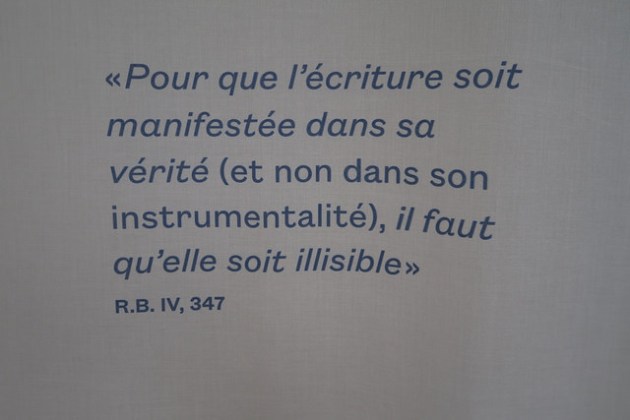

Roland Barthes, “Masson’s Semiography” (1973), The Responsibility of Forms (1982; 1985 in English)

For writing to be manifest in its truth (and not in its instrumentality) it must be illegible.

Roland Barthes, “Masson’s Semiography” (1973), The Responsibility of Forms (1982; 1985 in English)

For writing to be manifest in its truth (and not in its instrumentality) it must be illegible.

This piece appeared in Bomb Magazine on 4 June 2015:

David Winters by Andrew Gallix

“It seems to me that style becomes a kind of crucible—an acid bath in which the self is broken down, producing something unique, something new.”

Robert Musil regretted publishing the first volumes of The Man Without Qualities due to “the fixity they imposed on his ever-evolving work.” Similar misgivings almost led David Winters to shelve his debut collection of essays, from which the above quote is lifted. In conversation, the young English critic is given to qualifying—and even disavowing—past pronouncements, always returning them, with academic precision, to their rightful contexts. He is loath to see his provisional reflections turned into eternal truths, and wary of being co-opted by some dogmatic school or other. Infinite Fictions (Zero Books, 2015) is thus a snapshot of the author’s state of thinking over the last couple of years: a work in progress frozen in time.

Spurning any fixed theoretical position, Winters strives to preserve in his own essays the indeterminacy that lies at the heart—but also on the smudged margins—of literature. Given that the novels he writes about resist summation or translation, he has developed a contrarian brand of criticism that gestures towards what radically escapes it.

The enigmatic title derives from a conversation with Gordon Lish, whose “complex and compelling philosophy of literary form” looms large in these pages. Put simply, it refers to the intuition that fiction may “open up worlds which briefly exceed the limitations of life.” However, the book as “bounded infinity” cannot be construed as “an object of absolute sanctity”: it is always more than the sum of its parts. In this spirit, Winters wonders if “the words on the page” are really “worth as much as we think” compared with the “constellation of images” evoked by Andrzej Stasiuk’s Dukla. Apropos of Gerald Murnane’s Barley Patch, he goes one step further, contending that “the content of a work exceeds whatever words are read or written.” This excess—what is read into by the reader, or indeed the author—“both is and is not ‘inside’ the work.” Lydia Davis’s The End of the Story perfectly illustrates this reconfiguration of the parameters of the book by retaining “an internal relation to an idealized, unwritten other.” Winters is finely attuned to the unheard melodies of that “unwritten other” and, more generally, to the occult—allusive, subtextual, gestural—dimensions of literature. He even argues that “language is ‘literary’ whenever it interacts with its implicature.” Works of fiction are never approached as though they were written in stone, but as liminal spaces “blurred on both sides” by the writing and reading processes. In an interview with Evan Lavender-Smith, he points out that “real reading” (and I think this can be extended to real writing) “is rife with the imperfections of living.” Here, he wonders if literature is not, precisely, “this drift, these errors and excesses that are engrained in our reading experience.” These are some of the reasons why David Winters is probably the most vital critic in the English language right now. There are many others.

Andrew Gallix: Walter Pater famously declared: “All art constantly aspires towards the condition of music.” And this is certainly the case of the works you seem most attracted to. The experience of reading Christine Schutt—whose prose encrypts meaning “in rhythms and melodies”—is compared with that of “listening to music.” While Schutt should be “read reverently aloud” because her “poetic sentences speak of the things they can’t say,” we learn, in another chapter of your book, that Dawn Raffel uses this very same method, à la Flaubert, to compose sentences which “sing of the things that speech alone can’t express.” Time and again, you observe this transmutation of speech into song, whereby style merges with substance; form becomes inseparable from content. This kind of fiction—to quote Beckett on Joyce—is no longer “about something; it is that something itself.” Such novels or stories are untranslatable. They exist on their own terms, like Lish’s Peru, whose “truth lies not in its correspondence to reality, but in its consistency with itself.” You begin your piece on Jason Schwartz’s John the Posthumous by conceding that it is “impossible to synopsize.” This critical impasse leads you to focus as much on your “reading experience” as on the books “under review”—which brings us back to Pater. The author of The Renaissance argued that experience—not “the fruit of experience”—was an end in itself, thus initiating a redefinition of art as the experience of life. Is there some kind of lineage here?

David Winters: I’ll start with “music.” Yes, for me, cadence is everything. I’ve always been drawn to writing written, as William Gass puts it, “by the mouth, for the ear”—writing in which every phoneme counts; where prosody and acoustical patterning constitute a kind of thinking, a kind of cognition. For Pater, music collapses the opposition between subject matter and form—and so, in a sense, do the writers I write about. I’m not an uncritical disciple of Pater, but I do think the phrase “art for art’s sake” retains some residual value, insofar as it serves, in George Steiner’s words, as “a tactical slogan, a necessary rebellion against philistine didacticism and political control.” For instance, an acquaintance of mine once attacked the art I admire as a “triumph of style over substance.” I’d side with Pater in seeing such triumphs as a desirable “obliteration” of the distinction between “form and matter.” I’d follow him, too, in wanting to view the aesthetic object as extra-moral, or at least anti-ideological; an alternate world in which, as he observes in his essay on Botticelli, “men take no side in great conflicts, and decide no great causes, and make great refusals.” For me, part of the power of art lies in precisely those refusals.

Of course, what’s interesting about the passage you quote is the way in which Pater’s own writing obliterates, at a phenomenological level, the distinction between the artwork and what he calls “the moment”—a collapse that, as you say, returns us to “the experience of life.” I don’t mind admitting that I care very little about ethics or politics when it comes to art, and that criticism, for me—considered as a way of thinking through, or working with, works of art—is largely an attempt to live within and learn from that collapse. You mentioned my attraction to novels and stories that seem to resist explication. It’s true I find those kinds of texts more conducive to this experience; strangely, I feel that their closure creates an opening. For me, those works that appear the most self-enclosed—which seem to speak to themselves, like Schwartz’s, in a private language—are paradoxically the most enriching, the most alive. In a way, I feel like they’re more alive than I am. They don’t merely reflect the life I already know; they live lives of their own, and they invite me to change mine.

AG: Silence is a corollary of the quasi-alchemical process through which the words of the tribe—to reprise Mallarmé’s famous phrase—are purified into song. Let me quote a few examples from your book. Miranda Mellis’s The Spokes is “a story submerged in its own situation, such that a silence washes over it.” Jason Schwartz’s John the Posthumous “speaks in a style that startles the surrounding world into silence.” Dylan Nice’s stories “stage a world before which we can only fall silent.” This silence—which drowns out the white noise of the world, allowing the music of language to be heard—emanates from the radical irreducibility of such works, the self-enclosure you have just mentioned. Micheline Aharonian Marcom’s novels, like many of the books reviewed here, “could only have been written the way they are written,” and are thus resistant to criticism or any discourse “other than their own.” They illustrate the “flight from interpretation” that Susan Sontag had already observed in serious art, back in the late ’60s. Precluding hermeneutics, these fictions must be accepted on their own—alienating—terms. Schwartz’s is an art “that enfolds us in incomprehension.” The “very style” of Raffel’s stories “evokes an experience of unknowing.” You also praise Gabriel Josipovici, in Hotel Andromeda, for never attempting to encase Joseph Cornell’s art in “the amber of comprehension.”

