![]()

Greer, Rob. “Changing the Narrative.” Review of Unwords by Andrew Gallix, The Idler, July-August 2024, pp. 95-96

![]()

Greer, Rob. “Changing the Narrative.” Review of Unwords by Andrew Gallix, The Idler, July-August 2024, pp. 95-96

![]()

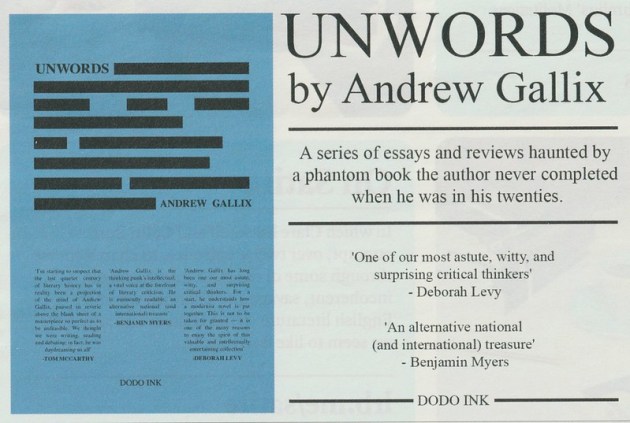

Nesbitt, Huw. “Reading and Writing: Thirty Years of Textual Snapshots.” Review of Unwords by Andrew Gallix, Times Literary Supplement, 14 June 2024, p. 25

Masquerading as a wide-ranging collection of literary essays, Unwords is in fact a hybrid work of critical theory and biography. A reader might object that literature is already brimming with such experiments. Yet few are delivered with Andrew Gallix’s charm.

Originally published in the TLS, the Guardian, the Irish Times and 3:AM Magazine, the literary website Gallix founded in 2000, the essays in this collection are written in crisp newspaper prose, avoiding the preponderant “I” and paragraph-long sentences frequently found in creative non-fiction. At the book’s heart sits the story of Gallix’s writing career. In 1990, he landed a deal with a publisher for a book about a “middling English novelist and playwright (dead)”. Then Gallix blew it, writing an unwieldy, unfinishable Gesamtkunstwerk instead. Undeterred, he took to criticism, opting to sketch a treatise on literature via freelance commissions.

“The best authors … are wary of the consolations of fiction”, Gallix writes in an article on literary realism. “They sense that the hocus-pocus spell cast by storytelling threatens to transform their works into bedtime stories.” He prefers — and draws this collection’s title from — what Samuel Beckett described as the literature of the “unword”: fiction that isn’t just about something but is the thing itself. “The reality of any work of art is its form, and to separate style from substance is to ‘remove the novel from the realm of art'”, he notes in another essay, quoting the nouveau romancier Alain Robbe-Grillet.

To elaborate this thesis, he explores the work of authors often classed as stylists. Naturally there are big names: Jonathan Franzen, Joyce Carol Oates, Deborah Levy, Joshua Cohen. But, Gallix is equally at home with the obscure. “The book’s apparent lack of direction is part of a strategy … to ensure that it does not become another bogus piece of literary fiction”, he remarks of Lars Iyer’s Dogma (2012), a plotless novel about two bungling philosophy professors. “Perhaps what Tunnel Vision really aspires to be is a self-portrait without a self”, he observes of the Irish writer Kevin Breathnach’s autofictional debut (2019).

A sense of provocation permeates Unwords. This is reinforced by tributes to the Parisian punk icon Jacno (“He belongs to a long line of elegantly wasted rock dandies”) and the French-Egyptian postwar novelist Albert Cossery, who wrote only one sentence a day. For Gallix, literature doesn’t exist to be binged, to delight or comfort: novels are real objects requiring reflection, whose language and syntax very often lead us back to the world itself.

Unwords brings together thirty years of reading and literary contemplation. It offers what Roland Barthes termed biographemes, textual snapshots where life and literature are indistinguishable. “Simply put, life writing is writing as a way of life”, Gallix notes. From the disappointment of the book he never published, Unwords’ author has produced something rare: a work of criticism that aspires to the condition of art.

