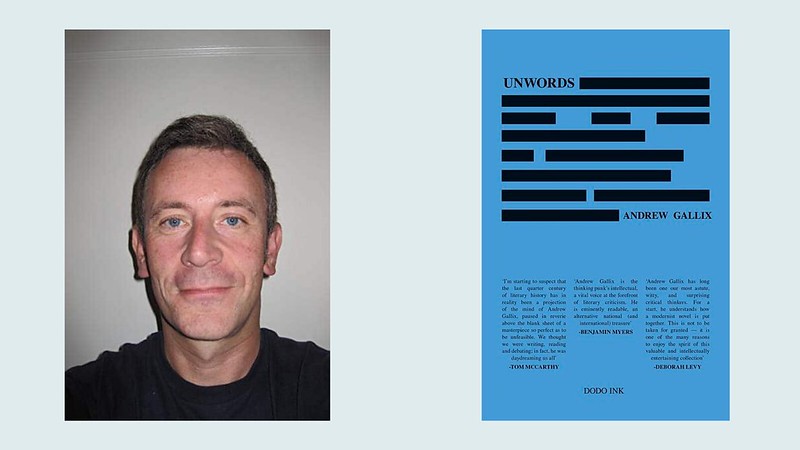

Nesbitt, Huw. “Reading and Writing: Thirty Years of Textual Snapshots.” Review of Unwords by Andrew Gallix, Times Literary Supplement, 14 June 2024, p. 25

Masquerading as a wide-ranging collection of literary essays, Unwords is in fact a hybrid work of critical theory and biography. A reader might object that literature is already brimming with such experiments. Yet few are delivered with Andrew Gallix’s charm.

Originally published in the TLS, the Guardian, the Irish Times and 3:AM Magazine, the literary website Gallix founded in 2000, the essays in this collection are written in crisp newspaper prose, avoiding the preponderant “I” and paragraph-long sentences frequently found in creative non-fiction. At the book’s heart sits the story of Gallix’s writing career. In 1990, he landed a deal with a publisher for a book about a “middling English novelist and playwright (dead)”. Then Gallix blew it, writing an unwieldy, unfinishable Gesamtkunstwerk instead. Undeterred, he took to criticism, opting to sketch a treatise on literature via freelance commissions.

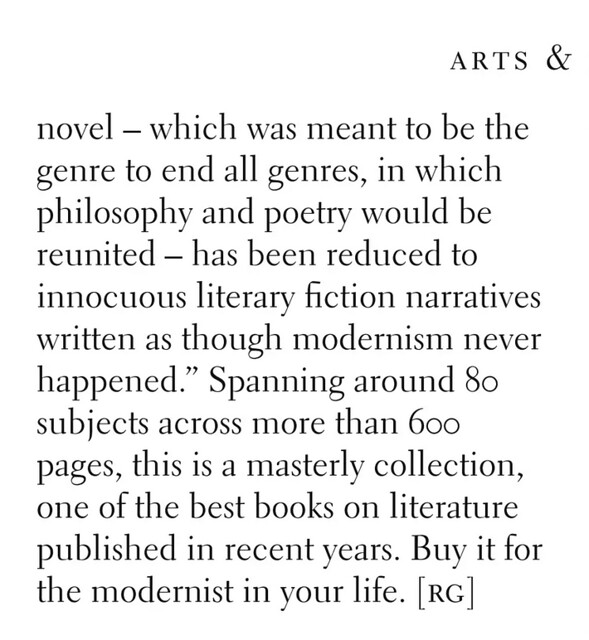

“The best authors … are wary of the consolations of fiction”, Gallix writes in an article on literary realism. “They sense that the hocus-pocus spell cast by storytelling threatens to transform their works into bedtime stories.” He prefers — and draws this collection’s title from — what Samuel Beckett described as the literature of the “unword”: fiction that isn’t just about something but is the thing itself. “The reality of any work of art is its form, and to separate style from substance is to ‘remove the novel from the realm of art'”, he notes in another essay, quoting the nouveau romancier Alain Robbe-Grillet.

To elaborate this thesis, he explores the work of authors often classed as stylists. Naturally there are big names: Jonathan Franzen, Joyce Carol Oates, Deborah Levy, Joshua Cohen. But, Gallix is equally at home with the obscure. “The book’s apparent lack of direction is part of a strategy … to ensure that it does not become another bogus piece of literary fiction”, he remarks of Lars Iyer’s Dogma (2012), a plotless novel about two bungling philosophy professors. “Perhaps what Tunnel Vision really aspires to be is a self-portrait without a self”, he observes of the Irish writer Kevin Breathnach’s autofictional debut (2019).

A sense of provocation permeates Unwords. This is reinforced by tributes to the Parisian punk icon Jacno (“He belongs to a long line of elegantly wasted rock dandies”) and the French-Egyptian postwar novelist Albert Cossery, who wrote only one sentence a day. For Gallix, literature doesn’t exist to be binged, to delight or comfort: novels are real objects requiring reflection, whose language and syntax very often lead us back to the world itself.

Unwords brings together thirty years of reading and literary contemplation. It offers what Roland Barthes termed biographemes, textual snapshots where life and literature are indistinguishable. “Simply put, life writing is writing as a way of life”, Gallix notes. From the disappointment of the book he never published, Unwords’ author has produced something rare: a work of criticism that aspires to the condition of art.

![]()