Peter Markus recently told The Brooklyn Rail that what he looks for in a book is not meaning but that “state of awe which can leave us with its own kind of silence.” This put me in mind of what you once said in another interview: “Really, when I’m reading, all I want is to stand amazed in front of an unknown object at odds with the world.” Is the role of the critic to express this amazement in front of the mystery of literature?

DW: That’s what I’ve found myself doing in some of my reviews. It’s not at all what I do in my academic work, but reviewing allows for a different form of engagement—a more instinctive response. That said, I wouldn’t want to make normative statements on the basis of my private “amazement.” I simply want to write about artworks that move me. I have little to say about the “role of the critic”—a phrase that makes me squirm with suspicion. Critics are parasites; let’s not inflate our importance. Other critics can talk about roles if they like, or try to impose them on each other. If you’re going to give yourself over to the object, a role is really the last thing you want.

You mention Peter Markus, a remarkable writer whose work I’ve been following for several years. In that interview, Markus presents us with the figure of the witch doctor—the shaman who draws a circle in the sand, and then puts his sacred objects into play. It doesn’t matter what those objects are—a feather, a stone, a skull—ultimately, all the witch doctor wants is to fixate your gaze, to captivate your attention. For some of us, that’s what art is. I’m not sure how this relates to what Mallarmé wrote, but my position would be that if art purifies the language of the tribe, it does not do so for the tribe. The kind of art I admire makes its own language. Inside that circle, all that matters is the object in motion. If you really know how to write, how to paint, how to play your instrument, what you are doing is using that motion to create a structure with an internal consistency. You’re articulating a counter-language, whose purpose is not to purify but to stupefy—something which points away from the tribe. Art is not a social act; it’s an anti-social act. To be honest, if I were an artist, my aim would be to lead the tribe off the edge of the cliff.

A more literal way of putting this would be to say that the artworks I admire—the only kind I want to write about—are not interrogatives but declaratives. This kind of artwork is not a puzzle to be solved, and its role is not to reflect your existing knowledge back at you. Incidentally, this might be why I have so little respect for writers who make a show of alluding to philosophers in their work. The work itself should form a locus of philosophical force. As Wittgenstein says, “philosophy ought really to be written only as poetic composition.” In that sense, there’s more philosophy in a single sentence of Jason Schwartz—in the poetry of his syntax—than there is in… Well, I won’t name names. Let’s just say that Schwartz isn’t out to make anyone feel clever. The pleasure of “getting the references” is pretty much incompatible with the experience I’ve tried to describe. I’m not interested in books that invite self-satisfied comprehension. Like any serious reader, I’m looking for the real thing. And, for my part, I only know that I’ve found it when it defeats me. In my experience, criticism is at its best when it begins from a position of defeat.

AG: A recurring theme in Infinite Fictions is the danger of conflating reading fiction with knowledge—the rejection of information in favor of the unresolved, indeterminate, and auratic. At one point, you quote Gordon Lish’s definition of the writer’s job: “not to know what you are going to find.” This, of course, is reminiscent of Donald Barthelme’s famous 1987 essay, “Not-Knowing,” in which a writer is characterized as “one, who embarking upon a task, does not know what to do.” Barthelme goes on to claim that the “not-knowing is crucial to art, is what permits art to be made.” I wonder if this kind of negative capability is not also what permits your criticism to be made. And perhaps this not-knowing could be opposed to—or at least contrasted with—the knowledge that a work of fiction itself may harbor?

DW: You’re right. Lish and Barthelme do overlap on this issue, though Lish has something more precise in mind—an improvisatory poetics of the sentence, which proceeds by means of linguistic recursion. It’s a meticulous, syntactical version of negative capability, marked by profound epistemic uncertainty and insecurity. I’ve already written about that at length, as has one of Lish’s few really astute readers, Jason Lucarelli. Of course, Lish and Barthelme are both describing the creative act, not the critical act. The only “not-knowing” at work in my writing is of a much more familiar sort—the fact that putting thoughts into words brings forth new thoughts; Forster’s “how can I know what I think until I see what I say?”

Writing reviews, I tend to feel that I know nothing, and that my object knows everything. Reviewing a book like Stasiuk’s Dukla, for instance, all I’m doing is trying to cling to the contours, or the outline, of the object’s knowledge. In the last five or six years, perhaps the two books of criticism I’ve returned to the most have been Michael Wood’s Literature and the Taste of Knowledge, and, in relation to that, Peter de Bolla’s Art Matters. De Bolla brilliantly describes how questions of intention and hermeneutics give way, within the aesthetic encounter, to a more primordial problem: “the insistent murmur of great art, the nagging thought that the work holds something to itself, contains something that in the final analysis remains untouchable, unknowable.”

If I can return to the misuse of philosophy in fiction—that is, to novelists who engage in overt philosophical posturing—I suppose my disappointment stems from my feeling that great works of art only murmur their knowledge, whereas the worst ones seem to want to parade it. Back in the ’70s, Lish observed of Stanley Crawford that, reading his work, “one senses the pressure of having read all that’s to be read without trying to give evidence of erudition.” That sense of pressure is what I’m after. That’s why Wittgenstein disliked Tolstoy’s more didactic works; as he wrote in a letter to Norman Malcolm, “when Tolstoy turns his back to the reader, then he seems to me most impressive. His philosophy is most true when it’s latent in the story.” Cora Diamond’s gloss on that letter stresses the sense in which, for Wittgenstein, philosophy should be “contained in the work, but not by being spoken of, not by being told.”

I’d say it’s the same with the question of art and knowledge. Take Gerhard Richter’s painting, Betty (1988). Or Velasquez’s Las Meninas. In each case, the composition is organized in such a way that the perspectival structure forces a deviation of the spectator’s attention. That’s what a lot of the artworks I work on are doing. That’s what, say, Schwartz is doing. Like Richter’s Betty, Schwartz’s work has its back turned. Like her, his language is looking at something I can’t see; it knows something I’ll never know. It’s incredible, as a critic, to encounter an artwork like that. A work that radically alters the parameters of critical practice. Confronted with this kind of object, the task is no longer to try to uncover art’s knowledge, but rather to follow its gaze.

AG: Just as Betty, in Richter’s painting, turns her back on us, writing, in your view, says “‘no’ to the world.” Asserting “its agon against all that is,” the novel is fundamentally “at odds with the world.” You have even claimed, quoting Michel Houellebecq, that literature is literary “insofar as it is, in itself, ‘against the world, against life.’” Could you talk about this?

DW: Seeing those quotes out of context, I feel like prefacing each one with “the kind of writing I like” or “the books that interest me,” or perhaps some longer prevarication: book x happens to move me insofar as I feel, subjectively, that it possesses quality y. Always, I’m writing about my experience of being with a particular artwork, and statements like these belong only to that experience.

You’re right, though. For me, being in the presence of works of art basically means not being in the world. I guess this stems from what I’ll reluctantly call my “religious” temperament—reluctantly since, as Salinger says in Franny and Zooey, any allusions to “God” will rightly be interpreted as “the worst kind of name-dropping, and a sure sign that I’m going straight to the dogs.” To indulge in some marginally less embarrassing name-dropping, maybe it matters that when I was younger, I was obsessed with the likes of Meister Eckhart, Pseudo-Dionysius, The Cloud of Unknowing. Plotinus was important to me. Hans Jonas’s work on Gnosticism was equally important. And Beckett, of course—especially Ill Seen Ill Said, which, back then, I read as John Calder does: he calls it “the last chapter of the bible”—a kind of creation myth in reverse. I don’t read Beckett in quite the same way today, and I doubt I understood Plotinus anyway. All the same, it’d be fair to say that my personal ontology has always been a kind of Gnostic acosmism. Some things are too deep-rooted to change.

That remark about art’s “agon against all that is” comes from my review of Lish’s novel about violence and memory, Peru. The point of that review was not to make hyperbolic claims about all works of art, but rather to try to describe the way in which a particular work secures for itself a kind of “truth.” On the surface, saying that art “says no to the world” simply sounds nihilistic. But Peru only says “no” in order to make a world of its own. To be more precise, I believe that the book brings about a kind of “world-making,” in the philosopher Nelson Goodman’s sense. And I believe that the stability of the world it creates is proportional to the force with which it negates the given world. Peru, like several of the books I’ve written about, is almost like a pocket of negative entropy—a bubble in which the arrow of time is reversed. A cosmos whose inner stability is not less than, nor continuous with, that of our own. This kind of artwork isn’t unlike Tarkovsky’s “Zone”—a magic circle, inside which objects obey their own laws of motion.

