![]()

Jude Cook. “Vanity Fair.” Review of Loren Ipsum by Andrew Gallix, The Guardian, 15 November 2025:

![]()

Jude Cook. “Vanity Fair.” Review of Loren Ipsum by Andrew Gallix, The Guardian, 15 November 2025.

A brilliant satire on the modern literary scene. Full of word games, in-jokes and grisly murders, this debut pours gleeful scorn on the pretensions of contemporary literary life

Freud would have had a lot to say about a novel in which the central premise is writers being murdered. A manifestation of a repressed desire to eliminate rival literary talent? A clear case of the death drive? Either way, there’s some twisted business going on in Andrew Gallix’s chronically funny debut novel, Loren Ipsum.

The morbid if intriguing premise quickly becomes secondary to an insouciant satire on the vanity fair of present-day literary culture. Not since Paul Ewen’s How to Be a Public Author has so much gleeful scorn for pretentious authors, critics and scenesters been poured on to the page. Taking its title from the placeholder text used while preparing a book for print, the novel features an eponymous protagonist, a journalist resident in Paris, who is researching a monograph on the reclusive English author Adam Wandle. Loren Ipsum somehow manages to be both the book’s moral centre and a shapeshifting cipher for everything that’s wrong with contemporary literary life. With “a heart of frosted glass”, she is “all blurred features and radio static”. Her own first novel, Fifty Shades of Grey Matter, was published by Galley Beggar in 2019. Her favourite bookshop is Shakespeare and Company (“she had all their totes”), and her best party frock is “part Mondrian, part Battenberg”. The knowing list of Loren’s favourite things is peak Bougie London Literary Woman and wickedly spot-on. It’s that kind of book. By the end, you can’t see the modernism for all the posts fencing it in.

As the death toll of Paris’s resident scribes rises, an obscure terrorist group claims responsibility, though their motives are unclear. Happily, the location moves to Antibes, where the carnivalesque action can continue. When Loren joins a literary party on a yacht, there’s a clear nod to Fellini’s 8½, with its melancholy cavalcade of posturing parvenus. Marcello Mastroianni himself makes a cameo later in a passage devoted to Le Tournon, the Parisian cafe where Joseph Roth drank himself to death and where Wandle goes to hide and write his ponderous prose.

Between these set-pieces there are whole chapters devoted to band names (“The Old Duffers, Omnishambles, The Opening Gambits”), and a heterogeneous cast of the great and the good: “Guy Debord in hot pursuit of a statuesque demi-mondaine modelling a lampshade hat … Gilles Deleuze doing the twist to Martha and the Muffins.” There are walk-ons from Andrew Wylie, Roland Barthes and Richard Hell, as well as Gallix’s own publisher, the author Sam Mills. There’s also the running gag of punning chapter titles: What We Talk About When We Talk About Talk; Quiet Days in Noisy; and my favourite, The Man Without Quality Streets. While some of the in-jokes overreach (“the cool clinking of the Žižek-shaped ice cubes”), others hit the spot with laser-guided accuracy. For instance, the moment when the immaculately named Sostène Zanzibar, “who had always tried and failed to convey the inadequacy of words with words”, comes up with the concept of a novel printed in disappearing ink.

Towards the end, the book takes a darker turn: “Shocking footage of a sensitivity reader, who had been tarred and feathered and then shackled to the railings on Mecklenburgh Square, was broadcast.” Then there’s the fate of the English writer Patrick Berkman, who moves to Montreuil but soon finds the banlieue population makes him feel he doesn’t belong, “just as they had been made to feel they did not belong in France”. He’s later found dismembered, his “puny body” partly devoured. Here, Gallix reinforces the notion that comedy is the best place to say something serious; in this instance, about France’s alienation of migrant communities. This is also evident in his unstoppable puns and word games. With their subversive, rebarbative edge, they stay just the right side of clever-clever.

Teeming with literary and pop cultural allusions and antic wordplay, Loren Ipsum ultimately stages a conversation about the uses, and possible uselessness, of literature. It has a nimble wit and a punk rock attitude that is wholly addictive. Destined, as they say, to become a cult classic.

![]()

My official portrait of Sam Mills features on the dust jacket (back flap) of The Watermark, and features in reviews that appeared in The Guardian and Irish Times. Details below.

