This piece appeared in Bomb Magazine on 8 May 2014:

Nicholas Rombes by Andrew Gallix

Constraint as liberation, knife-wielding film scholars, and the human brain as total cinema machine.

Still from the ten-minute mark of The Foreigner, 1978, Amos Poe.

There was a time when movies lived up to their name. They moved along and, once set in motion, were unstoppable until the end — like life itself. What you missed was gone, lost forever, unless you sat through another screening, and even what you had seen would gradually fade away or distort along with your other memories. I recently happened upon a YouTube clip from a film I had first watched in 1981. I thought I knew the scene well, but it turned out to be radically different from my recollection: the original was but a rough draft of my own version, which I had been mentally honing for more than three decades. Such creative misremembering — reminiscent of Harold Bloom’s “poetic misprision” — is now threatened by our online Library of Babel.

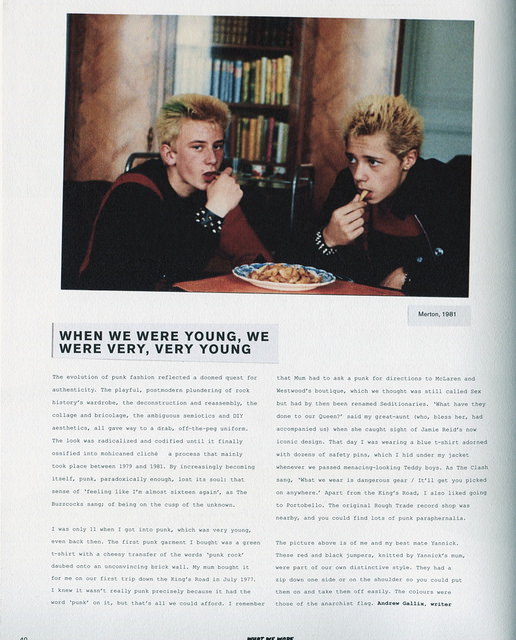

According to Nicholas Rombes, who is spearheading a new wave of film criticism, movies surrendered much of their “mythic aura” when they migrated from big screens to computers via television. Indeed, since the appearance of VCR, spectators have been able to control the way movies are consumed by fast-forwarding, rewinding, and — most importantly, at least for digital film theorists — pausing. If such manipulations run counter to the magic evanescence of the traditional cinematic experience, Rombes manages to recast the still frame as a means of creative defamiliarization and re-enchantment. In 10/40/70: Constraint as Liberation in the Era of Digital Film Theory, he freezes movies at ten, forty, and seventy minutes. The resulting motionless pictures take on the eerie quality of Chris Marker’s 1962 masterpiece La Jetée, famed for its cinematic use of still photography. But soon the frozen frames Rombes burrows into start to move again — and in mysterious ways. They are rabbit holes leading to subterranean films within films.

In the bowels of an appropriately warren-like cinema, I met up with Rombes, whose criticism, artwork, and fiction are taking on the shape of a beautifully intricate Gesamtkunstwerk. Over several (too many?) espressos, we mapped out the treacherous critical terrain he excavates in this latest book. The danger “of staring too long into frozen images” and the fear of being swallowed up by gaps between frames were visible in his eyes.

Andrew Gallix For you, digital film theory is an attempt to retrieve something — “traces of something that was always there, and yet always hidden from view.” From this perspective, the 10/40/70 method has led to a significant discovery: the importance of what you call “unmotivated shots” — shots that do not strictly advance the storyline but, rather, contribute to the general mood. You go so far as to say that such moments, when directors seem to be shooting blanks, are “at the heart of most great movies.” In The Antinomies of Realism, critic and theorist Fredric Jameson argues that the nineteenth-century realist novel was a product of the tension between an age-old “storytelling impulse” and fragments through which the “eternal affective present” was being explored in increasingly experimental ways. Can we establish a parallel here with your two types of shots — plot versus mood? Are these unmotivated shots the expression of a film’s eternal affective present, perhaps even of its subconscious?