![]()

Aldridge, Jonny. “Haunting and Being Haunted.” Review of Unwords by Andrew Gallix, Writing Stories, 21 May 2024

Most of what I write never lives up to my expectations artistically or commercially and I spent a lot of time (my twenties) haunted by the feeling this was a problem.

But some books change you and Unwords by Andrew Gallix was one of them. It is a litany of reimaginings, reframings of what the novel is. It’s 600 pages of “essays and reviews haunted by a phantom book the author never completed when he was in his twenties”. It’s — a paean to writers who do not feel the need to publish in order to affirm or reaffirm their status qua writers. Writers for whom literature is ‘the locus of a secret that should be preferred to the glory of making books’ (Maurice Blanchot). Writers of works whose potentiality never completely translates into actuality. Writers who believe in the existence of books they have imagined but never composed. Writers whose books keep on writing themselves after completion.

This list (about a third the length of Andrew Gallix’s in full) seems to me far truer than the narrow notion of a book as the discrete thing bought from shelves in shops or shoved hastily through letterboxes by harassed couriers. If not truer, then more palatable, digestible, and easier on the gut. Proper writers bear this out: the 90,000 words binned during drafting (Bernardine Evaristo), the 40-something full rewrites (Claire Keegan), the seven novels written before the ‘debut’ (Richard Milward)… To say writing is a mess is to say: creativity is creative. The problem isn’t my writing, it’s my expectations. My shallow idea of what the novel can be.

Reinventing the novel

Perhaps this is obvious: Unwords is unapologetically esoteric. But its punk intellectual aesthetic is playful, endearing, and thought-provoking. A collection of 20 years of words, it’s also unsettlingly repetitious. Gallix not only circles the same ideas but reuses the exact same quotes, rehashes the same phrases and sentence structures, plagiarises his own opinions. Haunts his own writing. This is the point. It’s the text he should have completed in his twenties. We are, all of us, writing our ur-novel, seeking the ideal of literature that made us want to wade among words in the first place. …

![]()

Macdonald, Rowena. “From Old Analogue to Nervily Digital.” Review of Unwords by Andrew Gallix and No Judgement by Lauren Oyler, The Irish Times, 23 March 2024

Andrew Gallix is an Anglo-French writer who lives in Paris and set up 3:AM Magazine, one of the first online literary magazines, in the year 2000. Unwords is a collection of essays but is also, as he explains, “not the book I wanted to write”.

The book he wanted to write was a work of criticism started in 1990, for which he got a publishing contract, but which remained unfinished because he couldn’t perfect the manuscript to his liking. “I wanted my book to contain not only multitudes, but everything.”

This “phantom book” haunts the pages of Unwords and the theme of unwritten books, unreadable books and books that attempt but fail to contain the whole of experience (as all books are doomed to do) is revisited throughout along with writers who stop writing, writers who “do not feel the need to publish in order to affirm … their status”, “writers who take their time; writers who take their lives … writers who vanish into their writing” or “who vanish into thin air”.

Unwords includes witty, accessible essays on French philosophers (Barthes, Sartre et al), French and English underground culture and the experimental authors that 3:AM has championed, alongside phenomena such as prank pie-throwing, hauntology and spam literature. Towards the end it includes personal pieces on Gallix’s time as a punk in New York, an elegy to lost childhood/Guy the Gorilla and a moving letter to his late mother.

Gallix is at heart a modernist and has little time for middlebrow, well-made novels by careerist “professional” authors. For me the most inspirational character in Unwords is Albert Cossery, the Egyptian-born writer, who died in 2008 aged 94, and who lived in the same Left Bank hotel for 63 years, did not bother to get a day job and instead subsisted on the royalties from his eight novels and followed the same radically lazy daily routine: “Every day, he got up at noon (like his characters), dressed up in his habitual dandified fashion and made his way to the Brasserie Lipp for a spot of lunch. From there, he usually repaired to the Flore or the Deux Magots where he would cast an Olympian eye over the drones passing by. Then it was time for his all-important siesta. Repeat ad infinitum”.