So, I see the artist as almost an alter deus; a bricoleur who builds a blasphemous world. What attracts me to certain of these worlds is their ability to exert a peculiar counter-pressure; an equal and opposite force to that of what we call “reality” (this is what Adorno, in Aesthetic Theory, calls art’s “opposition to mere being”). If you consider the physics of that, perhaps opposition is only part of the picture: some other requirements might include proportionality, self-similarity, self-sufficiency. Earlier, you quoted me saying that Peru’s “truth lies not in its correspondence with reality, but in its consistency with itself.” When I talk about art’s antinomian oddness or wrongness—its being “at odds with the world”—I’m describing its capacity to define its own “truth,” through cohesion, not correspondence. As Goodman puts it, “more venerable than either utility or credibility as definitive of truth is coherence, interpreted in various ways but always requiring consistency.”

AG: “The world, as Wittgenstein says, is everything that is the case. But writing is whatever is not.”

DW: I said that during a roundtable conversation on style in fiction, published in The Literarian the year before last. Rather than repeat my response to your last question, I’ll answer with another quote, drawn not from my writing, but (since we discussed Pater earlier) from Denis Donoghue’s landmark study, Walter Pater: Lover of Strange Souls. Donoghue is listing the family resemblances between different versions of aestheticism, of which Pater’s is one. These are the principles he extracts:

A work of art is an object added to the world. Its relation to the world is not that of an adjective to the noun it qualifies. The relation is more likely to be utopian than referential. Art is art because it is not nature. In an achieved work of art we find a certain light we should seek in vain upon anything real. The work does not take any civic responsibility; it does not accept the jurisdiction of metaphysics, religion, morality, politics, or any public institution.

Donoghue notes that these notions are nowadays “often derided,” but then maintains, “I don’t deride them.” Neither do I, and I would side with his desire for a critical stance that preserves the artwork from what he calls “the rough strife of ideologues.” As he puts it, “the world proceeds by force of its chiefly mundane interests; it is an exercise of power and of responding to the power of others. Meanwhile we have literature, and the best way of reading it is by putting in parentheses, for the duration of the reading, the claims the world makes upon us. There will be time for those to assert themselves.” To rephrase your quote: art makes its own time, inside those parentheses.

AG: I would like to return to the idea of absenting oneself in the presence of art—that experience of “ego-loss” you seek through reading, and once described in quasi-mystical terms as a “miraculous disappearance.” In the introduction to Infinite Fictions, you explain that reviewing allows you to explore “the space left by [your] subtraction”—a beautiful phrase I simply had to quote. Does literature provide us with an intimation of the world-in-itself, or at least the world-without-us?

DW: The question reminds me of a passage in Dukla, where Stasiuk depicts an “unpeopled” landscape, containing only inanimate objects. “This must have been what the world looked like before it was set in motion,” he writes; “like a stage set on which something was going to take place only later, or else already had.” Similar feelings are elicited by some of De Chirico’s landscapes. For me, though, the “subtraction” you mention is best captured by the art historian Joseph Koerner, describing one of Caspar David Friedrich’s rückenfiguren. Much as we discussed earlier, Friedrich’s figures stand with their backs turned to the spectator, gazing away from us, into the canvas. Confronted with one of these images, Koerner writes: “I do not stand at the threshold where the scene opens up, but at the point of exclusion, where the world stands complete without me.”

When I pick up a book, I’m in pursuit of that point of exclusion. I’m forever in flight from myself, and I find that books briefly allow me a form of forgetting. I’ve no idea whether fiction has any connection to the world “in itself.” What I mean by “subtraction” is more like a fleeting illusion of weightlessness; a sense of suspension which lasts as long as the artwork allows it. That’s the relief of reading, for me—although I think that it also applies to the act of writing. I do view creativity as a kind of vanishing act—an escape from ipseity. As an aside, perhaps this explains my distaste for personal essays, memoirs, and the like—not to mention my ambivalence about social media. In our current culture of narcissism, we might all benefit from a little ego-destruction.

AG: Absolutely! However, as you write at the outset of your book, “In reading we disappear, and yet we resurface.” Please talk us through the apparent paradox of this “dual movement.”

DW: Like I said, the illusion lasts only as long as the artwork allows it. None of us ever really escape from ourselves, but we can hope for flashes of insight into what it might be like. Over the course of our lives, our fates are shaped by the choices we make; we create labyrinths in which we are cornered and caught. That’s the great intuition of Greek tragedy, of course: “Creon is not your downfall, no, you are your own.” From day to day, we don’t feel ourselves falling, just as we don’t feel the gravity beneath our feet. But what we perceive as unimpeded motion is, in the end, a plummet towards an object whose pull we cannot evade. By now, you’ll have picked up on my unease at being confronted with quotes from my writing. Well, that’s the same; hearing my speech spoken back at me feels like being trapped, left looking into the eyes of my corpse. My sense of my published writing resembles my sense of my life: a dossier of evidence I’ve clumsily compiled against myself. By contrast, I take the view that what art can do is avert my eyes from where they would otherwise come to rest. Or, to put it another way, art enables a brief deviation from the earth’s gravitational pull. Clearly, aesthetic experience is as transitory as anything else: when we read or write, or watch a film, or listen to music, the clock is still ticking. The paradox, though, is that this type of attention seems to create a time of its own—a continuum which runs against the time of the clock. An image, or mirage, of infinitude can sometimes be found in those moments, although it is bounded, and always brought back to the finite. Simply put, the dream of art ends, and then we wake up.

AG: There seems to be a tension, in your work, between the impersonal (the aforementioned desire to “escape from ipseity” into self-sufficient fictive worlds, for instance) and the personal (your interest in the “psychic life” of writing, your conception of style as “the site of intersection with life,” or refusal to isolate theory from life). How do you account for this?

DW: The apparent tension is adequately accounted for by distinguishing the ego from the id; what we think we know of ourselves from what underlies and dismantles that knowledge. Adopting a more metaphysical tone, we might even want to distinguish the “self” from the “soul.” When I mention an “intersection” between style and life, I don’t mean to define style as an extension of the writer’s ego. I’m not remotely interested in style as an assertion of the self; I’m interested in style’s capacity to undermine the self, or to uncover a secret self that even the writer might be afraid of. I believe that the best writers are utterly unraveled by their style, crucified by their style.

For instance, you and I are both longstanding readers of Gary Lutz. If you look closely at Lutz’s style—which is, by design, the only way one can look at it—maybe you’ll see the same thing I see. Lutz’s writing reflects very little of his biography; instead it exposes something of his soul. Many writers today seem intent upon putting as much of the “self” as they can into the content of their prose. Lutz, on the other hand, injects his soul into the syntax of his stories, the intervals between his syllables, the signature of his style. This kind of writing does not project or preserve the ego; it controverts and collapses the ego. With a writer of Lutz’s caliber, it seems to me that style becomes a kind of crucible—an acid bath in which the self is broken down, producing something unique, something new.

Speaking more broadly, my stance on style isn’t all that unlike Susan Sontag’s. I’d side with her in seeing art’s content as an occasion for form; “the lure which engages consciousness in formal processes of transformation.” Sontag’s mention of transformation also reminds me of Alain Badiou’s account of the golden age of French theory. For Badiou, the unifying feature of French philosophy in the 1960s was that its principal players were “bent upon finding a style of their own; a new way of creating prose.” Crucially though, their search for a style was far from simply stylistic. As Badiou says, “at stake, finally, in this invention of a new writing, is the enunciation of a new subject.” In fiction, as in philosophy, any invention of a new style enunciates a new subject-position—a particular way of being, potentially at odds with those which already exist. I wouldn’t attribute to style the political valence that Badiou might attribute to it, but I would say this: the kind of writing I admire doesn’t reproduce a person’s life; instead it suggests entirely new forms of life.

AG: You have described Diane Williams as “a writer I lack the skill to review.” What are those skills you allegedly lack?