Nicholas Rombes This opens up a really fascinating set of questions about cinema’s emergence coinciding with the height of realism as both an aesthetic and as a general way of knowing the world. I’ll backtrack just a bit. In his 1944 essay “Dickens, Griffith, and the Film Today,” Sergei Eisenstein explored the relationship between Dickens-era realism and montage in cinema as pioneered by D. W. Griffith, specifically in his use of parallel editing. Eisenstein quotes Griffith explicitly acknowledging that he borrowed the method of “a break in the narrative, a shifting of the story from one group of characters to another group” from his favorite author, Charles Dickens. And that tension between the ever-present affective experience of watching a film or reading a book and the internal world of narrative time is beautifully explored in Seymour Chatman’s Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film. He draws a distinction between “story” (events, content) and “discourse” (expression). I prefer Chatman to Jameson here only because there is a boldness and a confidence to Chatman’s structuralist rendering with its charts, diagrams, and timelines. But yes, the messy correlation between the informational mode of a film still and the affective mode is a mystery. For me, a sort of enforced randomness — selecting the seventy-minute mark, no matter what — is an investigative tool for prying open this mystery. The element of chance is key. This method of investigation is opposed to hermeneutics, insofar as it approaches the text backwards. That is, rather than beginning with an interpretive framework, it begins with a single image I had no control over selecting. Whatever I’m going to say about the image comes after it’s been made available to me, rather than me searching for an image to illustrate or validate some interpretation or reading I bring to it.

AG The seventy-minute-mark screen grab of The Blair Witch Project (1999) just happens to be “the single most iconic image of the film,” but such serendipity is rare. In the case of a monster movie like The Host (2006), for instance, the 10/40/70 method fails to yield a single picture of the creature. As a result, your approach tends to defamiliarize films by pointing to the uncanny presence of other films within them — phantom films freed from the narcotic of narrative:

Such moments could be cut or trimmed without sacrificing the momentum of the plot, and yet the cast-in-poetry filmmakers realize that plot and mood are two sides of the same coin and that it is in these in-between moments — the moments when the film breaks down, or pauses — where the best chances for transcendence lie. […] It is in moments like these that films can approximate the random downtimes of our own lives, when we are momentarily freed from the relentless drive to impose order on chaos.

As this quote makes clear, your constrained methodology is “designed to detour the author away from the path-dependent comfort of writing about a film’s plot, the least important variable in cinema.” It is often a means of exploring the “infra-ordinary” — what happens in a film when nothing happens, when a movie seems to be going through the motions. One thinks of Georges Perec, of course, but also of Karl Ove Knausgaard, who recently explained that he wanted “to evoke all the things that are a part of our lives, but not of our stories — the washing up, the changing of diapers, the in-between-things — and make them glow.” When such in-between moments lose their liminality, do they become “moments of being” (to hijack Virginia Woolf’s expression) during which a movie simply is?

NR I think they do, and I very much like that phrase from Woolf. At the heart of this is the notion that films — all films — are documentaries in the sense that they are visual records of their own production. In a narrative film, for instance Ben Wheatley’s A Field in England (2013), we have a documentary record of so many things: the actors playing their roles; the landscape, whether natural or constructed; and of course filmic technology itself, insofar as the film is created with equipment that, in recording the narrative, is also leaving behind traces of itself. This is much easier to see in older films that are historically removed from us (i.e., a Griffith film “looks” filmic and reminds us of the technologies of, say, 1906 or 1907) or films that call for immediate and sustained attention to the process of their production (again, The Blair Witch Project). And, in that sense, as documentaries, I like to think that no matter how controlled, how airtight, how totalizing their efforts to minimize chance are, there will always be gaps, fissures, eruptions of the anarchy of everyday life. Even in something so small as the accidental twitch of an actor’s face, or the faint sound of a distant, barking dog that “shouldn’t” be in the film but is, or the split-second pause in a actor’s line and the worry that crosses her face that suggests she is really thinking about something else, something far apart and far away from the movie at hand. And so that’s one of the things I’m hoping to capture in pausing at ten, forty, and seventy minutes, though any numbers would do.

