This appeared in Guardian Books on 14 August 2015:

Roland Barthes’ Challenge to Biography

The great critic’s life can certainly be seen in his work, but — as one would expect from the man who pronounced the Author dead — in more complicated ways than we are used to

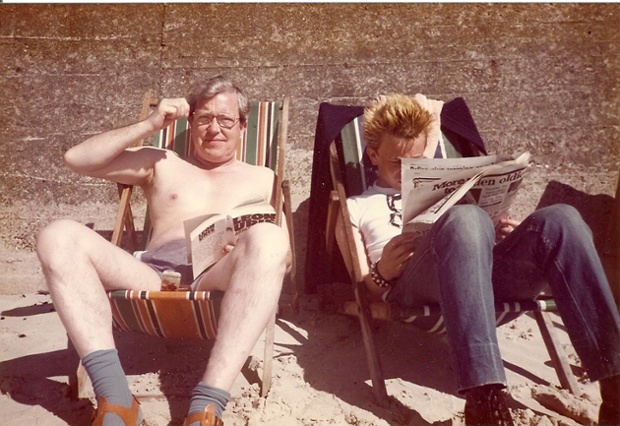

Life in writing … Roland Barthes in 1978. Photograph: Sophie Bassouls/Sygma/Corbis

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a piece on Roland Barthes shall be prefaced by a sarcastic reference to “The Death of the Author“. Especially when the centenary of his birth is commemorated with the publication of a third biography. Tiphaine Samoyault — who had access to a wealth of fresh material — is no ordinary biographer, however. Her premise is that a writer’s life is understood by what it lacks, as much as by the events it encompasses. She highlights the dangers of trying to explain the work through the life, or vice versa, as they are two “heterogeneous realities”. She also wastes no time in reminding us that the death of the writer (following an accident in 1980) is not The Death of the Author (1967).

When Barthes wrote his much-maligned essay, academic criticism in France had barely evolved since the days of Sainte-Beuve. The key to a work of literature was sought, ultimately, in the life — often the private life — of its author. Barthes argued that the latter’s authority was fundamentally undermined by modern fiction. As soon as writing becomes “intransitive” — as soon as language is no longer an instrument, but the very fabric of literature — “the voice loses its origin”: “to write is to reach, through a preexisting impersonality … that point where language alone acts, ‘performs’, and not ‘oneself’”. The “scriptor” — “born simultaneously with his text” and dismissed from it once it is finished — replaces the “Author-God”, whose death implies that a text no longer has an “ultimate meaning”. Every text is “eternally written here and now,” first by the scriptor, and then by the reader, whose creative power Barthes unleashes. (Ironically, this theory could lend itself to a textbook psychological reading, with the author standing in for the absent father.)

The death of the author is that of the Author-God. Barthes does not deny the very existence of the writer. Neither, to be fair, does he deny that biographical elements may come into play during the writing process. When he states that, from a linguistic standpoint, “the author is never more than a man who writes,” he clearly recognises that he or she is never anything less either. When he speaks of literature being an experience of identity loss “beginning with the very identity of the body that writes,” he clearly acknowledges that a body is doing the writing. It is, in fact, the presence of this body which he would increasingly strive to highlight in his intensely personal work.

During a lecture delivered a mere two months before he died, the French theorist disavowed his landmark essay. He shrugs it off as modish structuralist excess, and goes on to confess that he has “sometimes come to prefer reading about the lives of certain writers to reading their works”. Barthes protests too much. There was no “sudden about-face,” simply a shift of emphasis. If in Sade Fourier Loyola (1971) — published only four years after “The Death of the Author” — Barthes mentions an “amicable return of the author,” he hastens to add that this is not a resurrection of the Author-God. First of all, this is the author as he or she is experienced by the reader: “the author who leaves his text and comes into our life”. Secondly, this author has “no unity,” whether psychological or chronological. Finally, this author is primarily a physical presence: “he is not a (civil, moral) person, he is a body”.

The intersection of life and writing was always at the heart of Barthes’s project. Tiphaine Samoyault traces back his interest in self-portraiture to his sanatorium days, the diseased body being his original object of analysis. Susan Sontag shrewdly observes that he started his career by writing about Gide’s journal and ended up reflecting upon his own. He was fascinated by the moment when authors like Stendhal or Proust switched from diary to novel, and seemed to be about to follow suit. His work took a decidedly autobiographical — and indeed literary — turn with the publication of Empire of Signs (1970). This was followed by a memoir in fragments (Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes, 1975) and what Barthes described as an “almost novel” (A Lover’s Discourse, 1977). In the wake of the death of his beloved mother, he declared: “It is the intimate which seeks utterance in me, seeks to make its cry heard, confronting generality, confronting science”.

If Barthes presents biography with a problem, it is not because he is absent from his work, but on the contrary because he is inseparable from it. Etymologically, a text is a piece of cloth, one that, in Barthes’s view, is constantly in the process of being woven. In this making, “the subject unmakes himself, like a spider dissolving in the constructive secretions of its web” (The Pleasure of the Text, 1973). However, it is also through these very secretions that the subject resurfaces, in disseminated form, “like the ashes we strew into the wind after death” (Sade Fourier Loyola, 1971). These ashes are what he called “biographemes”. Barthes also came to identify “life writing” — whereby life becomes the text of the work, à la Proust — as a viable way of voicing the intimate. Beyond that, and even beyond meaning itself, he dreamed of a purely gestural writing that would inscribe “the hand as it writes” — his very desire for writing — into the body of his texts.

In literary biography, the life of an author is traditionally read as leading to the work. After Proust and Barthes, the biographer must treat life and work as two separate entities, which both converge and diverge. Samoyault does everything one expects a conventional biography to do, and more, bringing to life the changing intellectual climate of Barthes’ time, making — to take one iconic example — his silence after the events of May 1968 seem perfectly comprehensible. But with Barthes, it is the work that seems to lead to the life, or at least to biography. If our interest in Barthes’ work draws us to investigate the author, then it is not enough to consult the letters, diary entries and ticket stubs of traditional biography. In the end, our biographical investigations must lead us back to the work itself.