’s sadness”, and dared to inhabit her own. She then walked off stage, sabotaging her career but reclaiming her life. As a prelude to this very public breakdown, she had dyed her hair blue, signalling a defiant “separation from [her] DNA”, but also from her mentor, whose “hostage” she had been since the age of six.

After rejecting the “old composition”, Elsa is free to dance to a new tune. An all-pervasive mood of “hyper-alert connections to everything” — not dissimilar to Levy’s adventurous free-associative prose — holds sway as she peregrinates through Athens, Paris, London and Sardinia. Her choice of creation (over interpretation) engenders a proliferation of duplications. Timelines overlap and locales collide in an intricate network of uncanny echoes exemplified by the ants that run along the rim of Elsa’s bath in both her London and Paris flats: “They had found a portal to all my worlds”. The non-binary teenager’s refusal to become their father’s “little me” likewise mirrors the heroine’s quest for identity and autonomy.

Elsa, however, is borne back into the past as she ventures into the future. The repressed returns in various guises, particularly in the shape of a pair of mechanical horses purchased by a young woman in an Athens flea market. These knick-knacks conjure up a recurring childhood memory — that of a piano being pulled by horses across a field — whose significance is slowly revealed to character and reader alike.

Not only does Elsa feel that the mechanical horses have somehow been stolen from her, but she is also convinced that the stranger at the market is in fact her doppelgänger. Although she is in her early 30s, like Elsa, and wears a very similar raincoat, the two women are in no way identical. Yet the protagonist seems to be in telepathic communication with this “psychic double” who, she believes, is stalking her across several countries. Elsa retrieves the hat the woman has forgotten, vowing to hand it back in exchange for the totemic horses.

The extent to which the doppelgänger is merely a figment of her lonely imagination, an idealised version of herself (“Perhaps she was a little more than I was”), or even her polar opposite in some parallel quantum universe remains open to interpretation. With her “attitude and confidence”, she certainly seems to embody the self-composure that the newly emancipated Elsa aspires to: “Perched between her lips was a fat cigar. Glowing at the end. It was a poke at life. A provocation”. At times, this “unlikely double” almost seems to merge with another phantom figure — that of the birth mother.

“My words were smaller than my feelings,” Elsa laments. The novelist’s achievement is to have found words equal to hers. Deborah Levy is now regarded as a grande dame of literature, but she remains as vital as ever, and August Blue is a mistresspiece.

© Andrew Gallix

![]()

This review of Deborah Levy’s The Cost of Living appeared in the Irish Times on 7 April 2018, p. 34:

The Price a Woman Has to Pay For Unmaking a Home

The Cost of Living is the second instalment, and future centrepiece, in Deborah Levy’s autobiographical trilogy. Its pivotal nature becomes apparent when the narrator is loaned a shed of her own, where three books — “including the one you are reading now” — will be conceived. Such foregrounding of the work’s primal scene is no metafictional gimmick, however. It is consonant with Levy’s commitment to looking life in the eye, rather than reflected in the shield of allegory.

“It was there,” she explains, “I would begin to write in the first person, using an I that is close to myself and yet is not myself”. Gazing back at her textual avatar – becoming the reader, as well as the author, of herself – Levy opens up this gap through which she journeys towards the “vague destination” of a “freer life”.

There is a deeply moving, albeit somewhat disquieting, passage, where the nine-year-old Deborah, fresh off the boat from her native South Africa, comes knocking on the door of her middle-aged self in London, and ends up watching Bake Off with the two daughters she will later give birth to. This is a variation on the “flashback in the present” technique that the author frequently deploys to great effect in her fiction, but spectacularly fails to get across to a boardroom full of film executives, in one of the book’s many comic scenes.

Describing this ongoing project as a “living biography” is particularly apposite, not only because the author is alive, kicking and evidently at the height of her creative powers, but also because she eschews nostalgia, firmly convinced that the past is never written in stone. Towards the end of the book, she speaks to her mother for the first time since her passing: “She is listening. I am listening. That makes a change”. She goes on to recount a heart-rending anecdote about a pair of earrings she almost buys her as a gift in a department store, before the unspeakable enormity of death suddenly sinks in at the till.

