This first appeared in The Guardian‘s Comment is Free section on 23 May 2013. It was reprised in The Guardian Weekly (31 May-6 June 2013, p. 48):

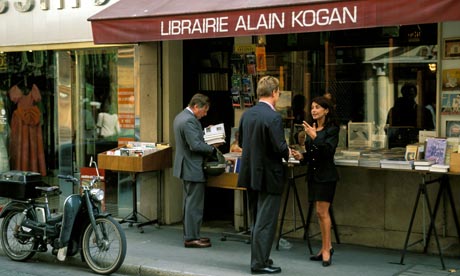

The French Protect Their Language Like the British Protect Their Currency

A row over using English in universities has blown up in France, where language is at the heart of the national identity

‘The nod to Asterix (left, pictured with Obelix) – the diminutive comic-strip hero who punches above his weight thanks to his cunning and occasional swigs of magic potion – is highly significant.’ Photograph: Allstar/Cinetext/United Artist

The front page of Libération, one of France’s leading dailies, was printed entirely in English on Tuesday. “Let’s do it,” ran the banner headline. Sounding like a Nike slogan penned by Cole Porter, it in fact referred to a new bill, which, if passed, would allow some university courses to be taught in English.

Inside the paper (and in French), the editorialists urged their compatriots to “stop behaving like the last representatives of a besieged Gaulish village”. The nod to Asterix — the diminutive comic-strip hero who punches above his weight thanks to his cunning and occasional swigs of magic potion — is highly significant. For decades, France has identified with the plucky denizens of Asterix’s village, the last corner of Gaul to hold out against Roman invasion. This is how the French fancy themselves: besieged but unbowed — a kind of Gallic take on the Blitz spirit.

The reason Uderzo and Goscinny’s books resonated at the time of their publication is that they replayed the myth of French resistance in the context of the cold war. This time around the invaders were no longer German or Roman, but American. Asterix’s first outing (in a long-defunct magazine called Pilote) occurred in 1959, the year Charles de Gaulle became president, and grammarian Max Rat coined the word “franglais“. My contention is that this is not purely coincidental.

France’s identity has long been bound up with its language, more so possibly than anywhere else. This may be due to the fact that French is treated as a top-down affair, policed by the state: an affaire d’état, if you will. Language, for instance, is at the heart of the Organisation Mondiale de la Francophonie, France’s answer to the Commonwealth. The flipside of a state-sponsored language has been a deep-rooted anxiety over linguistic decay and decline. The official custodian of the French tongue — the Académie française — was partly created, back in 1635, to counter pernicious Italian influences.

French nationalism was largely discredited after the second world war, because of the Vichy regime and collaboration. As a result, it often took refuge in cultural — particularly linguistic — concerns. De Gaulle’s inflammatory 1967 speech in Quebec, when he took the linguistic battle into the very heart of enemy territory, speaks volumes. “Long live free Quebec! Long live French Canada! And long live France!” declaimed de Gaulle (en français dans le texte, of course). Quebec was repositioned as a besieged Gaulish village, and French as a symbol of resistance — perhaps even as a surrogate magic potion. For de Gaulle, liberating Quebec meant reversing France’s defeat at the hands of the English in 1763.

My feeling is that France is haunted by its lost American future. Had the US fallen under Gallic domination, French would probably be the world’s lingua franca today. Fears over the decline of French vis-à-vis English are exacerbated by the knowledge that the enemy is also within. Although the linguistic watchdogs regularly come up with alternatives to anglicisms — “mercatique” for “marketing”; “papillon” for “Post-it note” — American expressions are often adopted with far more enthusiasm in France than across the Channel. David Brooks’s portmanteau word bobo (bourgeois bohemian) is more ubiquitous here than in Britain. Even more worrying, perhaps, is the French penchant for unwittingly redefining (“hype” for “hip”) or making up new English expressions (brushing, footing, fooding etc.).

The unregulated flexibility of English probably gives it an extra edge in our ever-shifting digital world. As Susan Sontag once pointed out, French is “a language that tends to break when you bend it”. It is significant that many young French speakers today should suddenly switch to English when writing a mél or courriel (if you’ll pardon my French) to a friend.