Neither London nor Paris allows writers to be so lackadaisical nowadays. Unwords may not be the Gesamtkunstwerk that Gallix wanted to write but the erudition contained within is remarkable, and yet it has a charming light touch.

So, to Lauren Oyler’s No Judgement. If I came to Gallix warm, as I’m familiar with 3:AM Magazine, I came to Oyler cold, having never heard of her. …

Gallix is a gentle melancholy guide, more analogue, older, European; Oyler is nervily digital, younger, very American in sensibility despite more than a decade in Europe. …

Unwords and No Judgement reveal the world views of two equally clever authors; are you in the mood for encouragement towards intellectual discourse, or confrontation?

![]()

Law, Jackie. Review of Unwords by Andrew Gallix, Bookmunch, 6 March 2014

With every Tom, Dick and Jackie now able to post their thoughts on the books they read online and thereby call themselves a book reviewer, it is good to find someone who knows their stuff and can express opinions well. What we have here is a hefty tome — over 600 pages in length — of book reviews and essays gathered together from a couple of decades of the author’s published critiques and opinions. Andrew Gallix is clearly a literary powerhouse. I may not agree with his summations of some of the books I too have read — The Netanyahus by Joshua Cohen, for example — but I can still appreciate the skill with which these reviews have been written. Gallix excavates seams others may not think to dig down to, his knowledge drawing out comparisons and observations the less widely read may easily miss. Authors, whose work is often more multi-layered than many readers recognise, would likely be gratified by such surgical attention to their words.

Given its size and contents, Unwords is not a book to be read cover to cover as one might a novel. Rather, it is best dipped into, savoured over time in bite sized chunks. It serves as a sort of archive of European literature, a useful reference for anyone with an interest in the oeuvre.

Gallix takes occasional side-swipes at modern publishing habits, showing a marked contempt for popular literary prizes. Nevertheless, reviews included here are overwhelmingly positive — a number of the books featured were written by those he lists in the acknowledgements. He is clearly well connected within the literary world, not surprising when glancing down the list of publications these pieces originally appeared in.

“Some of the essays and reviews that appear in this book have been expanded, rewritten, or updated. Others have not.”

So, as well as book reviews there are essays and the occasional interview. These generally focus on particular authors, offering a glimpse into their mindset and processes. They become characters at the hand of Gallix, their written works a thread in the plot of their lives. There are proliferations of: pen names, a desire for anonymity, the performance of marketing a persona. Fictions created are not confined to their written (or unwritten) works.

The pieces included provide much to ponder on what is considered art, alongside the conceits of creators and those who admire them.

Authors who take the importance of their output so seriously they cannot publish for fear it won’t be good enough are included. Some feel themselves superior in this: “untainted by recognition” (I did wonder how Albert Cossery funded his hotel room and presumably necessary food).

The works of authors under discussion may impress but many of those featured do not come across as decent human beings. There appears to be disdain for the happily ordinary, those not aspiring for inclusion within their circle of influence.

“Platonic writers tend to see their works as imperfect reflections of an unattainable literary ideal. They do not celebrate the birth of a new opus so much as mourn the abortion of all the other versions that could have been.”

In some ways Unwords could have been regarded as a sort of vanity project — Gallix couldn’t finish the novel he planned to write in his twenties so instead pulls together a book from all the short pieces he did complete over the intervening years. This idea should be given short shrift. The impressive quality of the writing alone makes this tome worth perusing. Much of it, while intellectually stimulating, is also highly entertaining.

In ‘Custard Pie in the Sky’ Gallix is having far too much fun playing with the words he uses. Opinions expressed may at times appear highbrow but remain accessible.

I must also mention a couple of the more personal inclusions. ‘Umbilical Words’ is an intensely moving piece written to be read at his mother’s funeral. ‘Phantom Server’, on the near loss of 3:AM Magazine’s archives, is wonderfully engaging.

The final entry, ‘AfterUnword’, is made up entirely of author quotes and references. They may be enough to make any wannabe novelist question the wisdom of their commitment to seeking publication.