If Things I Don’t Want to Know (2013) was a response to Orwell’s Why I Write, the emphasis here is on how to write in the wake of two traumatic events which occurred within a year of each other: the break-up of the author’s marriage and her mother’s demise. In the Booker-shortlisted Swimming Home (2011), one of the characters claims to only enjoy biographies once the subjects have escaped “from their family and spend the rest of their life getting over them”. Finding herself in a similar situation, the author now seems to be putting into practice all the themes she has been rehearsing in her works since the 1980s, as though the fiction were a prelude to her vita nova.

As Levy downsizes, her life grows bigger and she feels emboldened and energised by the adventure she has embarked upon despite all the hardship. She has no regrets about swapping her book-lined study for a “starry winter night sky”, now that she writes on a tiny balcony, where she falls asleep fully dressed “like a cowgirl”, in her north London “apartment on the hill”. Other people – including the family from down the road that she borrows for Sunday lunches, the Turkish newsagents and the Welsh octogenarian firebrand who kindly lends her the shed – are a constant source of fascination, but so too are the bees, moths, squirrels and birds she shares the world with: “everything,” she observes, “is connected in the ecology of language and living”. She delights in the practicalities of daily life, even proving a dab hand with a Master Plunger, and when she zips along the road on her electric bicycle, her party dress “flying in the wind”, she finds it difficult not to whoop.

The Cost of Living refers to the price a woman has to pay for unmaking the home she no longer feels at home in. In Levy’s case, this radical act of erasure inaugurates a quest for a new life that is inseparable from the writing of a new narrative. No longer willing to take part in the masquerade of femininity – that “societal hallucination” – she fumbles for a different kind of role to play. At this juncture, all she knows is that it will be a “major [as yet] unwritten female character”. The process of transitioning “from one life to another” also prompts her to reinterpret some of her fondest memories and past attitudes: “Did I mock the dreamer in my mother and then insult her for having no dreams?”

Deborah Levy describes women’s often thankless homemaking enterprise as “an act of immense generosity”. It is also a perfect description of this truly joyous book.

![]()

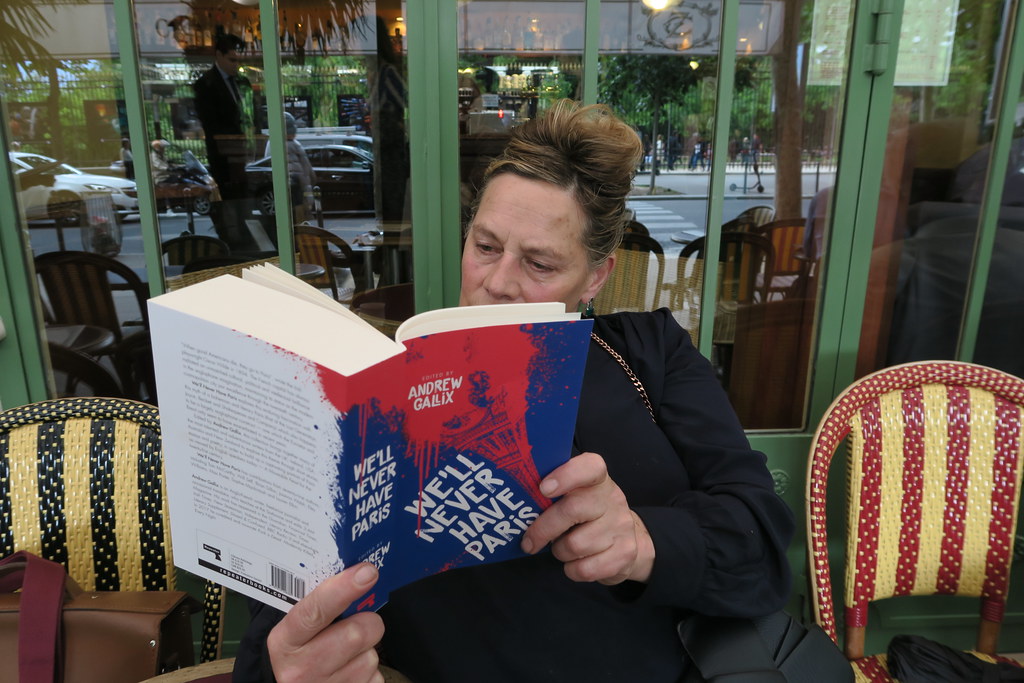

Booker Prize-shortlisted novelist and playwright Deborah Levy has kindly chosen my Punk is Dead: Modernity Killed Every Night as one of her two books of the year.