AG What was experimental in the context of the nineteenth-century novel has long been deemed conservative in the field of film. This, you argue, is due to “the near-total triumph of montage,” which “mutilated reality” through its depiction of “fractured time.” But Eisenstein-style dialectic montage is now the “dominant mode of advertising and a tool of media industry” — think “fast-paced cutting and MTV.” This led, by way of opposition, to the rise of neo-realist “long-take aesthetics,” ushered in by digital cinema, paradoxically a technology once thought to “represent a final break with the real.” Could you talk us through this?

NR The single-shot films of the Lumière brothers, though most lasted less than a minute, contained no cuts: they were continuous, real-time shots. These early films are often discussed as “actualities,” which is not helpful in that it suggests that cinema evolved out of this into its “inevitable” status as narrative/fiction, a supposed higher-order form of storytelling. Although it’s been an enormously productive way to think about early single-take cinema, it’s also created a binary that privileges so-called artifice (“art”) over so-called naive representations of reality. For André Bazin, long-take aesthetics, based in the Lumière films, are in some ways a moral act, one that had the radical potential to reveal, rather than to obscure, God’s created world. In his 1955 essay “In Defense of Rossellini,” he wrote:

[T]o have a regard for reality does not mean that what one does in fact is to pile up appearances. On the contrary, it means that one strips the appearances of all that was not essential, in order to get at the totality in its simplicity.

It’s easy to see why Bazin came under such withering assault by the post-structuralists in the 1960s and 70s, for whom words like “essential” were anathema, and for whom reality itself was always already a construct. And yet, a society gets the technology it deserves, and Bazin could only praise the long takes he was given — those in the films of Orson Welles, for instance, or Theodor Dreyer. This was an era when the typical motion picture camera magazine only held enough film for a ten to twelve-minute shot. So I would say that we have come full circle. Films like Alexander Sokurov’s Russian Ark (2002) show that narrative film can be made without any montage.

Still from the forty-minute mark of The Foreigner, 1978, Amos Poe.

AG One of your sources of inspiration was Roland Barthes’s 1970 essay, “The Third Meaning: Research Notes on Some Eisenstein Stills.” Do you share the French critic’s view that a static movie frame is neither a moving image nor a photograph?

NR Yes. One of the things Barthes suggests in that essay is that a “still is the fragment of a second text whose existence never exceeds the fragment; film and still find themselves in a palimpsest relationship without it being possible to say that one is on top of the other or that one is extracted from the other.” With digital cinema all sorts of wonderful complications come into play: in what sense, say, are film frames “frames” in digital filming, processing, and projection? And what’s the ontological status of an image that exists as ones and zeros? But no matter what the technology, the idea is the same: a “stilled” image from or of (in the case of a still versus a frame) a motion picture exists at a weird threshold, and, Barthes suggests, we might as well say that it’s not the paused image that’s extracted from the film, but the film itself which is extracted from the paused image. That’s the secret world I hoped to enter through intense scrutiny of an individual frame. This secret world, however, is perilous, and my own experience dwelling for so long in these film frames is that the tug of motion is sometimes still alive in them, perhaps like a cadaver that suddenly shudders for a moment with a trace of life. I found the experience altogether unsettling and even frightening.

AG Have you ever considered applying the 10/40/70 method to movies you’d never seen before? What kind of result would that produce, in your view?

NR I very much like this idea — sort of like flying blind. Without the context of having seen the movie to appreciate not just its plot but its texture and mood, the 10/40/70 method would coerce me into focusing even more on the formal qualities of the three frames in question. This would be especially true if it was a film that I not only hadn’t seen, but also had never even heard of before. Stripped of context, I wonder if the frames would assume something more akin to the status of photographic images, truly “stilled” in a way that’s impossible if you’re already familiar with the film.