Structured in themes, what is provided is a history of the canon that could become essential reading for anyone wishing to understand the context in which European literature exists. The erudite expositions touch on many ideas including: philosophy, nihilism, absurdity. What becomes clear is how much what is written is a compromise of possibilities.

Any Cop?: A book that surprised me with how much of it lingers, how the whole somehow works given its building blocks. Well worth the time of those with an interest in fiction — and the ecosystem within which such fictions exist.

![]()

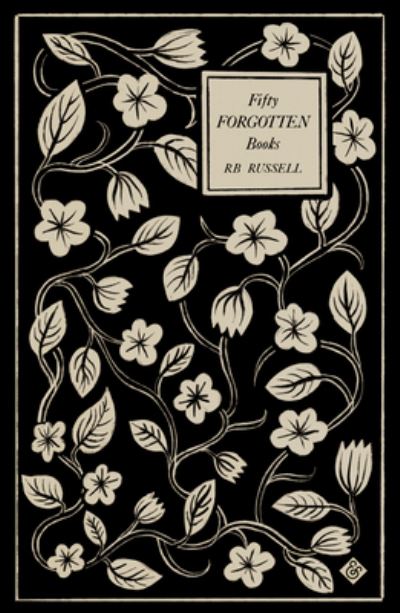

“The Joys of a Dusty Little Gem.” Review of Fifty Forgotten Books by R. B. Russell. The Irish Times, 15 October 2022, p. 27.

Cultural theorists, such as the late Mark Fisher, have argued that loss itself is what we have lost in the digital age. I suspect this goes some way to explaining our fascination with vanished works of art and literature as exemplified by Henri Lefebvre’s The Missing Pieces (2004), Stuart Kelly’s The Book of Lost Books (2005), Christopher Fowler’s Invisible Ink: How 100 Great Authors Disappeared (2012) or Giorgio van Straten’s In Search of Lost Books (2016).

R. B. Russell’s Fifty Forgotten Books is a welcome addition to this list. The author displays a similar passion for unearthing literary curios, but comes at it from a different angle — that of the compulsive collector. He gives us a précis of each title but also, more importantly perhaps, the backstory of the precise copy he owns: which shop he found it in, who recommended it, its price, condition and smell, etc. His first edition of Thomas Tryon’s The Other, for instance, which he happened upon at a jumble sale in Sussex came all the way from a Zetland County library. He treasures the Blaenavon Workmen’s Institute stamps that disfigure David Lindsay’s The Haunted Woman because “they are like ghosts from the book’s past life”.

Throughout this bibliomemoir, which opens in 1981 at the age of 14, Russell haunts — as he makes a point of putting it — second-hand bookshops in search of volumes that are themselves already haunted and will haunt him in turn. Significantly, he describes a “tale of the supernatural set in a bookshop” by Walter de la Mare as “perfect for a reader like [him]”.

The presiding influence over Russell’s bookish life is Arthur Machen (leading him to the work of his niece, Sylvia Townsend Warner), and some of the drug-fuelled antics of the society dedicated to the Welsh author are recounted here in hilarious detail.

The text is interspersed with black-and-white pictures of the book covers and stylish snapshots of Russell and Rosalie Parker, his partner, with whom he set up Tartarus Press. These images belong to an analogue culture that has all but disappeared, along with the “wonderful world of second-hand bookshops” celebrated here. I hope this little gem will be discovered on dusty shelves by future generations of bibliophiles.

![]()

“This Year’s Cult Classic.” Review of Bad Eminence by James Greer. The Irish Times, 16 July 2022, p. 16.

Bad Eminence, American author James Greer’s third novel, is the kind of book you open at your peril. The title alone (a reference to Milton’s Satan) should be warning aplenty, but it is my duty to report that a Latin phrase, planted in the opening pages, leads — once read — to instant possession by the devil. By the same token, I strongly advise you not to cut out and ingest the large dot containing a highly potent hallucinogenic, however much the narrator enjoins you to do so.

Things are already weird enough as it is with the regular intrusion of “sponsored content”, the small black-and-white photographs reminiscent of W.G. Sebald (who is name-checked several times), the recurrence of swans and characters called Temple, not to mention the growing sense of psychosis and gradual dissolution of all ontological certainty.