Levy, Deborah. “Books of the Year.” New Statesman, 17-23 November 2017, p. 41:

I thoroughly enjoyed Punk Is Dead: Modernity Killed Every Night (Zero Books). Edited by Richard Cabut and Andrew Gallix, this anthology of essays, interviews and personal recollections reflects on the ways in which punk was lived and experienced at the time. Gallix flips his finger at those who see nostalgia as an affliction and rightly attempts to promote the fragmented and contested legend of punk to “a summation of all the avant-garde movements of the 20th century … a revolution for everyday life”.

![]()

“Is it easier to surrender to death than life?”

– Deborah Levy, Hot Milk, 2016

![]()

“I’m going to talk about the making of home,” she says. “Women put so much of their energy into creating a home: it’s something I respect deeply; I’ve made a few myself. But there comes a stage, it seems to me, where women don’t feel at home in their home; the very place they’ve created is the place they want to leave. That interests me.”

– Deborah Levy, “A Life In…: Deborah Levy” by Sarah Crown, The Guardian 19 March 2016

![]()

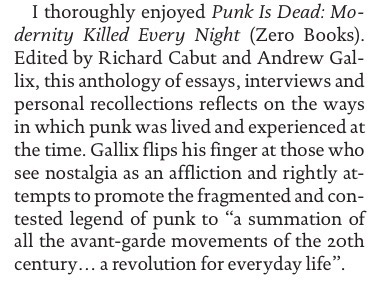

“At Home in the Unheimlich,” my interview with Deborah Levy, appears in the third issue of Gorse. A teaser has been posted online:

Andrew Gallix: I wonder if the discovery of your ‘own voice’ isn’t also due to the adoption of a less theatrical style. Were you more influenced, in the early days, by your playwriting? Many people who discovered you when Swimming Home was shortlisted for the Man Booker, in 2012, had no idea that you had been a successful playwright for many years: did this give you the feeling that you were starting over again as a fiction writer?

Deborah Levy: Yes, I trained as a playwright. Oddly, my two favourite plays written in the 1990s, The B File (an erotic interrogation of five female personas that has been performed all over the world) and Honey Baby: 13 Studies in Exile (performed at La Mama Theatre in Melbourne) are not theatrical at all. Read those plays (Deborah Levy: Plays 1, Methuen) and you will see I’m starting to slip into prose. I can’t begin to convey how hard it was to be a female playwright in the mid-1980s, writing in the way that I did — yes, the whole gender thing — but mostly because I wasn’t writing social realism which was very much in vogue, nor was I writing didactic feminist theatre which was also having a moment at that time. I was much more influenced by Pina Bausch and Heiner Müller than anyone else, though Pinter and Beckett were influences too. Writing for the theatre taught me to embody ideas.

I was giving a reading somewhere recently and a woman came up to me to say she had trained at drama school, and the play she had put on for her graduation show was The B File. I asked her if she remembered her lines, and do you know what, she did! She began to recite them to me, there and then, almost word perfect and with such power. That was the biggest tribute ever, because I knew they had meant something to her. The best actors are incredibly open-minded, shamanistic and playful: I loved those qualities in the rehearsal room.