Litt, Toby. ‘A Time-Travelling Romp.’ Review of The Watermark by Sam Mills, The Guardian, 28 August 2024 (website).

Boyne, John. ‘A Welcome Slice of Eccentricity.’ Review of The Watermark by Sam Mills, The Irish Times, 24 August 2024, p. 27 (Ticket supplement).

Mills, Sam. The Watermark, Granta Books, 2024 (publication date: 1 August 2024).

![]()

My tribute to the late Marc Zermati in the Guardian, 17 June 2020:

Marc Zermati: Farewell to the ‘Hippest Man in Paris’

Zermati, who has died aged 74, was an anglophile dandy whose label Skydog crash-landed rock’n’roll into conservative France

Marc Zermati with the Clash’s Joe Strummer. Photograph by Catherine Faux (Dalle/Avalon.red)

Marc Zermati, who died of a heart attack on Saturday at the age of 74, was a true underground legend: a national treasure France had never heard of and probably did not deserve. Rock Is My Life — the title of a 2008 exhibition celebrating his career on the radical fringes of the music business — would serve as a fitting epitaph.

Skydog, which Zermati co-created with Pieter Meulenbrock in 1972, was the first modern indie label, directly inspiring the launch of Chiswick and Stiff in England — its most successful release was the Stooges’ Metallic KO in 1976. As a promoter Zermati organised the world’s first punk festival, at Mont-de-Marsan, and introduced bands such as the Clash to a French audience. His heroin addiction and wheeler-dealing landed him on the wrong side of the law, and in latter years his curmudgeonly rightwing views alienated many people. But as one of the earliest champions of punk his importance in rock history cannot be overstated; if cut, he would have bled vinyl.

Zermati was born into a family of Sepharadi Jews in Algiers. Growing up against the bloody background of the war of independence, he took refuge in rock’n’roll records imported from the US, which were more readily available — as he often boasted — than in metropolitan France.

Like so many other pieds-noirs (the name given to people of European origin born in Algeria under French rule) the family fled to la métropole in 1962, when the country gained independence. Zermati would always entertain a conflicted relationship with his new homeland, which he deemed backward-looking and inimical to youth culture. Lest we forget, the 1968 student uprising was sparked off by a protest against single-sex halls of residence at Nanterre — France, at the time, was not all nouvelle vague flair and post-structuralists zooming around in sleek Citröens.

It was in fact often very conservative — socially and culturally — and pop music from the US or the UK was frequently met with xenophobic contempt. In interviews, Zermati recalled how the police would constantly harass, and sometimes even arrest him on account of his long hair, and how he would escape to London, where he felt free, as often as possible. In recent years he bemoaned the “Toubon law”, introduced in 1996 to compel radio stations to play at least 40% francophone songs, singling it out as yet another instance of Gallic insularity — further proof that France and authentic rock music were incompatible.

It was not all bad, though. He joined the ranks of the fabled Bande du Drugstore, fashion-conscious members of Paris’s jeunesse dorée who hung out on the Champs-Elysées and were notorious for their hard partying (referenced by Jacques Dutronc on his 1966 hit “Les Play Boys”). These minets, as they were mockingly called, had a great deal of influence on the mod look across the Channel. This week, journalist Nick Kent wrote on his Facebook page that when he first met Zermati, in 1972 (when the New York Dolls were in town with their future manager, Malcolm McLaren), he was the “hippest man in Paris bar none”. Along with Yves Adrien, Patrick Eudeline, Alain Pacadis and a few others, Zermati — whose idea it was to dress the Flamin’ Groovies in sharp Fab Four suits — belonged to a typically French line of anglophile dandies, who would go on to shape the punk and post-punk years.

In the mid-60s Zermati worked in an art gallery in Saint-Germain-des-Prés where he rubbed shoulders with Joan Miró and Henri Michaux, and befriended Max Ernst — the German surrealist encouraged him to explore the burgeoning American counterculture. His first taste of LSD (in Ibiza, where he stayed for a year) was a turning point in his life, and he always claimed to be able to tell people who had experienced its mind-expanding properties from those who had not, however cool they attempted to appear. L’Open Market, the record emporium he opened in 1972 was originally a head shop, where people congregated to peruse the international underground press and smoke dope. The records on sale were few but carefully selected, and it was this loving curation that outlined a rival tradition, bypassing the progressive cul-de-sac and leading straight to punk. Kids who came in asking for the latest Yes or Genesis were shown the door unceremoniously. Lester Bangs, Lenny Kaye, Jon Savage, Chrissie Hynde, Malcolm McLaren and all the local punks-to-be ranked among the customers. Nico could often be found cooking in the apartment above the shop, while bands such as Asphalt Jungle would be rehearsing in the basement.