Vanessa Salomon — the wisecracking narratrix — is a young Franco-American translator, blessed with tremendous “genetic gifts” and a knack for nihilistic aphorisms. Thanks to her reputation for tackling works deemed untranslatable, she is hired by Not Michel Houellebecq to translate his new novel before it is even written. What France’s most famous author really covets, however, is another copy without an original: Vanessa’s celebrity “bitch twin sister”. Or is it?

The novel reaches a metatextual crescendo when the heroine parses a sentence she has just written: “I shut the lid of the laptop and headed back to bed”. She points out that this can only have been typed before or after the event, reflecting her dream of a book that would inhabit “the spaces between the binary code of our existence”. “Everything,” she declares, in what amounts to a manifesto, “is in the process either of becoming or unbecoming, and it is the task of the artist not to make something new but to make something present”.

Once the rollicking narrative has caught up with itself, the novel implodes in real-time. It becomes increasingly obvious that transgressive, S&M fantasies from the Robbe-Grillet book Vanessa was translating at the beginning have been contaminating the rest of her life, and that her world is now awash with simulacra and doppelgängers.

Hilarious, exhilarating and mind-blowing, Bad Eminence is this year’s cult classic.

![]()

Here is my review of Michel Butor’s Selected Essays, Times Literary Supplement, 8 July 2022, p. 25.

Michel Butor has never received anywhere near the level of critical attention in the English-speaking world accorded to his fellow experimenters with the nouveau roman, Alain Robbe-Grillet and Nathalie Sarraute. His third novel, La Modification, is regarded as a modern classic in his native France, where it won the prestigious Prix Renaudot in 1957 and is regularly chosen as a set text at schools and universities. Even in France, however, few appreciate the full scope of Butor’s oeuvre, which encompasses countless poems, art and literary criticism, travel writing, translations and a libretto, not to mention more than a thousand artist’s books. It is to be hoped that the publication of his Selected Essays, carefully curated by Richard Skinner and elegantly translated by Mathilde Merouani, will kindle greater interest in the work of a true polymath, whose questing spirit — unlike that of some of his fellow nouveaux romanciers — never departed him.

Five of the eight essays compiled here, one of which is actually a 1962 interview with Tel Quel magazine, appear in English for the first time. They all deal with various aspects of the novel, which Butor regarded as the greatest of all literary forms. For him it was, at least initially, a way of overcoming a “personal problem”, enabling him to reconcile the poetry he was then writing at home with the philosophy he was studying at university.

This slim volume hinges on the notion that no account of human behaviour is truly complete without the inclusion of the imaginative and oneiric. Much of reality is apprehended through narratives (such as newspapers or history books) that exist on the “ever unstable border between fact and fiction”. Butor’s grand claim — that the novel is “the laboratory of the narrative”, where the way the world is experienced can be explored and, ultimately, transformed — is argued here most persuasively.

Butor makes light work of heavy themes, eschewing dogma and jargon despite the essays’ phenomenological tenor, in stark contrast with many of his contemporaries. Whether he is analyzing how a fictive locale may reconfigure the space in which a book is read, contending that travelling is the dominant theme of all literature or excavating old objects in the work of Balzac, his often exhilarating insights continue to come across as though he were charting terra incognita.

Behind this ever-inquisitive mind, there is a sense of a growing impatience with the constraints of the novel, even in its experimental mode. In the book’s concluding interview Butor discusses his failure to bridge the gap between poetry and philosophy, which may explain why he did not publish any novels after 1960. (He died in 2016.) After 1960 his fascination with the intersection between writing and the arts would take him beyond the confines of fiction into experiments with hybrid works and the book as object.

![]()

Here is my review of The Making of Incarnation by Tom McCarthy. The Irish Times, 2 October 2021, p. 15:

Tom McCarthy’s fifth and arguably most ambitious novel brings to mind Theodor Adorno’s definition of art as “magic delivered from the lie of being truth”. The Making of Incarnation is about bodies in space — outer space in the case of the sci-fi blockbuster (Incarnation) that serves as both armature and mise en abyme. Here, the lie of being truth (which another character describes as “[n]aturalist bullshit”) must be perpetuated at all costs.

