Inés Martin Rodrigo has published an in-depth article on the Offbeats in top Spanish daily ABC in which I — “el Rimbaud de la Red”! — am quoted at length:

Inés Martin Rodrigo, “‘Se lo que sea, estoy contra ello,” ABC 16 February 2009

Es el lema de un nuevo grupo de escritores anglosajones con sede en Internet que está revolucionando la industria editorial. No tienen reglas ni manifiestos, pero la Generación Offbeat reclama su lugar en la escena literaria

La industria editorial es aburrida, está embotada y estreñida, desprende un cierto tufillo rancio y amenaza con eliminar todo fragmento de imaginación que aún quede en la mente del lector menos conformista. No es una sentencia categórica de un crítico cabreado con el ultimo best seller que ha llegado a sus manos, ni siquiera la reflexión concienzuda de un intelectual con complejo de Nostradamus. Es el pensamiento y la bandera literario revolucionaria de un nuevo grupo de escritores con sede en la Web y que se (auto)definen como Generación Offbeat.

Qué menos se podía esperar de los potenciales sucesores de Charles Bukowski, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs y compañía. Autores todos ellos enraizados en la libertad y el compromiso con ser fiel a uno mismo, filosofía de la que dieron buena cuenta en sus años de lucha literaria con las armas de las que disponían. Las armas de la razón hecha palabra y empleada en defensa de la paz, en contra de la Guerra de Vietnam o como sagaz discurso contra el recalcitrante conformismo de la sociedad de la época.

Una generación pegada a los libros

Los años han transcurrido y el discurso se ha transformado, al igual que las armas para evocarlo y defenderlo. Pero la raíz prendió con fuerza en una generación de jóvenes que creció leyendo el “Junky” de Burroughs, “uno de los mayores trabajos literarios sobre el mundo de la droga, al lograr algo que muchos libros que le siguieron fueron incapaces: habló del modo de vivir de un drogadicto”, en palabras de Tony O’Neill, escritor offbeat por excelencia. Y es que Burroughs describió el oscuro laberinto de la drogadicción sin ejercer de falso predicador para el lector, sin miedo a llamar a cada cosa por su nombre. Porque, le pese a quien le pese, un heroinómano no será nunca un pervertido al que adoctrinar. Así, llamando a las cosas por su nombre y leyendo, sobre todo leyendo, empapándose de los popes del movimiento beat fue como este grupo de autores fue regando su propio discurso.

Un discurso que se vertebra en un nuevo y excitante trabajo de ficción, que corre riesgos y que, cada vez con más intensidad, empieza a generar demanda en cuantos lectores se topan con él casi sin pretenderlo. Y es que, demasiado ácidos, diferentes y afilados para la industria editorial tradicional, la generación offbeat se esconde (de momento, aunque cada vez menos) en los amplios (y libres) márgenes de la Web y en alguna que otra editorial independiente.

El origen del movimiento

El primero en usar el término offbeat (y por tanto quien lo acuñó) fue Andrew Gallix, redactor jefe y responsable de la revista literaria online 3:AM Magazine (puestos a hacer comparaciones, valdría decir que sería algo así como el New Yorker de los offbeats). De eso hace ya casi tres años aunque, como el propio Andrew reconoce, “el movimiento llevaba bastante tiempo emergiendo. Es un poco lo que pasó con el punk o los nuevos románticos, al principio no tenían nombre por lo que mucha gente desconocía su existencia”.

Un desconocimiento que se fue disipando a medida que los grupos fueron proliferando en el ciberespacio. Eran escritores, guionistas, periodistas, bloggers, artistas… con un interés común por la literatura pura (sin artificios), que empezaron a gravitar alrededor de 3:AM y a organizar lecturas, conciertos e incluso festivales. “Fue en esos eventos donde comenzaron a establecerse las relaciones –explica Gallix-. La primera vez que fui consciente de que había aparecido un nuevo movimiento fue en el baño de Filthy Macnasty’s (uno de los pubs londinenses preferidos por Pete Doherty), cuando Lee Rourke (escritor y a la postre integrante de la Generación Offbeat) se abalanzó sobre mi y empezó a hablar de la enorme revolución literaria que habíamos iniciado. Aquello fue realmente el comienzo de todo”.