AG Could you comment on the pleasing congruence between theory and practice — the “frozen moving image” being, as you point out, “the ultimate long take”? Something similar happens in the “Intermission” chapter, where your text mimics the split edit technique under discussion. In fact, one could argue that the 10/40/70 method itself produces a series of textual approximations of split edits. Is this continuity between writing and film a quest for a cinematographic writing style?

NR The theorists who’ve meant the most to me — such as Julia Kristeva, Roland Barthes, Jean Baudrillard, Laura Mulvey, Robert B. Ray, bell hooks, Eugene Thacker — perform their ideas through the shape and tenor of their prose, and that’s something I’ve aspired to, especially in 10/40/70, where the split edits between formal analysis, personal reflection, and theory hopefully generate, if only in flashes, the same sort of feeling you get when a film suddenly bares its teeth and shows you that it wasn’t what you thought it was. But I will also say there is a dark gravity at work in certain of the film frames, perhaps because portions of the book were written during a very low point for me. The film frame — motionless — doubling as a long take was an idea born of desperation, of staring too long into frozen images.

AG You quote André Bazin, for whom the power of a movie image should be judged “not according to what it adds to reality but to what it reveals of it.” Do you agree that this would provide an excellent description of your own analytical method, which is all about revealing something as yet unseen? On at least a couple of occasions, you acknowledge that there is “very little to say about [a] scene that is not outstripped by the scene itself.” On others, however, you adopt a more hands-on approach — by projecting a scene from The Passenger (1975) onto Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974), or by splicing together a movie and a novel — as though the 10/40/70 constraint were no longer enough.

NR Well, I do think some films theorize themselves and suffer from the words we use to untangle them. I’ve gotten in some terrible rows with colleagues about this over the years. In fact, one of the sections I deleted from the book described a knife fight between a fellow graduate student and myself at Penn State in 1992. It was about Wild at Heart (1990). After a long night of arguing and drinking Yuengling, I said something like, “that movie doesn’t need your theory because it’s already theorized itself,” then there was some unfortunate language that escalated into an actual, awkward fight with knives. Some film moments are diminished, rather than enlarged, by the words we bring to bear on them. As I’m answering this question I’m reading a novel by Jeff VanderMeer called Annihilation, and there’s a moment when the narrator realizes the enormity of the mystery she’s trying to understand: “But there is a limit to thinking about even a small piece of something monumental. You still see the shadow of the whole rearing up behind you.” For me, during the writing of 10/40/70, that shadow was the realization that the constraints I established were weak and insufficient against the tyranny of interpretive intention.

AG Your book is, among many other things, a rehabilitation of Bazin — what is his significance today? Could you explain what you mean when you claim that his “total cinema” is the “end point” of digital cinema?

NR Bazin was interested in excavating the desires that fueled the invention of moving images — desires that he suggests were based on a passion to create an utter and complete replication of nature. In his 1946 essay “The Myth of Total Cinema,” he suggests that what energized this desire was “the recreation of the world in its own image, an image unburdened by the freedom of interpretation of the artist or the irreversibility of time.” He says that the myth (i.e. the desire to replicate reality entirely) preceded the technology that made it possible. The tricky thing here is Bazin’s use of the term myth, which he doesn’t seem to equate with “false.” Instead, he almost suggests that this myth is achievable, as in his point that the flight of Icarus remained in the realm of myth only until the invention of the internal combustion engine. In this regard, Bazin occupies a fascinating and precarious place in film theory. While his approach has something in common with the later “apparatus theory,” which historicized film production, he decidedly didn’t share their assumptions about the ideological contamination of cinema’s very technology, instead framing that ideology within the larger and more important (for him) question of human desire and aspiration. By linking total cinema to a terminal, or end point, I’m wondering if we have achieved, on a symbolic level, Bazin’s notion of the recreation of the world in its own image. Doesn’t the surveillance state suggest this? On a practical level — and linking straight back to Bazin’s terms — it’s possible to have a camera, or multiple cameras, capture in a continuous, uninterrupted shot an object or a place and to keep recording this for as long and longer than you and I shall live. This one-to-one replication, to use Bazin’s term, of reality that unfolds contiguous with time itself, stretching decades with no interruption, with no need for interpretation, was not possible in Bazin’s era, except as a theory.