So what is all the fuss about right now? The higher education minister, Geneviève Fioraso, wants to amend the 1994 Toubon law so that French universities are allowed to teach a limited number of courses in English (which is already the case in the elite grandes écoles and top private business schools). The main aim of this is to attract foreign students, particularly from rapidly expanding economies such as China, India, or Brazil.

Unfortunately, Fioraso committed an unforgivable faux pas — on a par with Sarkozy’s disparaging comments about the Princess of Cleves — when the idea was first mooted in March. She warned that if teaching in English were not introduced, French research would eventually mean “five Proust specialists sitting around a table”. This led to accusations of philistinism on the part of those who believe that sitting around a table discussing the works of Proust is precisely what being French is all about.

Not surprisingly, reactions have been far more favourable in the scientific community than in literary circles. The Académie française is up in arms over what it sees as “linguistic treason”. Prominent academic and author Antoine Compagnon fears that the measure may lead to dumbing down, since most of these lectures would be spoken in “Globish” rather than the true language of Shakespeare. Bernard Pivot, who used to host a top literary TV programme (and belongs to the Académie), argues that French will become a dead language if it relies on English borrowings to describe the modern world. Claude Hagège, a renowned linguist, concurs, saying that France’s very identity is at stake.

Roland Barthes famously described language as essentially “fascist”, not because it censors but, on the contrary, because it forces us to think and say certain things. The idea that we are spoken by language as much as we speak through it is, I think, an important one here: French offers a different world view from English. Today, the symbol of British sovereignty is an independent currency. In France, it is an independent language, and that is indeed something to be cherished.

Here is a longer, unedited version of the same piece:

On Tuesday, the front page of Libération, one of France’s leading dailies, was printed entirely in English. “Let’s do it,” ran the banner headline. Despite sounding like a Nike slogan penned by Cole Porter, it referred to a new bill, which, if passed, would allow some university courses to be taught in English. Inside (and in French), the editorialists urged their compatriots to “stop behaving like the last representatives of a besieged Gaulish village”. The nod to Asterix — the diminutive comic-strip hero who punches above his weight thanks to his cunning and occasional swigs of magic potion — is highly significant. For decades, France has identified with the plucky denizens of Asterix’s village, the last corner of Gaul to hold out against Roman invasion. This is how the French fancy themselves: besieged but unbowed — a kind of Gallic take on the Dunkirk/Blitz spirit. Part of the resonance of Uderzo and Goscinny’s books is that they replayed the myth of the French resistance in the context of the Cold War. Now, of course, the invaders were no longer German or Roman, but American imperialists who spoke the tongue of perfidious Albion (or at least a variant thereof). Asterix’s first outing (in a long-defunct magazine called Pilote) occurred in 1959, the year de Gaulle became president, and grammarian Max Rat coined the word “franglais”. My contention is that this is not purely coincidental.

France’s identity has long been bound up with its language, more so possibly than anywhere else. This may be due to the fact that French is treated as a top-down affair, policed by the state: an affaire d’état, if you will. Language, for instance, is at the heart of the Organisation Mondiale de la Francophonie, France’s answer to the Commonwealth. The flipside of a state-sponsored language has been a deep-rooted anxiety over linguistic decay and decline. The official custodian of the French tongue — the Académie française — was partly created, back in 1635, in order to counter pernicious Italian influences. The title of Joachim du Bellay’s Defence and Illustration of the French Language (1549) — one of the first concerted efforts to raise French to the level of Latin and Greek — is eloquent: defence takes precedence over illustration.