The prose that is most theatrical is probably my first novel, Beautiful Mutants. Things I Don’t Want To Know is where I pulled open the theatre curtain and switched on the house lights, but obviously that’s not the same thing as saying there’s no artifice in its construction. There is a peculiar relationship between writers and readers — but then all relationships are probably a bit peculiar, aren’t they? For example, I know that Virginia Woolf trusted me when she wrote To the Lighthouse. I was never going to laugh at the seriousness of Lily Briscoe’s struggle and ambition to create a visual masterpiece. There was no nasty little voice saying to me, ooh she’s a bit above herself, isn’t she? I understood the class analysis Woolf made with the angry student Tansley waiting for his toff tutor to talk to him about his dissertation. I understood that domesticated Mrs Ramsay was Woolf’s bid to understand the rituals available to women of her generation, and to have a go at finding something good in them — despite rejecting them herself — via the avatar of Lily Briscoe. I understood that the form of the book was as radical as its content and that Woolf’s vision for her novel was complete. That is what a successful writing-reading relationship should be like. Strangely enough, I’m not the biggest fan of Oscar Wilde’s plays, although I am a big fan of his sensibility. I feel I have a writerly relationship with him, an attachment to his idea that ‘Being natural is simply a pose, and the most irritating pose I know.’

AG: Language can take on an Adamic quality for your characters. Its purpose is to ‘record and classify’ the world, as the narrator of ‘Black Vodka’ puts it. This often leads to a quasi-Oulipian desire to exhaust reality by enumerating its component parts, as in ‘Vienna,’ for instance: ‘She is Vienna. She is Austria. She is a silver teaspoon. She is cream. She is schnapps. She is strudel dusted with icing sugar. She is the sound of polite applause. She is a chandelier,’ and so on until the end of that long, delightful paragraph. The world becomes a kind of litany, as in this example from Swallowing Geography:

In Washington the currency is dollars, the bread yeasted, breakfast waffles and maple syrup, coffee filtered and decaffeinated, golf is being played on slopes of green grass and yellow ribbons hung on taxis. In Baghdad, the currency is dinars, the bread unleavened, breakfast goat’s cheese, coffee flavoured with cardamom, foreheads scented.

Ebele always describes J. K. in this enumerative fashion, much to her annoyance, because ‘That’s what strangers do. When they are in an unfamiliar place they describe it.’ This sends us back to the question with which Swallowing Geography opens: ‘When you feel fear, does it have detail or is it just a force?’ Giving detail to fear is an attempt to master it, to defuse its power. Shortly after, Gregory explains why he collected stamps as a young boy: ‘It was my way of naming places and conquering the world.’ Language, here, is conquest: a means of controlling the world and endowing it with meaning. Jurgen thus views Kitty Finch’s poem as a map that will show him ‘the way to her heart’ (Swimming Home). Is this neurotic, stamp-collecting approach a masculine way of writing?

DL: I am a stamp collector too — the skill is placing one stamp against another. For myself, when the writing is going well, I love the smell of the smoke! Here are some things I dislike in various types of books written by men. I don’t like it when girls and women have no point of view or intelligence or wit or interior life or subjectivity that doesn’t always serve the desires of the male world and its arrangements.

My favourite male writer is Ballard — then Houellebecq, which probably contradicts all of the above, but all his characters are so wrecked that I forgive him. I always buy his books in hardback and now we share the same publisher in France, so wish I could read fluently in French because I could get the book for free. I also love Apollinaire and Nietzsche. I’ve just read Lou Salomé’s gentle and fascinating portrait of Nietzsche translated by Siegfried Mandel. He was in love with Lou Salomé (what a beautiful name) who wisely declined his offer of marriage and wrote a book about him instead. And I admire Burroughs, who was endearingly fragile under that stylish hat. When I’m old and grey and have nothing to do except sit in a hot water spring in Iceland entirely naked (apart from my nose jewel) I think might write about how Burroughs is often misunderstood by the heterosexual men who have been influenced by him. On the other hand I might write a murder mystery set on a cruise ship.

![]()

“I would shoot guns and thrust bayonets through flesh to distract me from myself; I would whip, torture, wrestle, drive racing-cars over cliffs to distract me from myself; jump from helicopters, throw hand grenades to distract me from myself; I would march right left right screaming orders in my throat, obeying orders in my throat, to distract me from myself. I would build muscles I never knew I had, to distract me from myself.”

– Deborah Levy, Beautiful Mutants, 1989: 45