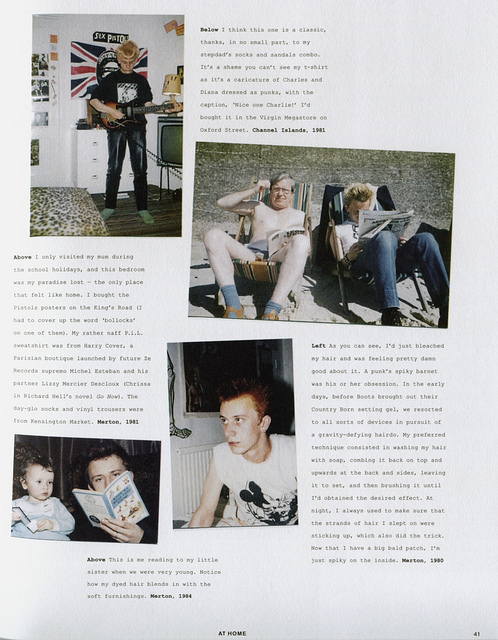

Still from the seventy-minute mark of The Foreigner, 1978, Amos Poe.

AG You suggest that the true, ultimate long take may be human perception itself: “a lifespan unfolding in real time, punctuated by cuts and fade-outs that take the form of blinking and sleeping and forgetting.” What’s at stake for you in film criticism is far more than just film criticism, isn’t it? I’m thinking especially of passages where you apply the 10/40/70 method to your own memories: “There was yet no logic. No 10/40/70. No sense that images could be tamed only to be let loose among their tamers.” Could you comment upon that last quote, which reminds me a little of Raymond Queneau’s definition of Oulipians as “rats who build the labyrinth from which they plan to escape”?

NR There was a deep sadness that accompanied the writing and assembling of the book, and your question touches on the nature of that sadness, which I think has to do with realizing that theory — whether it’s 10/40/70 or any theory — is an attempt on some level to structure and impose some sort of narrative coherence on our very selves and memories. Our brains are the most vicious total cinema machines of all. Our continual efforts when awake and when sleeping to work out the past, to smooth it into layers of meaning, must certainly wear the gears down until we can’t even hear or feel them moving. Forced into a high level of concentration we come to realize that it’s not films we’re talking about, but ourselves. Our fingerprints are already over everything.

AG At times, the book does become darkly autobiographical. This appears to be the case towards the end of the piece on Lindsay Anderson’s If… (1968) and clearly is throughout your Lynchian “Intermission” and “Epilogue,” which often read like short stories. The screenplay you’ve written, The Removals, seems to be, if the teaser is anything to go by, about the gap between life and art, which all the major avant-garde movements of the twentieth century aspired to bridge. Please tell us about the interaction between criticism, autobiography, and fiction in your work in general, and your forthcoming novel, The Absolution of Roberto Acestes Laing, in particular.

NR I’m reluctant to talk about this, so forgive me if my answer is a bit elliptical. There are certain things that have happened to me that don’t seem possible, but that bear witness to truth. The terrible knife fight is one. Criticism, autobiography, and fiction are linked by the desire to uncover what lies beneath and, as you suggest, to fatefully go into the gap between art and life. Once you enter this gap you use every genre and mode of writing to close it, only to realize that in the process you’ve created something new, something in between life and art, and it’s so fragile you dare not talk about it. The Absolution of Robert Acestes Laing is about the frightful consequences of what happens when this gap decides it doesn’t want to be bridged and strikes back.