DW: A less coy way of putting it would be to admit that I’m neurotically conscious of what the critic Cleanth Brooks called the “heresy of paraphrase”—the reduction of the experience of a poem to a statement about that experience, or an abstraction from it. Williams’s art seems to me the most accomplished, the most audacious, in its evasion of that type of explication. In a sense, it’s precisely the kind of art I’m looking for—but also, by that definition, the kind I’m most afraid to find. I’ve tried to write about it, of course, but it undoes me every time. Probably the best way to write about Williams would be to spend some time writing only about paintings, or only about music, and approach her compositions from that angle. I’m not sure the resources of literary criticism are quite adequate, in her case. That said, I believe she’ll have a new book out before too long—so, having dug myself into this hole, I hereby commit myself to writing a review.

You are now one of the foremost authorities on Gordon Lish, whose presence looms large in Infinite Fictions as well as this interview. How important is his own work compared with his impact as an editor or a creative-writing guru?

Alongside Max Perkins, Lish is one of the two most important American editors of the twentieth century. Nonetheless, I would argue that the historical significance of his teaching outweighs even that of his editing. The precise nature of that significance will take many years to become clear; half a century’s accumulated hype, rumor, and bullshit must first be washed away. My advice, on this score, would be to ignore anything that journalists, bandwagon-jumpers, or self-appointed biographers might say; the only people equipped with an accurate picture of Lish’s teaching are those who meaningfully studied with him. And by that, I don’t mean people who took a couple of classes, dropped out, and wrote magazine articles about their experience—I mean those who stayed the course and emerged to produce original work. Originality being the essential point: as I understand it, Lish intended his teaching as a ladder to be climbed and then cast aside. In the end, it’s really no different from Emerson’s dictum: “never imitate.”

As for Lish’s fiction, conventional wisdom would say that it’s less successful than that of the authors he’s influenced. I’ve read all of it now, from beginning to end and back again. Even so, I’m only just beginning to grasp it. Lish’s prose requires extraordinary attention and concentration. Actually, part of what he’s doing is revising the structure of attention—reconfiguring the reader’s gaze. I only understood that after I’d spent a great deal of time in his presence, on the page. One difficulty is that Lish is recklessly uncompromising in his struggle against conventional effects, against imitation. Certainly, there is a willful astringency to his style. Another problem is that he’s looking at his native language from a new angle—a perspective which appears to distort that language, but which paradoxically clarifies its creative capacity, its “grammar.” Above all, Lish isn’t writing with the market—or maybe even the present—in mind. In a way, his work enacts a kind of wager, a high-stakes bet that the value of art will be proportionate to its untimeliness. In fifty years’ time, will Peru finally be recognized as one of the masterpieces of modern American literature? Will Epigraph? Will Extravaganza? I don’t know, but I daresay they’ll prove more enduring than the facile efforts of Franzen and co.

AG: Significantly, your first publication was a review of Roland Barthes’s The Preparation of the Novel—a series of lectures that the French critic conducted as if he were going to compose a work of fiction. It appears that reviewing allowed you, contrarily, to proceed as if you were not going to write a novel. In that seminal review, you observe that the novel “exists in the mind of its reader less as a literary object than a wish underwritten by other wishes.” Was it this realization that allowed you to embrace criticism without being—like so many other reviewers—a frustrated novelist? Do you envisage a return to fiction at some stage?

Writing a novel is almost a universal fantasy, isn’t it? Although, for most of us, the fantasy is not really of writing a novel, but only of having written one, and of it being read. In this respect, the fantasy of the novel is partly a fantasy of communication, or recognition (the dream of finally saying all of the things you desired, but failed, to say—and thereby revealing the “real” you) and partly one of immortality, or at least remembrance (the dream of your novel “living on” after you’ve gone). The truth is that when I wrote that piece about Barthes, I was writing a novel. I knew, though, that what I was writing came closer to fantasy than reality. So, I started writing reviews in order to free myself from that fantasy. I wouldn’t rule out a return to writing fiction some time in the future, but if I did, you wouldn’t know it was me. Pseudonymity always struck me as the only appropriate mode for creative writing. I’m on the side of Pessoa, hiding The Book of Disquiet away in a trunk—not that hack Knausgaard, passing off narcissism as art. Whenever I’ve dreamt of writing a novel, I’ve dreamt of writing it with a new name.

AG: In the introduction to Infinite Fictions, you acknowledge that “to write a review is to hide behind what another, better writer has written.” Throwing humility overboard, could not we also argue that the aim of criticism is to see the object as it really is not—to see it as it could or should be, perhaps even as it sees itself? In fact, could not we even argue that literature is a by-product of criticism—that criticism uses fiction as its raw material to dream literature into existence?

DW: I’m rather reluctant to throw humility overboard; there’s not nearly enough of it among literary critics. This is tangential to your question, but I’d like to reiterate my opposition, which I’ve aired elsewhere, to what John Guillory has called the “fantasy of literary power.” Guillory’s phrase refers to the presupposition, revealingly common to critics, that “literary culture is the site at which the most socially important beliefs and attitudes are produced.” Just as I’m skeptical of critics who reduce texts to reflections of social conjunctures, I’m equally unconvinced by those who treat literature as a “site of resistance” to those conjunctures. As Mark McGurl has observed, such gestures tend to lend literature “a dignity of effective scale that it does not necessarily deserve.”

If we discard those fantasies, then “seeing the object” must obviously be our aim. In that case, though, the question becomes: what kind of seeing? Your own question alludes to Matthew Arnold’s call for critical objectivity in “The Function of Criticism at the Present Time” and to Wilde’s parodic inversion of Arnold in “The Critic as Artist.” Wilde has one of his characters claim that “to the critic, the work of art is simply a suggestion for a new work of his own, that need not necessarily bear any obvious resemblance to the thing it criticizes.” Against Arnold’s order to “see the object as it really is,” Wilde’s character asks us to “see the object as it really is not.” I wouldn’t go quite that far, but I would probably agree with Pater’s more subtle modification, according to which the aim of critical appreciation is “to see one’s impression as it really is, to discriminate it, to realize it distinctly.”

Of course, no one ever sees the object as it really is. That’s true of critics and artists alike, insofar as artistic practice is also an effort to render an object. As you know, I take the view that art’s objects are infinite. To my mind, an accomplished work of art is one that attempts to see its object from every angle—apprehending every aspect, every stratum, every extension. In their own ways, that’s what Gertrude Stein does, what Thomas Bernhard does, what Gordon Lish does. The object, however, can never be mastered, and failure is always the outcome. Critics and artists are the same, in that sense: all we can really control is the scope, the shape, the originality of our acts of failure. Like the artist, the critic confronts an impossible object—one which, as certain philosophers say, withdraws from the world around it. We look at our objects, as long as we can, but no way of looking will fix them in a final form. So, like the artist, the critic must endlessly circle the object, looking for new ways of seeing. This, by the way, is why dogmas and doctrines are the death of critical practice—to see the object from a single position isn’t to see it at all. So, for me, the goal—or perhaps the obligation—of criticism closely resembles that of art: the continuous cultivation of perception, the invention and re-invention of the gaze, and the search for new modes of attention. Earlier, you asked me about the “role of the critic.” I think this is all I’m able to say: the critic must always keep looking, and never stand still.

Jean-Philippe Toussaint, Urgency and Patience

With this preparatory phase carried to its extremity, the danger lies in never starting the novel (Barthes’ syndrome, in a way), like the narrator of Television who, due to exaggerated scruples and anxiety from the exigencies of perfectionism, settles for a constant state of readiness to write “without taking the easy way out and actually doing so”.

My interview with Simon Critchley appeared in 3:AM Magazine on 3 December 2014:

Writing Outside Philosophy: An Interview with Simon Critchley

3:AM: Do you agree that much of your back catalogue can now be read as a preemptive commentary on Memory Theatre, as though the latter had been written in the stars all along (which would be in keeping with the book’s uncanny astrological theme)?

SC: Sure. Why not? Look, what I really learned from Paul De Man years and years ago was that writers are structurally self-deceived about what they do, what they write and the intentions that might or might not lie behind their writing. Namely, to write is to be blind to one’s insight, if such insight exists. I understand this structurally: namely, that writing is an adventure in self-deception. I simply do not know what I am doing and you — as a reader, and a very good reader, moreover — can tell me what I am doing much more accurately than I can. Therefore, I should be interviewing you. In fact, let’s consider that we have reversed roles.

