Full Stop magazine interviewed me as part of their “Pathos” series, examining “the consequences of pursuing writing as a vocation”.

“Pathos: Andrew Gallix,” Full Stop 16 January 2013

Last winter, Full Stop introduced “The Situation in American Writing,” a questionnaire adapted from The Partisan Review that asked questions about literature’s responsibility to address seismic changes in culture, the publishing industry, and the political and geopolitical landscape. That questionnaire, which featured responses from Marilynne Robinson, George Saunders, Victor LaValle, T.C. Boyle, Dana Spiotta, and dozens of other writers was illustrative of the concerns and preoccupations that writers carry with them when practicing their craft.

This year we are interested in the situation of writers, rather than writing, in the subjective experience of writing fiction (or in this case, memoir), rather than fiction’s responsibilities to respond to a rapidly changing world. To this end we are interested in examining the trying intellectual, creative, and emotional labor that is often unacknowledged or effaced in the public presentation of writing. What we’re interested in, to put it another way, is pathos.

This year, we’ve crafted a questionnaire asking writers about the effect writing has had on their physical, emotional, and economic health; on the idea of poverty being a precondition for writing well; on what makes writing truthful to one’s self and to readers. Ultimately, we are interested in the consequences of pursuing writing as a vocation.

Andrew Gallix is the Editor-in-Chief of the consistently great 3:AM Magazine which features a motto that is the envy of Full Stop: ”Whatever it is, we’re against it.” He also teaches at the Sorbonne, writes for The Guardian, and is currently working on a novel, as well as a collection of reviews of impossible books in collaboration with David Winters.

How has your decision to write affected your health? Has it had negative effects on your personal life?

The great Polish writer Witold Gombrowicz said, “One cannot be nothingness all week and then suddenly expect to exist on Sunday.” It’s equally difficult to have a day job and be “nothingness” in the evening — especially if you’re trying to juggle a family life at the same time. Things must be much easier when you can write for a living. I’m pretty sure writing contributed to my divorce, for instance!

There is long tradition that links the craft of writing with poverty. Do you think that’s appropriate? Does poverty feel like the most appropriate condition for your practice as a writer?

No. The authors I know who insist upon writing for a living, although their work is resolutely uncommercial, end up, paradoxically, being obsessed with financial matters. Every single word they write must be counted, and accounted for; turned into money to pay the bills. Don’t get me wrong: writers should be paid, but you can’t force people to buy books, let alone read them. Those lucky, or cunning enough, to find a wide audience don’t usually stop writing, all of a sudden, because they’re raking it in. Some of the most interesting writers today come from very privileged backgrounds. Others don’t, and if their books fail to sell in sufficient quantities, they usually have to supplement their incomes through grants, teaching, journalism, or jobs in publishing. The creative writing industry is, in part, a means of subsidising writers’ careers.

The question of the cost of letters (to refer to the title of a book on this subject published by Waterstone’s in 1998) is an important one, because it reflects the evolution of literature itself. When literature was essentially an aristocratic pursuit — for people who had both time and money — this question was immaterial. It only really arises with the spread of literacy and the emergence of writers who didn’t hail from the ranks of the idle rich. The Waterstone’s book I mentioned — How Much Do You Think a Writer Needs to Live on?: The Cost of Letters (edited by Andrew Holgate and Honor Wilson-Fletcher) — was inspired by a survey of literary living standards carried out by Cyril Connolly fifty years earlier. When it was published by Horizon, in 1948, British society was being radically transformed through mass education and the Welfare State. Connolly’s survey contained the following questions:

How much do you think a writer needs to live on?

Do you think a serious writer can earn this sum by his writing and if so, how?

If not, what do you think is a suitable second occupation for him?

Do you think literature suffers from the diversion of a writer’s energy into other employments or is enriched by it?

Do you think the state or any other institution should do more for writers?

Are you satisfied with your own solution of the problem and have you any specific advice to give young people who wish to earn their living by writing?

The main question (which wasn’t addressed because it went without saying at the time) is, of course, that of the definition of a “serious writer” — one who may be worthy of being subsidised in the absence of commercial success. Who decides who is a “serious writer” in the first place? Is it the writer him/herself? His/her peers? Academia? The media? The reading public? The state? I’ve always been a little dubious about the romantic image of the impoverished, tortured genius scribbling away in his, or indeed her, dingy garret, but it does reflect a very real process of privatisation of the writing profession.