AG Your constraint-based approach was directly inspired by Dogme 95, but what about the Oulipians: how much of an influence were they? Were you, for instance, aware of the Oucinépo, launched by François Le Lionnais in 1974, which was later renamed Oucipo (Ouvroir de Cinématographie Potentielle) and appears to have done precious little? Could you also talk to us about other sources of inspiration: Laura Mulvey, certainly, but perhaps also Douglas Gordon’s art installation, 24 Hour Psycho?

NR Oulipo has always been a low-frequency inspiration, although I didn’t always know it. I think I was first introduced to them through Brian Eno and Brian Schmidt’s Oblique Strategies, and then worked my way back to Georges Perec. Oulipo must have been somewhere in the back of my mind when coming up with 10/40/70, but it was much more, as you say, the Dogme 95 movement that served as a direct inspiration. It seemed more outrageous to me, more difficult to get a handle on in terms of sincerity and irony. 24 Hour Psycho — yes, but also, now that I think about it, there was a more obscure and personal inspiration. Our children and their friends went through a phase when they were maybe eleven or twelve (this would have been in the early 2000s) when they used the term “random” in a sort of complimentary way. I distinctly remember my daughter Maddy saying, from the back of the car, “that’s so random, Dad!” in response to something I had said. It signaled to me — and I remember very strongly feeling this — that I was, for that one brief moment, in her world, that I had accidentally and momentarily become “cool” because what I had said was “random.” And the movies and video games and even music they were attracted to had elements of this feeling of randomness: sampling, the choose-your-own-adventure-first-person-exploration video games like Metroid Prime (2002) and TV shows like Lost (which debuted in 2004) and which had this feeling of randomness, chance, and risk.

AG You discuss the essentially random nature of the 10/40/70 constraint, but say nothing of the conscious choices that were made while composing this work. How did you go about selecting the films and their order of appearance in the book?

NR This is embarrassing, but prior to the book I had worked out what I thought was an arbitrary method for selecting films. This involved using the IMDB database of all films released in a certain year and having various acquaintances select one from each. But there were so many problems with that, not least of which is that for, say, 1997, there are over forty thousand movies listed, and what are movies anyway? Is a direct-to-TV movie a movie, or is a movie released directly to VOD a movie, or what about a movie made for TV but thought of as a motion picture — like Spielberg’s Duel (1971)? And there are thousands of porn titles listed there, too. And then there were other methods, including a Lev Manovich-like algorithm that used a database and random generator to select films. But finally all these seemed too impersonal and involved — a sort of fakery, a false sheen of objectivity. So I used the limits I had at hand: my own collection of films, which didn’t always represent my tastes because many of them I had purchased simply to illustrate a technique in my film class. My one strict rule was that once I selected a film, I’d write about it no matter what, no matter what it revealed, or didn’t reveal.

AG Perhaps you could say a few words about other similar projects like “The Blue Velvet Project” or “The 70s”?

NR The original idea for “The Blue Velvet Project” was to purchase a 35 mm print of the film, digitize it, and work on each frame, but of course there’s no way to do that in a lifetime, as there are close to 1,500 frames in just one minute of film time. This idea eventually morphed into the project that ran at Filmmaker for one year, where I stopped the film every forty-seven seconds, seized the image, and wrote about it. A goal there was to take a film I was familiar with and devise a method of writing about it that would, as much as possible, dispense with interpretive intention and to subject myself to the film’s interrogation. With “The 70s” I’ve opened the call to anyone who wants to send me a frame grab from the seventy-minute point of a film, partly to see whether there is any weird correspondence, affinity, or secret knowledge passed back and forth between films at seventy minutes.

AG Post-VCR technology has transformed film theory, but has it also influenced film practice? Was this something you took on board when writing the script for The Removals, directed by Grace Krilanovich?