3:AM: The late Michel Haar, who haunts the book, is said to have been fascinated by the “poetic dimension” of Nietzsche’s style, which he saw as “that which might escape philosophy” — a fascination you also share. In Very Little . . . Almost Nothing (1997), you argued that “Writing outside philosophy means ceasing to be fascinated with the circular figure of the Book, the en-cyclo-paedia of philosophical science, itself dominated by the figures of unity and totality, which would attempt to master death and complete meaning by letting nothing fall outside of its closure”. Did you need to exorcise your fascination with this totalising tradition — by dramatising its failure — in order to write “outside philosophy”?

SC: Wow, thanks for reminding me of that passage from Very Little . . . Almost Nothing, which was written in 1992 or 93, as I recall, right towards the beginning of what became that odd book. I have two contradictory reactions to your question: on the one hand, many of the authors I have been obsessed with over the years have endeavoured to take a step outside philosophy, by which is usually meant the circle and circuit of Hegel’s system or Heidegger’s understanding of history as the history of being. I respect and love that gesture, that can be found in Bataille, Levinas, Blanchot and others. But, on the other hand, what I learned from Derrida very early on — my master’s thesis was on the question of whether we could overcome metaphysics — is that the step outside philosophy always falls back within the orbit of that which it tries to exceed. Not to philosophize is still to philosophize. Similarly, any text or philosophy that simply asserts the value of metaphysics is internally dislocated against itself, undermining its own founding gesture. This leaves us writing on the margin between the inside and the ouside of philosophy, which is where I’d like to place Memory Theatre. Also note that although Michel Haar existed and was real, as it were, he didn’t say much or anything that I say that he said. He is a kind of vehicle that I try and drive and steer.

3:AM: At one time, you entertained the idea of writing a book entitled “Paraphilosophy”, devoted to philosophically-impossible objects. A memory theatre strikes me as an impossible object of a different kind: one that can be conceived of, yet never conceived. Is your work a critique of what you call elsewhere the “aestheticization of existence” — the avant-garde project of turning life into art?

SC: Another way of answering your previous question would be to say that I am committed to a form of paraphilosophy, organized around what I call ‘impossible objects’ (a version of the scraps of that abandomed project will be published next year, I think). On the question of the aestheticization of existence, I sometimes really don’t know where I stand. On the one hand, we have known since Benjamin, that fascism aestheticizes politics, but on the other hand, much of what I do is committed to the idea of the aesthetic particularly as art practice as it was embodied in various avant-garde groups. Does that make me a fascist? Lord, I hope not. I think at that point we need to make a distinction between aestheticization in the tradition of the Gesamtkunstwerk and totality, the architecture of fascism, and that writing that unpicks, unravels and mocks that tradition of the Gesamtkunstwerk in the name of another practice of art, what Blanchot called the infinite conversation. It is in the spirit of the latter that I have tried to work.

3:AM: Memory Theatre includes a series of photographs — by British artist Liam Gillick — of a skyscraper in construction. Their appearance in reverse order (which reminded me of Robert Smithson’s notion of “ruins in reverse”) mirrors the deconstruction of the narrator’s attempt to build a real-life memory theatre. I wonder, however, if these pictures do not also refer to his surrogate grand narrative: a “perfect work of art” that would eventually “become life itself” by merging with it. One of the recurring themes in the book is that of the quest for a prelapsarian universal language which, although mocked by Swift, was once very fashionable: you write, for instance, of Leibniz’s “attempted recovery of the language of Adam against the Babel of the world”. Does Gillick’s dismantling of this Tower (block) of Babel gradually lead us towards an immanent conception of art that could express the world as it is in itself, free from human perception?

SC: Yes, but this is another fantasy: that of the artwork having an autonomy independent of its creator. A kind of machine or a puppet, or the fantasy of a non-human artwork, which is currently doing the rounds. All of this is in play in Memory Theatre for sure. What do Liam’s pictures suggest? To me, they exhibit a process of dismantling, or decomposition, that is ultimately the dismantling of philosophy and the decomposition of the heroic figure of the philosopher that has plagued us since Socrates. Memory Theatre is a critique of philosophy and, of course, a self-critique of my position as a ‘philosopher’. And yes Swift’s mocking of the science of his day, in Book III of Gulliver’s Travels has always been very important to me.

3:AM: Would you agree that the memory theatre and the “perfect work of art” envisioned at the end of the book correspond, respectively, to the two poles between which literature oscillates according to Maurice Blanchot? On the one hand, what you have called the “Hegelian-Sadistic” tradition, driven by the work of negation of human consciousness, and on the other, a striving after “that point of unconsciousness, where [literature] can somehow merge with the reality of things” (Very Little . . . Almost Nothing). Both poles, of course, are unattainable, but I suspect you have more sympathy for the latter, which is on the side of “The Plain Sense of Things” (Wallace Stevens) — “the near, the low, the common” (Thoreau) — and “lets us see particulars being various” (Memory Theatre) . . .

SC: That’s very interesting and I stole the “particulars being various” from Louis MacNiece, who is underrated and underread in my view. I remember reading Blanchot’s account of the two slopes of literature and it making a huge impact that continues to reverberate, particularly in relation to the INS [International Necronautical Society] work that I do with Tom McCarthy. On the one hand, literature is a conceptual machine that comprehends all that is, digests it and shits it out. That transforms matter into form. On the other hand, there is a kind of writing — poetry usually (Ponge, Stevens, late Hölderlin) — that attempts to let matter be matter without controlling or comprehending it. I am more sympathetic to the second slope, but the attempt to let matter be matter without form is also an unachievable fantasy. We can say with Stevens, we don’t need ideas about the thing, but the thing itself. But we are still stuck with ideas about the thing itself, with the materiality of matter. Form, even the form of the formless, is irreducible.

3:AM: Reviewers have remarked on the hybrid nature of Memory Theatre — a mixture of essay, memoir, and fiction. Why did you choose to call the narrator “Simon Critchley” — who is both you and not you — instead of creating a fictive character based on yourself? I’m guessing that you relished the ambiguity of inhabiting that gap between you and yourself (to paraphrase Pessoa) . . .

SC: The figure ‘Simon Critchley’ is a quasi-heteronym in Pessoa’s sense. You are absolutely right. I did have a lot of fun working in the gap between myself and myself, trying to create a kind of crack in myself, a decomposition as I said just now. ‘Simon Critchley’ is not me, but is still more than a little bit me. As for the hybrid nature of the text, all I can say is that this is how it came out. I wrote the first draft really quickly in about three weeks, largely against my will. It just came pouring out like that after I’d finished writing The Hamlet Doctrine with Jamieson Webster. Then I looked at Memory Theatre when it was done and was perplexed. What is that thing? I didn’t want to publish it. But other people liked it and I am stupidly vain.

3:AM: At one point your narrator believes he is about to discover his deathday, and feels “strangely exhilarated rather than afraid”: this episode echoes what Blanchot (or his protagonist) experiences, in The Instant of My Death, when he seems to be on the verge of being executed. The opposition between death and dying also derives from Blanchot (and Levinas), as does the example of suicide by hanging:

Even if I hanged myself I would not experience a nihilating leap into the abyss, but just the rope tying me tight, ever tighter, to the existence I wanted to leave (Memory Theatre).

Just as the man who is hanging himself, after kicking away the stool on which he stood, heading for the final shore, rather than feeling the leap which he is making into the void feels only the rope which holds him, held to the end, held more than ever, bound as he had never been before to the existence he would like to leave (Thomas the Obscure).

The image of the dredging machine is a clear reference to Derrida (referencing Genet). “The void has destroyed itself. Creation is its wound” is lifted verbatim from Georg Büchner’s Danton’s Death. “The blank, expressionless eyes of forty-nine papier mâché statues stared back at me” is possibly a nod to Hoffmannstahl’s “I felt like someone who had been locked into a garden full of eyeless statues” (The Lord Chandos Letter). I am sure that there are many other examples of references to, or quotations from, other people’s works that I missed or did not even recognise. Do you consider intertextuality — another aspect of the book’s hybrid nature — as a memory theatre?