Ben Briar is flown in from the United States as part of a shadowy project called Degree Zero (a nod to Roland Barthes and his reality effect) to ensure that the film’s script, however fanciful, complies with the basic laws of physics. Herzberg, the art director, expends a great deal of energy convincing this “Realism Tsar” that the inclusion of mundane objects in the unlikeliest of set-ups can effectively “counteract the defamiliarisation”. Much is subsequently made of the CGI rendering of a fork (“your basic IKEA Livnära”) that recurs — comically as well as cosmically — throughout the climactic disintegration of the spacecraft.

Given that Briar works for a consultancy called Two Cultures (vide C. P. Snow), it is hardly surprising that he should view physics as a creative endeavour — “a plunge into the farthest-flung reaches of the imagination”. The unfolding of the plot, as the shoot progresses, is interspersed with complex descriptions of the wind tunnels and motion-capture techniques deployed behind the scenes. These are so meticulously detailed that they take on a hypnotic, almost hallucinatory, quality.

Kinesis moves in mysterious ways: at every corner, the scientific turns out to be underpinned by the poetic — or even the messianic. Pantaray Motion Systems is not only the slightly sinister corporate behemoth providing the cutting-edge technology without which there would be no movie; it also has “a heroic status tinged with traces of the mystical”.

Anthony Garnett, its founder, recalls once considering Norbert Wiener (the originator of cybernetics) as “prophet, messiah and apostle”. There was something in his vision that he thought “he’d left behind with Aeschylus, Catullus, Sappho: a condition best denoted by the old, unscientific label poetry”.

Garnett’s colleague Pilkington — referred to, behind his back, as the “Ancient Mariner” — senses that all machines are “stand-ins for some ultimate machine we’ll never build but nonetheless can’t stop ourselves from trying to”. Tasked with orchestrating an experimental plane crash, he goes looking for the “ur-disaster” — the “totality that hovers above every partial iteration”.

Monica Dean, who is conducting research into Lillian Gilbreth, discovers that the pioneer of factory-floor ergonomics had come to entertain “the possibility of some ‘higher’ or ‘absolute’ movement . . . derived from no source other than itself”. The novel is teeming with such intimations of preordained patterns or underlying algorithms.

In this quest for perfection, the human body is ultimately an obstacle. We are reminded that the French scientist Marey sought to infuse his compatriots with the “energy and dynamism of the locomotive” and that Taylorism was seen by some in the Soviet Union as an opportunity to liberate the worker from “the shackles of his very body”. This rejection of incarnation is (paradoxically) embodied by the film’s high romantic denouement: the two lovers, whose union is impossible, bow out in a blaze of glory, expecting to coincide with themselves — and everything — at the instant of their deaths.

The novel, however, does not end with the blinding light of revelation, but a “blackness neither rays nor traces penetrate”. Besides, there is an error in the code behind the film’s final frame — an invisible blemish only the technician is aware of. It recalls Pilkington’s secret that he alone was responsible for the failure of Project Albatross, a minute miscalculation having led the plane to vanish instead of crashing. He imagines the lost aircraft occupying “an aporia, blind alley, cubby-hole or nook”.

This instant of its disappearance, “cut out from the flow of time” — for ever suspended, deferred — is akin to the sense of dislocation that several characters experience: the feeling of being in two locations at once “without really being in either”; of experiencing the present and the past simultaneously while being at one remove from both.

Is not this liminality the very space of fiction, squatted by the two addicts, who reappear right at the end, lost in their pipe dreams and inevitably conjuring up Beckett’s Vladimir and Estragon?

The answer, no doubt, is to be found in Lillian Gilbreth’s Box 808 — the one that allegedly “changes everything”, that may “chisel a Northwest Passage through a stretch of the hitherto theoretical-physically impossible”. The one that is missing, of course, and that everyone — from the protagonist, Pantaray’s Dr Mark Phocan, to the secret services — is looking for.

The truth is out there: Tom McCarthy has worked his magic once again.