NR Yes, in the sense that I still don’t believe we’ve acclimatized to the radical displacement of actually seeing and hearing ourselves broadcast back to us, as film made possible only a little over a hundred years ago. This displacement — or removal — of ourselves from ourselves was first made adjustable by the VCR and other early forms of image playback technology. The Removals is a thriller in the sense that it’s about the revenge of this second or third or fourth copy or iteration of ourselves on ourselves. Robert B. Ray has written elegantly — in How a Film Theory Got Lost and Other Mysteries in Cultural Studies — about how film theory, especially in the US, suffered a blow to the imagination by adopting a vague sort of social sciences approach to hermeneutics. One of his suggestions is to view film theory as a form of radical experimentation. What would happen, say, if I adopted the editing style of film X as a method of inquiry? The overall goal is to find something new and unexpected, not just in the film itself, but in the writing about the film.

AG Would you like to try your hand at directing some day? Perhaps you could ask Grace Krilanovich to write a script for you.

NR I have all the props to be a director: an eye patch, a Colt single-action Army revolver, and an ascot à la Dom DeLuise in Blazing Saddles. If I directed a film it would be incoherent, but hopefully in the way that Robin Wood uses that term in his great book Hollywood From Vietnam to Reagan.

AG Your earlier work, Cinema in the Digital Age, highlights the ways in which digital films were haunted by their analogue past. Do you think this is still the case?

NR Perhaps not so much as I thought when I wrote that book, and in fact I’m working on a new edition which will address just this question. I bring, as someone born in the 1960s, a certain generational perspective to the analogue/digital transformation, as it unfolded in real time for those of us from that era. But my university students today were born in the 1990s and came of age in the 2000s, on the digital side of history. Also, the haunting that I described, especially in self-consciously digital films, such as those from the Dogme 95 movement, seems to be characterized by suppression. It’s in the efforts to suppress vestiges of cinema’s analogue customs — mise-en-scène, depth of field, shot reverse-shot, etc. — that digital cinema, paradoxically, reveals traces of those very customs. In their absence, they remain. In Lars von Trier’s The Idiots (1998), for example, efforts at ugliness are undermined by our own weird form of metatextual tmesis, which Barthes described as skipping or skimming around in a text, rather than reading it word-for-word. In the sort of tmesis I’m thinking about, we as the audience sporadically fill in the empty spaces and derail The Idiots’ digital attempt to break free from analogue aesthetics: we substitute blank ugliness with mise-en-scène and we credit shaky camera movement. In this sense it may be that it is the spectator herself who haunts digital cinema.

AG Punk is another important point of reference we have failed to mention so far. You have written a book about The Ramones’s classic debut album and A Cultural Dictionary of Punk 1974-1982, as well as edited an anthology devoted to New Punk Cinema.

NR I’m almost ashamed to talk about punk, as I was drawn to it because it repelled me. I wanted to learn more about what this thing was that came along, then destroyed and made laughable the music that I loved. I read Greil Marcus’s Lipstick Traces and then Jon Savage’s England’s Dreaming, and I suppose, to be honest, I wanted to write heroically, as I felt they had. My goal in the 33 1/3 book, devoted to the first album by the Ramones, was to bring to bear upon that material a highly rigorous, almost exaggerated academic method and tone to try to capture what I felt was the cold, removed, distanced feeling of that album. For A Cultural Dictionary of Punk, I switched gears, and will be ever grateful to my editor David Barker (then at Continuum Publishers) who gave me full permission to drive the bus off the cliff, as it were, to see what the crash would look like. So there’s an alter ego in that book — Ephraim P. Noble — who despises punk and who writes some of the entries. But it’s also a heavily researched book, and I hope that it succeeds in drawing connections between the deep tissue of punk and other cultural forms that it corresponded to in coded ways.

