![]()

Ready for pre-order…

![]()

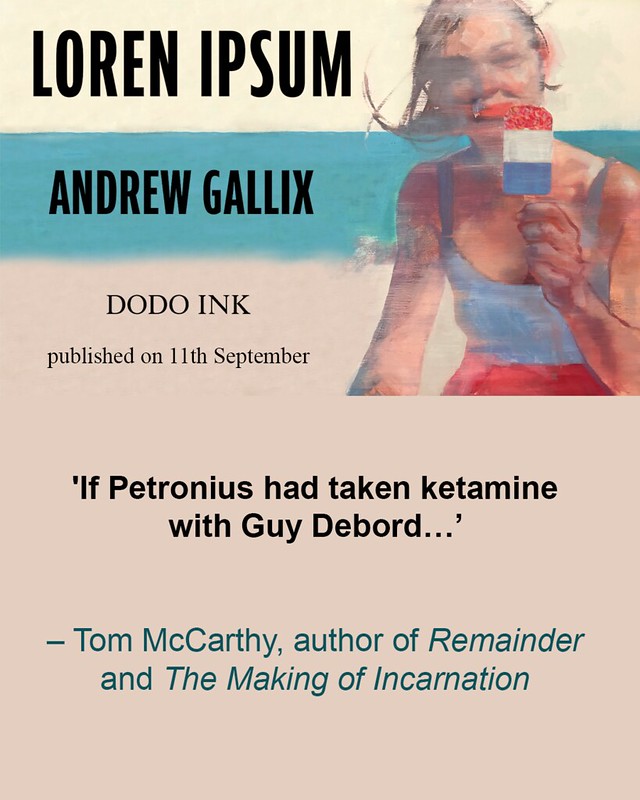

‘If Petronius had taken ketamine with Guy Debord…’

‘Loren Ipsum is like a chemical (or celestial, or necro-feline) phenomenon the very observation of which causes it to radically mutate under your gaze. As you turn the pages, biting satire morphs into tender autobiography, literary theory into crime, and farce into a complex reflection of culture and its place in history’

Tom McCarthy, author of Remainder and The Making of Incarnation

![]()

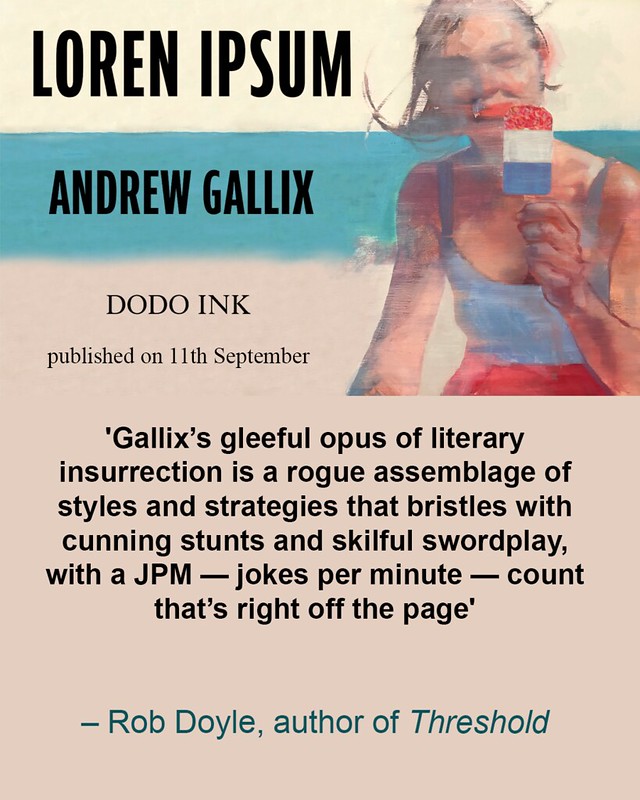

“In Loren Ipsum language itself is up in arms, subverting syntax and blasting holes in meaning left, right, and centre. Gallix’s gleeful opus of literary insurrection is a rogue assemblage of styles and strategies that bristles with cunning stunts, skilful swordplay, and meta-tricksy in-your-endos, with a JPM — jokes per minute — count that’s right off the page”

![]()

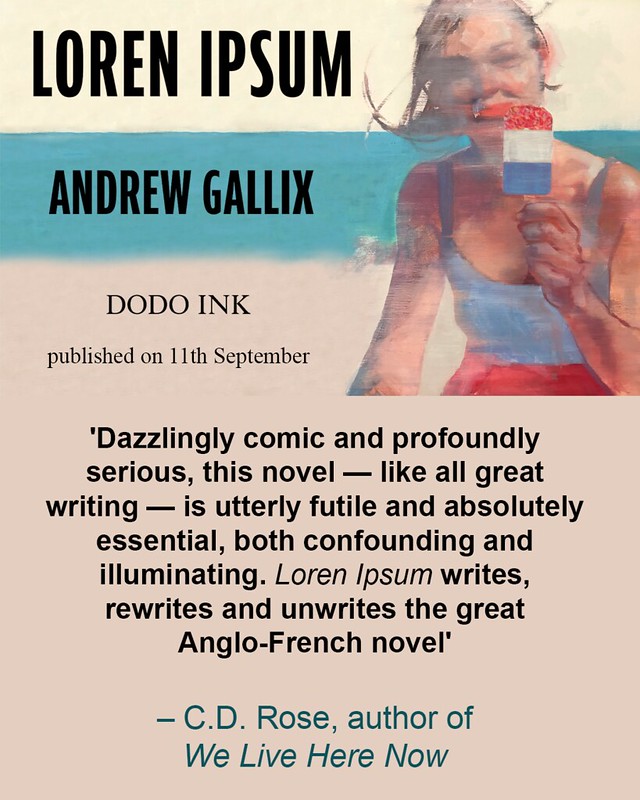

Loren Ipsum is a roman à clef which gleefully scrapes its keys over the surface of the realist novel, turning it inside out and revelling in the carnage it creates. It forms an anti-biography which spills the tea on several lives, teases truth like a saucy flash of knickers, artfully nicks from several sources and spins puns to make sense unspun.

Dazzlingly comic and profoundly serious, this novel — like all great writing — is utterly futile and absolutely essential, both confounding and illuminating. Loren Ipsum writes, rewrites and unwrites the great Anglo-French novel, destroying then re-creating the world with each chapter.