Zermati’s taste in music, as well as clothes, was always impeccable. The first release on his label was a wild jam session between Jim Morrison, Johnny Winter and Jimi Hendrix (whom he had met in London and venerated), followed by the Flamin’ Groovies’ legendary Grease EP. You would be hard pressed to start on a higher note. As early as 1974, he set up the first independent distribution network in partnership with Larry Debay; alongside the two Mont-de-Marsan festivals, he organised three nocturnal punk gigs at Paris’s Palais des Glaces in April 1977, with an unbeatable lineup featuring the Clash, the Damned, Generation X, the Jam, the Stranglers, Stinky Toys and the Police (still with their French guitarist, Henry Padovani). At one stage in the 80s, he even became the Clash’s de facto manager.

Following a spell in prison, he co-launched another label, Underdog, and went on to promote gigs in Japan (where he took Johnny Thunders). His greatest achievement, however, will always be transforming Paris, for a few short years in the run-up to punk, into what felt like the capital city of the rock world.

![]()

I have written a piece in homage to the late Marc Zermati for the Guardian. Great photo by Catherine Faux of Zermati with Joe Strummer in Paris back in 1981.

Marc Zermati, who died of a heart attack on Saturday at the age of 74, was a true underground legend: a national treasure France had never heard of and probably did not deserve. Rock Is My Life — the title of a 2008 exhibition celebrating his career on the radical fringes of the music business — would serve as a fitting epitaph. . . . [A]s one of the earliest champions of punk his importance in rock history cannot be overstated; if cut, he would have bled vinyl…

![]()

Ashford, James. “What is Hauntology?” The Week, 31 October 2019:

[…] And away from politics, “at its most basic level, it ties in with the popularity of faux-vintage photography, abandoned spaces and TV series like Life on Mars”, said writer and academic Andrew Gallix in The Guardian in 2011.

“When you come to think of it, all forms of representation are ghostly,” he added. “Works of art are haunted, not only by the ideal forms of which they are imperfect instantiations, but also by what escapes representation.”

![]()

George Shaw, “Anarchy in Coventry: George Shaw’s Greatest Hits” by Tim Jonze. The Guardian, 13 February 2019.

“In a sense, I’m painting my own departure — to keep going, until the final painting is empty, and you’re no longer casting any shadow on it.” He muses on this for a while. “That’s when you paint the greatest painting of your life. But the fact is, you’ll never be around to paint it.”

![]()

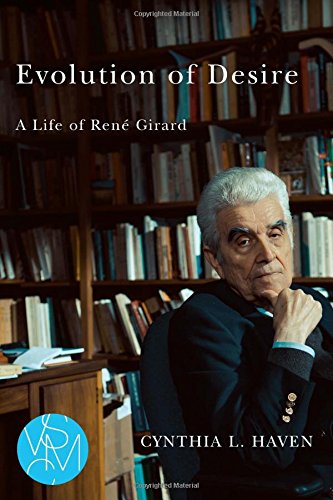

Haven, Cynthia. “’The Genius to Glue Them Together: On René Girard and His Ideas.” Los Angeles Review of Books, 25 March 2018.

Deceit, Desire, and the Novel already bears Girard’s signature writing style — formal yet engaging and approachable, erudite, incisive, and masterful — it’s the book that would make his reputation. I found the book rather addictive, though Library Journal called it “a highly complex critique of the structure of the novel,” and added a warning: “As may be expected, the interpretations are highly psychological, the argument philosophical, and the intellectual footwork, dazzling; but for the reader, the going is slow, and conviction, grudging.”

For many, however, it was a revelation. “You can always trust a Frenchman to view the world as a ménage à trois,” wrote Andrew Gallix in the Guardian, describing Girard’s theory of mediated desire. “Discovering Deceit, Desire and the Novel is like putting on a pair of glasses and seeing the world come into focus. At its heart is an idea so simple, and yet so fundamental, that it seems incredible that no one had articulated it before.”