AG To return to 10/40/70, does Zeno’s (the bar which casts a Lynchian shadow over the autobiographical “Intermission” chapter) really exist? It seems too good to be true, given that the Greek philosopher — a digital film theorist avant la lettre — is known for his paradoxical arguments against motion.

NR Zeno’s seems too good to be true, but it exists, and was a favorite watering hole for those who wished to get drunk on more than theory in grad school. There was a woman there who tended bar whose face really was melted like wax and who would say things under her breath in a language I didn’t understand, but that someone — a linguist we used to hang out with — said was Coptic. I haven’t been back there for twenty years, but I remember it was one of those bunker-like places beneath an old building, very dark, and the space was difficult to understand. Was it an enormous room, or simply a room that, by its lighting, seemed enormous? Sort of an interior version of the Zone from Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979).

AG Has Detroit — where you teach — influenced your work?

NR I’m sure it has — both the city and the place where I work, the University of Detroit Mercy, which has been supportive of all my work, no matter how much it has strayed. The university was founded by the Jesuits and their mode of intellectual inquiry about the created world has inspired and sustained me. I was hired in the mid-1990s as an early Americanist in the English department, having written my dissertation on the late eighteenth-century rise of the gothic novel in the United States. I still teach and do research in that field, but the connections I sensed between the messy dialogism and heteroglossia of the early novel — especially emerging out of a Puritan context, as it did in the US — and similar dialogic noises that punk made, felt natural to me and worth pursuing.

And I drive each day through parts of the city that still bear physical scars of the 1967 riot — or insurrection, as it is called by many in these parts. It can be a strange and exhilarating feeling, like looking at sedimentary rock with its exposed layers of time. Where other cities, through gentrification, “urban renewal,” and the like, have eradicated traces of their past, unless they are pleasing to look at, Detroit retains an almost documentary-like record of its violent past, though not by choice. There is such a strong feeling in Detroit that you have to push very hard through history to be and to exist in the present, and this constant state of adjustment gives people here, I find, a very high sense of alertness and clarity.

****

The first question was cut during the editing process. I eventually worked part of it into the introduction. Here it is, for the record:

AG In the Preface, you claim that films surendered much of their “mythic aura” when they migrated from big screens to computers via television. This “demystification” — that represents yet another stage in Schiller’s disenchantment of the world — is largely due to the fact that movies have lost their relentless forward momentum. Since the “advent of VCR,” spectators have been able to control the way films are watched: they can fast-forward, rewind, and — most importantly for digital film theorists — pause. The “ability of even the most technically handicapped users to capture video and film frames” runs counter to the traditional “fleetingness” of the cinematic experience — “the impossible-to-stop movement of images across the screen, the ways in which the audience remembered and misremembered certain moments”. Do you agree, with the likes of Mark Fisher or Simon Reynolds, that what we have lost in our digital age is loss itself?

NR I think it’s the feeling of loss, rather than loss itself, perhaps something akin to what Steven Shaviro describes as affect that doesn’t merely represent, but structures subjectivity. Lately, though, I’ve taken my deconstructive cues more from literature and film and less so from theory, so my responses will reference those sources a bit more than the usual theory suspects. A super-abundance, or plague, of meaning. That’s our curse. It’s not just cinematic images: our data centers, digital archives, cached pages, cloud storage — these suggest a weird distorted image of the surveillance state. It is not we who watch films, but films that watch us. My feeling is that this is expressed best through genre, horror specifically, perhaps because of all of cinema’s dirty genres, horror has always been about scopophilia (Laura Mulvey) more than anything else. Theory can be found, today, in the haunted images of the V/H/S films, the first three Paranormal films, and several Ti West films (especially The Sacrament) because the horror genre gives permission, somehow, to theorize not just space within the frame, but the nature of the frame itself. The V/H/S/ horror anthologies, for instance, remind us every twenty minutes or so (or whenever a ‘new’ tape is inserted) of the embodiment of horror in its precarious, unstable situation as its medium shifts from analogue to digital.