This appeared in The Guardian’s Comment is Free section on 20 July 2011:

From Jonnie Marbles to the Yippies: A History of Pie Activism

The attack on Rupert Murdoch is part of a tradition of patisserie activism — but shaving foam is no substitute for the real thing

[Nöel Godin, political custard pie thrower. Photograph: Van Parys/Corbis]

Jonathan May-Bowles (aka Jonnie Marbles), who attacked Rupert Murdoch during yesterday’s phone-hacking hearing, has all the makings of a formidable flan flinger. In his capacity as comedian-cum-activist, he embodies a kind of Platonic ideal of patisserie terrorism – that strange interface between slapstick and protest.

Pie-throwing as a political gesture has its roots in the Groucho-Marxism of the 1960s student uprisings and, more specifically, in the prankish happenings of the Yippies. Tom Forçade, the founder of High Times magazine, is usually considered to have perpetrated the very first political pie crime in 1970. Aron Kay, who came to be known as “The Yippie Pie Man”, followed suit, covering countless politicians and celebrities (including the mayor of New York City and Andy Warhol) in cream, between the late 1970s and early 1990s. Yesterday, he allegedly posted a message on a website giving his full support to May-Bowles: “Murdoch definitely needed a pie, for sure.” However, it was a Belgian anarchist who really put “patisserie guerrilla” on the map. One could argue that he even managed to turn it into an art form.

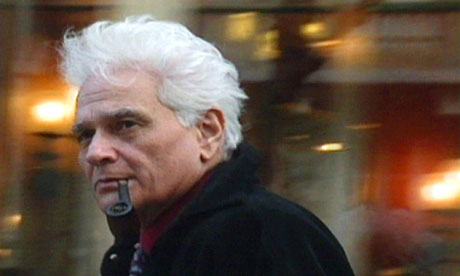

In the late 60s, Nöel Godin was, among other things, a film critic who amused himself by reviewing movies he hadn’t seen or that didn’t even exist. Georges Le Gloupier, a fictitious film director (invented by his partner in crime Jean-Pierre Bouyxou), made regular appearances in these reviews.

In 1969, Godin wrote that Le Gloupier had been so outraged by Robert Bresson‘s latest film that he had felt compelled to chuck a “Mack Sennett-style” pie smack in the director’s face. In a sequel, he went on to describe how the French novelist Marguerite Duras had avenged the initial “creamy affront” by giving Le Gloupier an impromptu pastry pasting while he was dining out in Saint-Germain-des-Prés. “Madame,” said the biter bit after licking his frothy chops, “I prefer your patisserie to your novels.”

Through some quirk of fate, the publication of the second article coincided with Madame Duras’s arrival in Belgium on a promotional tour. This proved a godsend to Godin, who decided to give a final twist to this burlesque saga. He ambushed the prime exponent of the “empty novel” and treated her to a real custard pie this time round. A visiting card was nestling in the incredible, edible weapon. It read: “With the compliments of Le Gloupier.”

The seminal Duras drubbing provided a blueprint for all the subsequent pie attacks. A few months later, it was choreographer Maurice Béjart‘s turn to fall victim to a Chantilly crime. By that time, Le Gloupier had acquired all his distinctive features: the refined dinner jacket and bow tie of gentleman-burglar Arsène Lupin, the false beard and spectacles of a cartoon, bomb-throwing anarchist and, last but not least, the absurd “gloup! gloup!” mantra. In the time-honoured tradition of Galatea, Pinocchio and sundry gingerbread men legging it after rising from the pastry board, Le Gloupier took on a life of his own: he started popping up all over the place, unbeknown to his creator, who was often associated with attacks he had taken no part in, but was only too willing to take credit for.

According to Godin, a well-aimed pie can break through the victim’s public image and lay bare his true character. New Wave director Jean-Luc Godard, for instance, reacted in good-humoured fashion and refused to press charges. By contrast, Bernard-Henri Lévy reacted violently and was flanned on at least five occasions as a result. The vendetta against the pop philosopher turned into a running gag in France.

The movement probably peaked in 1998, with the pieing of Bill Gates. Godin had now become a celebrity in his own right, and was frequently invited on live TV shows to be pied by presenters he had himself pied. The whole thing was descending into farce. However, the website of Godin’s “Internationale pâtissière” continues to advertise the latest pie attacks on a monthly, and sometimes even weekly, basis. The pieing of Murdoch could well be the sign of a revival.

Jonathan May-Bowles still has a thing or two to learn, though. A plateful of shaving foam is no substitute for the real thing. Godin once told the Observer: “We only use the finest patisserie ordered at the last minute from small local bakers. Quality is everything. If things go wrong, we eat them.”

****

Here is a longer (unpublished) version of the same piece:

Jonathan May-Bowles, who attacked Rupert Murdoch during yesterday’s phone-hacking hearing, has all the makings of a formidable flan flinger. In his capacity as comedian-cum-activist, he embodies a kind of Platonic ideal of patisserie terrorism — that strange interface between slapstick and protest. Pity, then, that he didn’t take a leaf out of Mack Sennett‘s book: “A mother never gets hit with a custard pie,” warned the Hollywood director, who knew a thing or two about the use of confectionery as weaponry, “Mothers-in-law, yes. But mothers? Never”. Old men are also a no-no, even if they happen to be at the head of an evil international media conglomerate. Pieing is always a difficult balancing act, a subtle blend of humour and anger, and in this case the first, vital ingredient was sorely lacking. Like the pie itself — a plateful of shaving foam — it wasn’t the real thing. Instead of shattering the spectacle (in Situationist parlance), May-Bowles has simply provided a perfect photo opportunity illustrating the metaphorical humble pie that Murdoch was already eating. Worse still, the media mogul may come out of this looking like the victim.