Walter Benjamin famously described the “birthplace of the novel” — and hence that of modern literature — as “the solitary individual”: an individual cut off from tradition, who, unlike the writers of antiquity, could no longer claim to be the mouthpiece of religion or society. The writer’s legitimacy, in a “destitute time” (Hölderlin) of absent gods and silent sirens (Kafka) — a disenchanted world (Schiller) which is still ours — becomes highly arbitrary.

Personally, financial difficulties have always diverted me away from my writing. Having said that, the necessity to write often stems (at least in part) from a feeling of dissatisfaction — a sense that something is missing — so, from that point of view, not being rich and contented is probably an asset.

In a rare 1983 interview the enigmatic and often dour Romanian writer Emil Cioran speaks about only reading Nietzsche’s letters because he became concerned with how untruthful Nietzsche’s published works seemed when read against the miserable condition of his day to day existence (isolated, weak, sickly, certainly not characterized by any sense of vigor). Is there any sense in which the truth of one’s condition should be related to the truth of one’s writing, even if in an oblique sense?

In an oblique sense, yes; otherwise, not necessarily. As I was saying, literature is often a compensatory activity; an elaborate form of wish-fulfilment. I am absolutely fascinated by the impact that someone’s physical and psychological life can have on his/her thinking and writing — how apparently rational choices are due, for instance, to a tiny todger, short stature, child abuse, or the absence of a parent. Sartre claimed that he began writing to make up for his ugliness and impress women. We all want to be loved, and writing is always a love letter of sorts. As Richard Brautigan put it, “Just because people love your mind, doesn’t mean they have to have your body” — but one lives in hope, of course.

Perhaps Cioran’s remark makes more sense in the context of philosophy, but literature is the space of contradiction and ambiguity, and that’s what interests me.

Incidentally, I once lived in the same street as Cioran, in Paris.

Are you envious of other people’s success? If so, are you more envious of people’s success in your field or outside of it? Why?

I am, especially if I think they don’t deserve it. I’m more envious of people in my own field, of course, because I feel closer to them. It’s a phenomenon that René Girard skillfully analyses in Deceit, Desire & the Novel.

Give one example in which you had high hopes for success (artistic, commercial, or otherwise) but had those hopes dashed.

When I was really young, and still a student, I got a contract with an American publisher for a short work of criticism. I’d sent them the manuscript, on the off-chance, and it turns out that they wanted to publish it as it was. I was really proud: I didn’t know anyone my age who had published a book — but, of course, I wasn’t satisfied. The manuscript, in my eyes, wasn’t good enough. I asked the publisher to give me a little time to work on it. They granted me a one-year deadline, on the understanding that I’d send in the revised manuscript after six months. Six months, that’s all you need, they said, six months. Almost five years later, I was still working away on the manuscript, wracked by guilt, and I had to draw the conclusion, eventually, that the project I’d embarked upon was unfinishable. As Blanchot said of Joubert, I preferred failure to “the compromise of success” — or at least, that’s my excuse.

Do you feel like the world owes you a chance to make a living as a writer?

Absolutely not, but I hate the world for it!

What is the strongest emotional reaction you have ever elicited from a reader, either in your written work or during a reading? What is the strongest emotional reaction you have ever elicited from yourself during the writing process?

When people I respect have told me that they wished they’d written a story of mine.

When I’ve managed to write something so painful that I thought I’d never see it through.

When, on the rare occasion and in the distant past, women have wanted my body, just because they loved my mind.

When are you at your most truthful as a writer?

When I’m not writing.

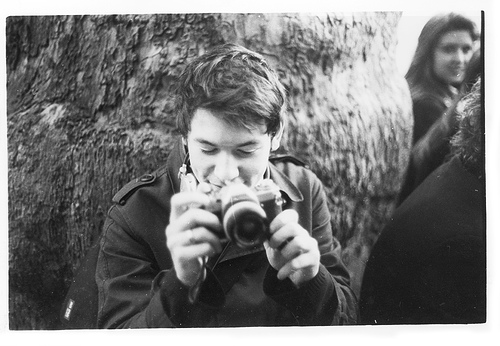

3:AM: This meeting of the old and the new also reflects recent trends in photography: digital cameras and the Internet have led to a paradoxical revival of interest in film and analogue cameras. You choose to shoot film but post scans of your pictures on your blog and on Flickr (where they are viewed by hundreds of people). Do you agree that the two media seem to complement each other?

3:AM: This meeting of the old and the new also reflects recent trends in photography: digital cameras and the Internet have led to a paradoxical revival of interest in film and analogue cameras. You choose to shoot film but post scans of your pictures on your blog and on Flickr (where they are viewed by hundreds of people). Do you agree that the two media seem to complement each other?