SC: You are too good, Andrew, too good. Yes, I used all these quotations, usually from memory, in the text and there are many, many others. Memory Theatre is a kind of composite and composition drawn from everything that I have ever read and remembered. I then seek to decompose them, pull them apart, by setting them to work in some different way. Palimpsest-like. I have always been suspicious of ‘intertextuality’ as it sounds like a post-structuralist version of ‘tradition’. We are composed of networks of citations and references. At least I am. It’s the way I think about things most of the time.

3:AM: There are many instances of internal intertextuality (sorry!) in Memory Theatre, but most seem to come from your earlier works. Is this purely coincidental, or does a regressive theme run through the whole book? I’m thinking, for instance, of the narrator’s contention that Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit “can only be read in reverse” or his tentative description of his youthful memory loss as “a kind of reverse dementia”, not to mention Gillick’s pictures . . .

SC: Yes, there is a kind of inhabitation of all my earlier work in Memory Theatre. That was deliberate. It felt like a taking stock, a settling of accounts with myself. A look back into the rear-view mirror as I press harder on the gas. Also, to make matters worse, my first idea for a PhD thesis in 1987 was on Hegel’s conception of memory in relation to the tradition of the art of memory. So, Memory Theatre is also an attempt to write (and unwrite or undo) that original dissertation plan.

3:AM: When the memory theatre is built, ‘Simon Critchley’ surveys his work: “Like crazy Crusoe in his island cave out of his mind for fear of cannibals, I would sit onstage and inspect my artificial kingdom, my realm, my shrunken reál”. This reminded me of what Barthes writes about Jules Verne’s “self-sufficient cosmogony” — symbolised by The Nautilus (“the most desirable of caves”) — that he likens to “children’s passion for huts and tents”:

The archetype of this dream is this almost perfect novel: L’Ile mystérieuse, in which the manchild re-invents the world, fills it, closes it, shuts himself up in it, and crowns this encyclopaedic effort with the bourgeois posture of appropriation: slippers, pipe and fireside, while outside the storm, that is, the infinite, rages in vain (Mythologies).

One might also think of Georges Perec, who often circumscribed a small fragment of the world and then set about exhausting it. This dream of a total artwork in which one might poetically dwell often ends up being a womb with a view, right?

SC: Absolutely right. It is a kind of male, maternal fantasy. Except the child is always stillborn. It is also a meditation on obsessional neurosis and the masculine sexual tendency to collect, to collate and to kill. Memory Theatre describes a solitary and dead world devoid of love. I do not want to live in that world, though I have often found myself oddly at home in it. I hate myself. That much should be obvious.

3:AM: There seems to be a crisis of fiction today, highlighted by authors like David Shields or Knausgaard. Is Memory Theatre’s genre-bending a reflection of this crisis? Have we — writers and readers alike — lost that capacity to lose ourselves, which fiction, I feel, is premised on? Can disbelief no longer be suspended?

SC: Maybe we have lost the capacity to suspend disbelief because the world seems such a strange, malevolent fictional edifice. But I am against the heroic authenticity of memoir, the laying bare of oneself in what purports to be reality. I read a chunk of Knausgaard recently. It’s great, but it’s not for me. I’ve been to Norway too much for that. Memory Theatre is a kind of anti-memoir, perhaps even a kind of pastiche. I mean, someone wrote to me recently because they believed that everything I had said in Memory Theatre was true and they were truly worried about me. This was heartfelt and nice, but strange. I do not want to be the ‘Simon Critchley’ of Memory Theatre.

3:AM: Recently, Rachel Cusk claimed that “autobiography is increasingly the only form in all the arts” — and she may well have a point. This put me in mind of what you wrote, quoting Blanchot, in Very Little: “In the journal, the writer desires to remember himself as the person he is when he is not writing, ‘when he is alive and real, and not dying and without truth'”. Does this account for the autobiographical turn in literature and the arts?

SC: I don’t know, in the sense that I don’t have an opinion. I am always suspicious of ‘turns’ to anything. Literature is always autobiographical and it always isn’t just that. It requires research and reading. We have to simply face up to that contradiction. Literature is one long song of myself even when that self is something I really don’t want to be. In fiction, we step out of our skin, but we still remain in our skin as we read it.

3:AM: Has psychogeography partly inherited this tradition of the memory theatre (as the narrator seems to imply at one stage)?

SC: Yes, that was definitely on my mind at an early stage of thinking about the project. The idea of psychogeography as the construction of alternative maps for cities and places is what is at stake in Memory Theatre. I got that from Stewart Home. When the narrator wakes from the dream/nightmare of the Gothic cathedral in the middle of Memory Theatre, the entire landscape is psychogeograpized, legible through some arcane, occult grid.

3:AM: I’m pretty sure you must also have been thinking about the web — today’s version of the memory theatre — while writing the book. We live in an age of total recall and rampant dementia. It would be absurd to establish a connection between the two phenomena, but are we not increasingly relying on Google or Wikipedia to remember facts we would have memorised ourselves in earlier times? In other words, are we not using the web in order to forget?

SC: Yes, absolutely. Today’s memory theatre is the internet. I deliberately avoid broaching the question of the internet in Memory Theatre, but it’s what the whole thing is about. The difference — and it is crucial — between the internet and the memory theatre is the difference between Gedächtnis and Erinnerung, between an external, mechanized memory and an internal, living recollection. What has happened — largely without anyone noticing it — is that we have outsourced memory onto the internet. Everything is there, googleable, but not in our heads. Is this a good thing? I don’t know. It is certainly an odd thing, given that for several thousand years all education has ever meant has been the cultivation of a trained memory. We have somehow abandoned that in the name of forgetfulness. So, yes, we have chosen to drink the waters of Lethe and enter our private Hades. Literature can at the least remind us of that choice.

3:AM: Even though we are constantly (unwittingly) rewriting our own pasts, isn’t the right to be forgotten — which has arisen in the face of total digital recall — a rather dangerous concept? Are we really the sole owners of our pasts?

SC: No, we are not sole owners of our pasts. The drama of Memory Theatre is showing how our existence can be pre-remembered, as it were, by someone else, pre-destined. The fantasy of total recall, which is one way of approaching Hegel, is often met by the fantasy of active forgetting, in Nietzsche’s sense. Both these fantasies are delusional. We are flayed alive by memory, but not in possession of it.

3:AM: I was thinking of Proust’s notion of involuntary memory, and how In Search of Lost Time could be construed as a memory theatre, but what of the unconscious?

SC: Like I said earlier, Memory Theatre can be read as a case study in obsessional neurosis, as an attempt to collate, collect, control, and kill all that is and all that is close to you. I see the ‘moral’ of Memory Theatre in negative terms: do not build your memory theatre! That means trying to access unconscious material in other ways, in relation to other forms of sexuality than masculine obsessionality, and in relation to a different range of affects and transferential relations. This is a project I tried to begin with Jamieson Webster in The Hamlet Doctrine, a book of which I am really proud, mostly because I only-co-wrote it.

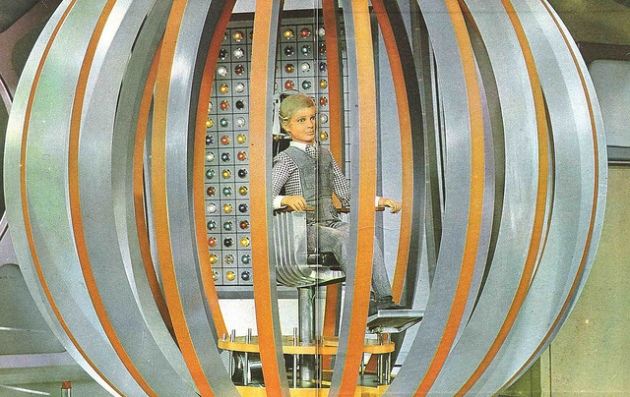

3:AM: Did Giulio Camillo Delminio’s memory theatre remind you, like me, of a similar contraption in 60s TV series Joe 90?

SC: Oh Lord, I used to love that show. I’d forgotten about it, as it were.