Pie-throwing as a political gesture has its roots in the Groucho-Marxism of the 60s student uprisings and, more specifically, in the prankish happenings of the Yippies in the United States. Tom Forçade, the founder of High Times magazine, is usually considered to have perpetrated the very first political pie crime in 1970. Aron Kay, who came to be known as “The Yippie Pie Man”, followed suit, covering countless politicians and celebrities (including the mayor of New York City and Andy Warhol) in cream, between the late 70s and early 90s. Yesterday, he allegedly posted a message on a website giving his full support to May-Bowles: “Murdoch definitely needed a pie, for sure!” However, it was Belgian anarchist Noël Godin who really put “patisserie guerrilla” on the map. One could argue that he even managed to turn it into an art form.

Like Aron Kay, Godin was influenced by the slapstick of the Three Stoges and the political ferment of 1968, but he also drew inspiration from the insurrectionary humour of late nineteenth-century French anarcho-pranksters like the Hydropathes or the Zutistes, to whom he paid homage in his anthology of radical subversion (Anthologie de la subversion carabinée, 1988).

In the late 60s, Godin was, among other things, a film critic who amused himself by reviewing movies he hadn’t seen or that didn’t even exist. Georges Le Gloupier, a fictitious film director (invented by his partner in crime Jean-Pierre Bouyxou), made regular appearances in these reviews. In1969, Godin wrote that Le Gloupier had been so outraged by Robert Bresson’s latest film, that he had felt compelled to chuck a “Mack Sennett-style” pie smack in the director’s face. In a sequel worthy of one of Joe Orton’s classic epistolary pranks, he went on to describe how the French novelist Marguerite Duras had avenged the initial “creamy affront” by giving Le Gloupier an impromptu pastry pasting while he was dining out in Saint-Germain-des-Prés. “Madame,” said the biter bit after licking his frothy chops, “I prefer your patisserie to your novels”. Through some quirk of fate, the publication of the second article coincided with Mme Duras’s arrival in Belgium on a promotional tour. This proved a godsend to Godin. The affair was causing so much fuss that the novelist was immediately forced to hold a press conference during which she repeatedly denied all prior knowledge of “Le Gloutier” (sic). Godin decided to give a final twist to this burlesque saga, thus illustrating Wilde’s dictum that life imitates art. He ambushed the prime exponent of the “empty novel,” and treated her to a real custard pie this time round. A visiting card was nestling in the incredible, edible weapon. It read: “With the compliments of Le Gloupier”.

The seminal Duras drubbing provided a blueprint for all the subsequent pie attacks. Le Gloupier’s metamorphosis into a latter-day noble bandit figure had occured overnight. A few months later, it was choreographer Maurice Béjart’s turn to fall victim to a chantilly crime. By that time, Le Gloupier had acquired all his distinctive features: the refined dinner jacket and bow tie of gentleman-cambrioleur Arsène Lupin, the false beard and spectacles of a cartoon, bomb-throwing anarchist and, last but not least, the absurd “gloup! gloup!” slogan. In the time-honoured tradition of Galatea, Pinocchio and sundry gingerbread men legging it after rising from the pastry board, Le Gloupier took on a life of his own, popping up all over the place, unbeknown to his creator, who was sometimes associated with attacks he had taken no part in, but was only too willing to take credit for.

According to Godin, custard pies are the weapons of “the weak and powerless” (L.A. Times). A well-aimed pie can shatter the pompous and vacuous public image of a celebrity in a matter of seconds. Le Gloupier’s targets (politicians, journalists, actors, pop stars, writers) are never selected at random (“Every victim has to be thoroughly justified,” The Observer) and his weapons are chosen with the same meticulous care (“We only use the finest patisserie ordered at the last minute from small local bakers. Quality is everything. If things go wrong, we eat them”). Pseudo-philosopher Bernard-Henri Lévy was flanned on five different occasions because he was “totally in love with himself” and epitomized “empty, vanity-filled literature”.

According to Godin, a well-aimed pie can break through the victim’s public image and lay bare his true character. New Wave director Jean-Luc Godard, for instance, reacted in good-humoured fashion and refused to press charges. By contrast, Bernard-Henri Lévy reacted violently and was flanned on at least five occasions as a result. The vendetta against the pop philosopher turned into a running gag in France.

The movement probably peaked in 1998, with the pieing of Bill Gates. Godin had now become a celebrity in his own right, and was frequently invited on live TV shows to be pied by presenters he had himself pied. The whole thing was descending into farce. However, the website of Godin’s “Internationale pâtissière” continues to advertise the latest pie attacks on a monthly, and sometimes even weekly, basis. The pieing of Murdoch could well be the sign of a revival.

Jonathan May-Bowles still has a thing or two to learn, though. A plateful of shaving foam is no substitute for the real thing. Godin once told the Observer: “We only use the finest patisserie ordered at the last minute from small local bakers. Quality is everything. If things go wrong, we eat them.”