Un inicio virtualmente surrealista para un movimiento con integrantes de carne y hueso. Son muchos los offbeats que, incluso sin saberlo, engrosan la lista de esta generación pero, si hubiera que etiquetar al movimiento como tal cabría decir que se caracteriza por la variedad de voces y estilos y la ausencia de reglas (aquí no hay manifiestos). “A pesar de la diversidad, muchos escritores offbeat comparten características. La mayoría son británicos, treintañeros y creen que la escritura es mucho más que un mero entretenimiento”, enfatiza Gallix. Y sienten la música como elemento catalizador y de equilibrio.

Una lista repleta de talento

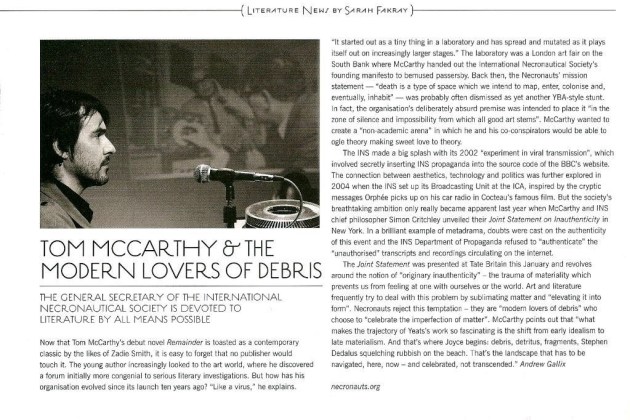

La lista es interminable y suena francamente bien. Noah Cicero (novelista estadounidense a medio camino entre Samuel Beckett y The Clash), Ben Myers (autor inglés mezcla de Richard Brautigan con Lester Bangs), Adelle Stripe (poeta londinense heredera del cinematográfico “realismo de fregadero” de Sidney Lumet), el propio Andrew Gallix (el Rimbaud de la Red), Tom McCarthy (novelista estadounidense afanado en la deconstrucción de una nueva idea de novela), HP Tinker (joven inglés al que comparan con Pynchon y Barthelme), Tao Lin (el aventajado protegido de Miranda July –a quien pronto veremos publicada en nuestro país gracias a Seix Barral-, con todo lo que eso supone hoy en día) y los primeros (parece que las grandes editoriales empiezan a tomar apuntes) que aterrizarán en España: Chris Killen, cuya novela “The Bird Room” será publicada este año por Alfabia, y Heidi James y Tony O’Neill, ambos con la editorial El Tercer Nombre.

Todos ellos influidos por el particular lirismo de Tom Waits, Lou Reed, Scott Walker o David Bowie, de la misma manera que estos sintieron la influencia de los autores de los que la Generación Offbeat es heredera. Aunque también están los que prefieren huir de las comparaciones. Tal es el caso de Heidi James, para quien la comparación es un poco “perezosa, basada en el hecho de que evitamos formar parte de la corriente principal”. Esta joven autora británica, que en marzo publicará su primera novela en España (“Carbono”, Ed. El Tercer Nombre) y que se confiesa fascinada por Lynne Tillman, Clarice Lispector, Marie Darrieussecq, Angela Carter o Virginia Woolf, es dueña de su propia editorial en Reino Unido, Social Disease. Con ella, que debe su nombre a la famosa frase de Andy Warhol -“Tengo una enfermedad social. Tengo que salir todas las noches”-, Heidi se ha convertido en uno de los estandartes de la Generación Offbeat al publicar “literatura única y genuina al margen de su valor en el mercado”.

Un movimiento coordinado

La propia Heidi James, en una prueba evidente de que el movimiento está coordinado y sabe hacia dónde se dirige, ha publicado en Reino Unido a autores como HP Tinker o Lee Rourke pero, sobre todo, a Tony O’Neill, el máximo exponente de los offbeats. Este joven neoyorquino, devoto de Bukowski, responsable de una prosa brutalmente descarnada, ex heroinómano, miembro de bandas como The Brian Jonestown Massacre, ha publicado ya cuatro novelas (la última, “Colgados en Murder Mile”, llegará a España en primavera) y se erige en líder (sin pretenderlo) del movimiento con ansias de seguir reclutando adeptos.

Como su propio nombre (offbeat) indica, una generación extraña e inusual de escritores, para los que la Red es su campo de acción, con espíritu punk y ganas de comerse la industria literaria tal y como ahora está concebida. El mundo anglosajón ya ha sido testigo de los primeros bocados. En España está al caer, ¡y ni siquiera es una generación! Que tiemble Zafón.