3:AM: The memory theatre tradition and dream of total recall find an echo in ‘Simon Critchley’ because (like you) he lost much of his memory following an accident (“My self felt like a theatre with no memory”). Accident-induced memory loss also happens to be the premise of Tom McCarthy’s Remainder. The quest for the “now of nows” — that moment of “absolute coincidence” with oneself and one’s fate at the point of extinction — is precisely what McCarthy’s anti-hero strives to achieve through his increasingly elaborate reenactments. As for the following sentence, it could come straight out of C: “My body is a buzzing antenna into which radio waves flooded from the entire cosmos. I was the living switchboard of the universe” . . . In Very Little . . . Almost Nothing, you pointed out that there is so much overlapping between Blanchot and Levinas that it is sometimes difficult to tell if an idea originated with the former or the latter. The very same comment could be made about you and McCarthy. Are you — especially through the International Necronautical Society — trying to escape the confines of the self by merging your two voices in a collaborative, polyphonic project? Is it two people, one artist, like Gilbert & George?

SC: Matters become even worse when you think of the first sentence of Remainder, which refers to Very Little . . . Almost Nothing. My relation with Tom is very precious to me and I have loved working together with him so much over the years. There is no doubt that meeting and working with Tom loosened my tongue and enabled me to say things I would never have previously imagined. We have a disinhibiting effect on each other, where the usual super-ego bullshit gets shut down and we are able to just burn it up and let it rip. As Levinas was fond of saying, on est mieux à deux. Writing with four hands is better than two. It is fair to say that Memory Theatre wouldn’t have existed without Remainder and elements of C are all over it.

3:AM: Memory Theatre opens with the following three sentences: “I was dying. That much was certain. The rest is fiction” — well, is it?

SC: Yes, it is. Oh, there is tinnitus too.

This piece appeared in Bomb Magazine on 8 May 2014:

Nicholas Rombes by Andrew Gallix

Constraint as liberation, knife-wielding film scholars, and the human brain as total cinema machine.

Still from the ten-minute mark of The Foreigner, 1978, Amos Poe.

There was a time when movies lived up to their name. They moved along and, once set in motion, were unstoppable until the end — like life itself. What you missed was gone, lost forever, unless you sat through another screening, and even what you had seen would gradually fade away or distort along with your other memories. I recently happened upon a YouTube clip from a film I had first watched in 1981. I thought I knew the scene well, but it turned out to be radically different from my recollection: the original was but a rough draft of my own version, which I had been mentally honing for more than three decades. Such creative misremembering — reminiscent of Harold Bloom’s “poetic misprision” — is now threatened by our online Library of Babel.

According to Nicholas Rombes, who is spearheading a new wave of film criticism, movies surrendered much of their “mythic aura” when they migrated from big screens to computers via television. Indeed, since the appearance of VCR, spectators have been able to control the way movies are consumed by fast-forwarding, rewinding, and — most importantly, at least for digital film theorists — pausing. If such manipulations run counter to the magic evanescence of the traditional cinematic experience, Rombes manages to recast the still frame as a means of creative defamiliarization and re-enchantment. In 10/40/70: Constraint as Liberation in the Era of Digital Film Theory, he freezes movies at ten, forty, and seventy minutes. The resulting motionless pictures take on the eerie quality of Chris Marker’s 1962 masterpiece La Jetée, famed for its cinematic use of still photography. But soon the frozen frames Rombes burrows into start to move again — and in mysterious ways. They are rabbit holes leading to subterranean films within films.

In the bowels of an appropriately warren-like cinema, I met up with Rombes, whose criticism, artwork, and fiction are taking on the shape of a beautifully intricate Gesamtkunstwerk. Over several (too many?) espressos, we mapped out the treacherous critical terrain he excavates in this latest book. The danger “of staring too long into frozen images” and the fear of being swallowed up by gaps between frames were visible in his eyes.

Andrew Gallix For you, digital film theory is an attempt to retrieve something — “traces of something that was always there, and yet always hidden from view.” From this perspective, the 10/40/70 method has led to a significant discovery: the importance of what you call “unmotivated shots” — shots that do not strictly advance the storyline but, rather, contribute to the general mood. You go so far as to say that such moments, when directors seem to be shooting blanks, are “at the heart of most great movies.” In The Antinomies of Realism, critic and theorist Fredric Jameson argues that the nineteenth-century realist novel was a product of the tension between an age-old “storytelling impulse” and fragments through which the “eternal affective present” was being explored in increasingly experimental ways. Can we establish a parallel here with your two types of shots — plot versus mood? Are these unmotivated shots the expression of a film’s eternal affective present, perhaps even of its subconscious?

Nicholas Rombes This opens up a really fascinating set of questions about cinema’s emergence coinciding with the height of realism as both an aesthetic and as a general way of knowing the world. I’ll backtrack just a bit. In his 1944 essay “Dickens, Griffith, and the Film Today,” Sergei Eisenstein explored the relationship between Dickens-era realism and montage in cinema as pioneered by D. W. Griffith, specifically in his use of parallel editing. Eisenstein quotes Griffith explicitly acknowledging that he borrowed the method of “a break in the narrative, a shifting of the story from one group of characters to another group” from his favorite author, Charles Dickens. And that tension between the ever-present affective experience of watching a film or reading a book and the internal world of narrative time is beautifully explored in Seymour Chatman’s Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film. He draws a distinction between “story” (events, content) and “discourse” (expression). I prefer Chatman to Jameson here only because there is a boldness and a confidence to Chatman’s structuralist rendering with its charts, diagrams, and timelines. But yes, the messy correlation between the informational mode of a film still and the affective mode is a mystery. For me, a sort of enforced randomness — selecting the seventy-minute mark, no matter what — is an investigative tool for prying open this mystery. The element of chance is key. This method of investigation is opposed to hermeneutics, insofar as it approaches the text backwards. That is, rather than beginning with an interpretive framework, it begins with a single image I had no control over selecting. Whatever I’m going to say about the image comes after it’s been made available to me, rather than me searching for an image to illustrate or validate some interpretation or reading I bring to it.

AG The seventy-minute-mark screen grab of The Blair Witch Project (1999) just happens to be “the single most iconic image of the film,” but such serendipity is rare. In the case of a monster movie like The Host (2006), for instance, the 10/40/70 method fails to yield a single picture of the creature. As a result, your approach tends to defamiliarize films by pointing to the uncanny presence of other films within them — phantom films freed from the narcotic of narrative:

Such moments could be cut or trimmed without sacrificing the momentum of the plot, and yet the cast-in-poetry filmmakers realize that plot and mood are two sides of the same coin and that it is in these in-between moments — the moments when the film breaks down, or pauses — where the best chances for transcendence lie. […] It is in moments like these that films can approximate the random downtimes of our own lives, when we are momentarily freed from the relentless drive to impose order on chaos.

As this quote makes clear, your constrained methodology is “designed to detour the author away from the path-dependent comfort of writing about a film’s plot, the least important variable in cinema.” It is often a means of exploring the “infra-ordinary” — what happens in a film when nothing happens, when a movie seems to be going through the motions. One thinks of Georges Perec, of course, but also of Karl Ove Knausgaard, who recently explained that he wanted “to evoke all the things that are a part of our lives, but not of our stories — the washing up, the changing of diapers, the in-between-things — and make them glow.” When such in-between moments lose their liminality, do they become “moments of being” (to hijack Virginia Woolf’s expression) during which a movie simply is?

NR I think they do, and I very much like that phrase from Woolf. At the heart of this is the notion that films — all films — are documentaries in the sense that they are visual records of their own production. In a narrative film, for instance Ben Wheatley’s A Field in England (2013), we have a documentary record of so many things: the actors playing their roles; the landscape, whether natural or constructed; and of course filmic technology itself, insofar as the film is created with equipment that, in recording the narrative, is also leaving behind traces of itself. This is much easier to see in older films that are historically removed from us (i.e., a Griffith film “looks” filmic and reminds us of the technologies of, say, 1906 or 1907) or films that call for immediate and sustained attention to the process of their production (again, The Blair Witch Project). And, in that sense, as documentaries, I like to think that no matter how controlled, how airtight, how totalizing their efforts to minimize chance are, there will always be gaps, fissures, eruptions of the anarchy of everyday life. Even in something so small as the accidental twitch of an actor’s face, or the faint sound of a distant, barking dog that “shouldn’t” be in the film but is, or the split-second pause in a actor’s line and the worry that crosses her face that suggests she is really thinking about something else, something far apart and far away from the movie at hand. And so that’s one of the things I’m hoping to capture in pausing at ten, forty, and seventy minutes, though any numbers would do.