French nationalism was largely discredited after the Second World War, due to the Vichy regime and collaboration. As a result, it often took refuge in cultural — particularly linguistic — concerns. The defence of the French language would be instrumental in de Gaulle’s attempt to counter Anglo-Saxon domination by embodying a third way between the United States and Soviet Union. The President’s inflammatory 1967 speech in Quebec, when he took the linguistic battle into the very heart of enemy territory, speaks volumes. “Long live free Quebec! Long live French Canada! And long live France!” declaimed de Gaulle (en français dans le texte, of course). Quebec was repositioned as a besieged Gaulish village, and French as a symbol of resistance — perhaps even as a surrogate magic potion. The Canadian PM countered that “Canadians do not need to be liberated. Indeed, many thousands of Canadians gave their lives in two world wars in the liberation of France and other European countries”. The two leaders were talking at cross purposes. For de Gaulle, liberating Quebec meant reversing France’s defeat at the hands of the English in 1763.

My feeling is that France is haunted by its lost American future. Had the United States fallen under Gallic domination, French would probably be the world’s lingua franca today. Fears over the decline of French vis-à-vis English are exacerbated by the knowledge that the enemy is also within. Although the linguistic watchdogs regularly come up with alternatives to anglicisms – “mercatique” for “marketing”; “papillon” for “Post-it note” — American expressions are often adopted with far more enthusiasm in France than across the Channel. David Brooks’s portmanteau word “bobo” (bourgeois bohemian) is ubiquitous over here, but has failed so far to take off in Britain. Even more worrying, perhaps, is the French penchant for unwittingly redefining (“hype” for “hip”) or making up new English expressions (brushing, footing, fooding etc.). None of this is new, of course. Dropping English phrases in conversation was already the last word in chic for the crème de la crème in the days of Proust, and René Etiemble’s famous Parlez-vous franglais ? was published as far back as 1964. The unregulated flexibility of English probably gives it an extra edge in our ever-shifting digital world. As Susan Sontag once pointed out, French is “a language that tends to break when you bend it”. It is significant that many young French speakers today should suddenly switch to English when writing a “mél” or “courriel” (if you’ll pardon my French) to a friend.

So what is all the fuss about right now? Higher Education Minister Geneviève Fioraso wants to amend the 1994 Toubon law (or “loi all good” as it is sometimes called) so that French universities are allowed to teach a limited number of courses in English (which is already the case in the elite grandes écoles and top private business schools). The main aim of this reform is to attract foreign students, particularly from rapidly-expanding economies such as China, India, or Brazil. Unfortunately, Ms Fioraso committed an unforgivable faux pas — on a par with Sarkozy’s disparaging comments about the Princess of Cleves — when the idea was first mooted in March. She warned that if teaching in English were not introduced, French research would eventually mean “five Proust specialists sitting around a table”. This led to accusations of philistinism on the part of those who believe that sitting around a table discussing the works of Proust is precisely what being French is all about.

Not surprisingly, reactions have been far more favourable in the scientific community than in literary circles. The Académie française is up in arms over what it sees as “linguistic treason”. Prominent academic and author Antoine Compagnon fears that the measure may lead to dumbing down, since most of these lectures would be spoken in “Globish” rather than the true language of Shakespeare. Bernard Pivot, who used to host a top literary TV programme (and belongs to the Académie), argues that French will become a dead language if it relies on English borrowings to describe the modern world. Claude Hagège, a renowned linguist, concurs, saying that France’s very identity is at stake.

Roland Barthes famously described language as essentially “fascist”, not because it censors but, on the contrary, because it forces us to think and say certain things. The idea that we are spoken by language as much as we speak through it is, I think, an important one here: French offers a different world view from English. Today, the symbol of British sovereignty is an independent currency. In France, it is an independent language, and that is indeed something to be cherished.

[* In The Guardian Weekly, this article appeared under the following heading: “The French Are Right to Protect their Language: It Runs to the Heart of their Identity and Offers a Different Worldview to English”.]

[Science Fiction novelist China Miéville has criticised the Booker Prize for becoming its own genre. Photograph: Sarah Lee for the Guardian]

[Science Fiction novelist China Miéville has criticised the Booker Prize for becoming its own genre. Photograph: Sarah Lee for the Guardian] [Turn it on again … server outages were undeniably on the rise, but this time there was no website to check. Photograph: Thomas Northcut/Getty Images]

[Turn it on again … server outages were undeniably on the rise, but this time there was no website to check. Photograph: Thomas Northcut/Getty Images]