AG What was experimental in the context of the nineteenth-century novel has long been deemed conservative in the field of film. This, you argue, is due to “the near-total triumph of montage,” which “mutilated reality” through its depiction of “fractured time.” But Eisenstein-style dialectic montage is now the “dominant mode of advertising and a tool of media industry” — think “fast-paced cutting and MTV.” This led, by way of opposition, to the rise of neo-realist “long-take aesthetics,” ushered in by digital cinema, paradoxically a technology once thought to “represent a final break with the real.” Could you talk us through this?

NR The single-shot films of the Lumière brothers, though most lasted less than a minute, contained no cuts: they were continuous, real-time shots. These early films are often discussed as “actualities,” which is not helpful in that it suggests that cinema evolved out of this into its “inevitable” status as narrative/fiction, a supposed higher-order form of storytelling. Although it’s been an enormously productive way to think about early single-take cinema, it’s also created a binary that privileges so-called artifice (“art”) over so-called naive representations of reality. For André Bazin, long-take aesthetics, based in the Lumière films, are in some ways a moral act, one that had the radical potential to reveal, rather than to obscure, God’s created world. In his 1955 essay “In Defense of Rossellini,” he wrote:

[T]o have a regard for reality does not mean that what one does in fact is to pile up appearances. On the contrary, it means that one strips the appearances of all that was not essential, in order to get at the totality in its simplicity.

It’s easy to see why Bazin came under such withering assault by the post-structuralists in the 1960s and 70s, for whom words like “essential” were anathema, and for whom reality itself was always already a construct. And yet, a society gets the technology it deserves, and Bazin could only praise the long takes he was given — those in the films of Orson Welles, for instance, or Theodor Dreyer. This was an era when the typical motion picture camera magazine only held enough film for a ten to twelve-minute shot. So I would say that we have come full circle. Films like Alexander Sokurov’s Russian Ark (2002) show that narrative film can be made without any montage.

Still from the forty-minute mark of The Foreigner, 1978, Amos Poe.

AG One of your sources of inspiration was Roland Barthes’s 1970 essay, “The Third Meaning: Research Notes on Some Eisenstein Stills.” Do you share the French critic’s view that a static movie frame is neither a moving image nor a photograph?

NR Yes. One of the things Barthes suggests in that essay is that a “still is the fragment of a second text whose existence never exceeds the fragment; film and still find themselves in a palimpsest relationship without it being possible to say that one is on top of the other or that one is extracted from the other.” With digital cinema all sorts of wonderful complications come into play: in what sense, say, are film frames “frames” in digital filming, processing, and projection? And what’s the ontological status of an image that exists as ones and zeros? But no matter what the technology, the idea is the same: a “stilled” image from or of (in the case of a still versus a frame) a motion picture exists at a weird threshold, and, Barthes suggests, we might as well say that it’s not the paused image that’s extracted from the film, but the film itself which is extracted from the paused image. That’s the secret world I hoped to enter through intense scrutiny of an individual frame. This secret world, however, is perilous, and my own experience dwelling for so long in these film frames is that the tug of motion is sometimes still alive in them, perhaps like a cadaver that suddenly shudders for a moment with a trace of life. I found the experience altogether unsettling and even frightening.

AG Have you ever considered applying the 10/40/70 method to movies you’d never seen before? What kind of result would that produce, in your view?

NR I very much like this idea — sort of like flying blind. Without the context of having seen the movie to appreciate not just its plot but its texture and mood, the 10/40/70 method would coerce me into focusing even more on the formal qualities of the three frames in question. This would be especially true if it was a film that I not only hadn’t seen, but also had never even heard of before. Stripped of context, I wonder if the frames would assume something more akin to the status of photographic images, truly “stilled” in a way that’s impossible if you’re already familiar with the film.

AG Could you comment on the pleasing congruence between theory and practice — the “frozen moving image” being, as you point out, “the ultimate long take”? Something similar happens in the “Intermission” chapter, where your text mimics the split edit technique under discussion. In fact, one could argue that the 10/40/70 method itself produces a series of textual approximations of split edits. Is this continuity between writing and film a quest for a cinematographic writing style?

NR The theorists who’ve meant the most to me — such as Julia Kristeva, Roland Barthes, Jean Baudrillard, Laura Mulvey, Robert B. Ray, bell hooks, Eugene Thacker — perform their ideas through the shape and tenor of their prose, and that’s something I’ve aspired to, especially in 10/40/70, where the split edits between formal analysis, personal reflection, and theory hopefully generate, if only in flashes, the same sort of feeling you get when a film suddenly bares its teeth and shows you that it wasn’t what you thought it was. But I will also say there is a dark gravity at work in certain of the film frames, perhaps because portions of the book were written during a very low point for me. The film frame — motionless — doubling as a long take was an idea born of desperation, of staring too long into frozen images.

AG You quote André Bazin, for whom the power of a movie image should be judged “not according to what it adds to reality but to what it reveals of it.” Do you agree that this would provide an excellent description of your own analytical method, which is all about revealing something as yet unseen? On at least a couple of occasions, you acknowledge that there is “very little to say about [a] scene that is not outstripped by the scene itself.” On others, however, you adopt a more hands-on approach — by projecting a scene from The Passenger (1975) onto Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974), or by splicing together a movie and a novel — as though the 10/40/70 constraint were no longer enough.

NR Well, I do think some films theorize themselves and suffer from the words we use to untangle them. I’ve gotten in some terrible rows with colleagues about this over the years. In fact, one of the sections I deleted from the book described a knife fight between a fellow graduate student and myself at Penn State in 1992. It was about Wild at Heart (1990). After a long night of arguing and drinking Yuengling, I said something like, “that movie doesn’t need your theory because it’s already theorized itself,” then there was some unfortunate language that escalated into an actual, awkward fight with knives. Some film moments are diminished, rather than enlarged, by the words we bring to bear on them. As I’m answering this question I’m reading a novel by Jeff VanderMeer called Annihilation, and there’s a moment when the narrator realizes the enormity of the mystery she’s trying to understand: “But there is a limit to thinking about even a small piece of something monumental. You still see the shadow of the whole rearing up behind you.” For me, during the writing of 10/40/70, that shadow was the realization that the constraints I established were weak and insufficient against the tyranny of interpretive intention.

AG Your book is, among many other things, a rehabilitation of Bazin — what is his significance today? Could you explain what you mean when you claim that his “total cinema” is the “end point” of digital cinema?

NR Bazin was interested in excavating the desires that fueled the invention of moving images — desires that he suggests were based on a passion to create an utter and complete replication of nature. In his 1946 essay “The Myth of Total Cinema,” he suggests that what energized this desire was “the recreation of the world in its own image, an image unburdened by the freedom of interpretation of the artist or the irreversibility of time.” He says that the myth (i.e. the desire to replicate reality entirely) preceded the technology that made it possible. The tricky thing here is Bazin’s use of the term myth, which he doesn’t seem to equate with “false.” Instead, he almost suggests that this myth is achievable, as in his point that the flight of Icarus remained in the realm of myth only until the invention of the internal combustion engine. In this regard, Bazin occupies a fascinating and precarious place in film theory. While his approach has something in common with the later “apparatus theory,” which historicized film production, he decidedly didn’t share their assumptions about the ideological contamination of cinema’s very technology, instead framing that ideology within the larger and more important (for him) question of human desire and aspiration. By linking total cinema to a terminal, or end point, I’m wondering if we have achieved, on a symbolic level, Bazin’s notion of the recreation of the world in its own image. Doesn’t the surveillance state suggest this? On a practical level — and linking straight back to Bazin’s terms — it’s possible to have a camera, or multiple cameras, capture in a continuous, uninterrupted shot an object or a place and to keep recording this for as long and longer than you and I shall live. This one-to-one replication, to use Bazin’s term, of reality that unfolds contiguous with time itself, stretching decades with no interruption, with no need for interpretation, was not possible in Bazin’s era, except as a theory.

Still from the seventy-minute mark of The Foreigner, 1978, Amos Poe.