Gallix, Andrew. “Flogging a Dead Clothes Horse.” Interview by Thom Cuell. Minor Literature[s], 14 September 2018:

Punk is Dead: Modernity Killed Every Night is a wide-ranging collection of writing on punk, taking in memoir and theory, and examining the subject as a social movement, musical genre, artistic project, philosophy and political statement. Here, co-editor Andrew Gallix discusses the project, alongside his own experiences of Punk, and its impact on his later career.

In your own intro, you talk about punk being, of all youth movements, the most resistant to academic analysis (although, god knows, plenty of academics have tried to analyse it). Why is this? And what can we learn from the sheer number of books which have attempted to make this analysis?

Punk was a product of the failure of the counterculture and the advent of the tax-exile rock dinosaurs, who had become too remote — socially, musically and culturally — from their audience. So the whole issue of ‘selling out’ was high on the agenda, right from the start. Take Mark Perry, who decreed that punk died on the day The Clash signed to a major label (CBS) in January 1977. In the book, I argue that all the splinter groups that sprang from the original scene — Oi!, Two-Tone, the mod revival, the New Romantics, goth, anarcho-punk, etc. — were essentially attempts to recapture punk’s original spirit, untainted by compromise and commercialism.

No other youth cult had ever been so conscious of itself as a youth cult, and of its place in rock history. Sure, punk was a new beginning — Year Zero, and all that — but it was also a summation of the subcultures which had preceded it, and one of the traits it inherited was that quintessentially adolescent contrarian streak best expressed by Alan Sillitoe’s rebel without a cause, Arthur Seaton, in Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1958): “Whatever people say I am, that’s what I’m not”. Punk’s juxtaposition of contradictory signifiers — the swastika, say, and the hammer and sickle — was, in part, a means of ensuring that the straight adult world would not get it. Not that that was very likely, of course: the mainstream media did not have a clue what was going on. We forget just how wide the generation gap was in those days. The rush hour, in London, was a sea of men in pinstripe suits and bowler hats. Today, many of those people would have hipster beards and tattoos. (One of the unfortunate, unintended consequences of punk is that it largely killed off the generation gap — at least in pop cultural terms.)

There are, of course, other factors. Punk’s (frequently feigned) anti-intellectualism, which would lead some fanzine writers to add spelling mistakes to their articles, or the (at the time largely subterranean) influence of Situationism, which was obsessed with “recuperation”.

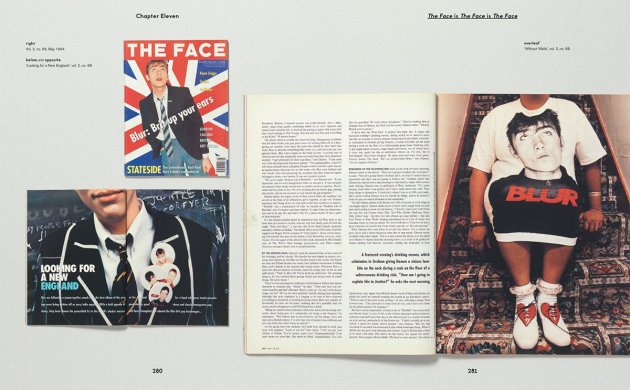

When they were not by insiders (Julie Burchill and Tony Parsons’ The Boy Looked at Johnny: The Obituary of Rock and Roll, 1978) or fellow-travellers (Caroline Coon’s 1988: The New Wave Punk Rock Explosion, 1977), early punk books were either mainly collections of photographs (Val Hennessy’s In the Gutter, 1978; Isabelle Anscombe’s Not Another Punk Book, 1978) or compendia of fanzine extracts (Julie Davis’s Punk, 1977). Punk, I think, succeeded in making any external discourse sound naff and illegitimate. Even Dick Hebdige’s Subculture: The Meaning of Style (1979) felt artificial, a bit earnest and fuddy-duddy: the work of a student. You have to wait until the late 80s / early 90s — when the original punk movement was effectively dead — to see the first thoughtful analyses appear (Greil Marcus’s Lipstick Traces in 1989 and Jon Savage’s England’s Dreaming in 1991).

What can we infer from the large number of books devoted to this subject? How incredibly rich such a short-lived movement was. There is a school of thought that sees punk as a simulacrum of Situationism, with the latter being the real McCoy. I beg to differ. I think punk’s strength was due to the fact that most of its practitioners had no idea where the references came from, so that ideas or gestures derived from Symbolism, Dada, Futurism, Surrealism or Situationism were embodied — lived out. Once the movement had died, all that background material needed to be unravelled, which is why of making many punk books there is no end.

Then there’s the fact that punk has never been out-punked — it has become a byword for ultimate rebellion. My contention is that it was also the last real avant-garde artistic movement of the 20th century.

Tell us a little about your own experiences of punk, and how that has impacted on your approach to culture.

I often say that punk had the same cultural impact on me as Surrealism or May 68 on earlier generations. I was 11 in 1976, when I first got into punk, so for me it’s also bound up with childhood memories, and growing up. It offered me a haven at a time when I was deeply unhappy. All of a sudden, I realised that there were others like me out there. It informs everything I do in some way or other.

Again, in your introduction, punk seems almost intangible — it’s hard to say when it coalesced, and when it began to shift into something more regimented. What approximate timespan do you set for the punk movement you discuss in your book, and events you use to pinpoint those moments?

Punk’s influence remains huge, and there are, of course, punk bands all over the world. Forming a punk band is almost a rite of passage for American teenagers. I know that some young people resent the title of my book. However, I’m not saying that you can’t be a punk today — my point is simply that the original British punk scene was very much a product of its socio-economic, political and artistic context. Walking around London with red hair in 1977 and in 2018 are two completely different experiences. The glory days were obviously 76-77 — how long you make it last beyond that is a question of opinion. The first punks are usually those for whom it ended earliest — with the 100 Club festival, say, the Bill Grundy affair or the Silver Jubilee. In a way, the whole history of punk, at least through 1981, has been one of newcomers denying that the phenomenon was dead, and reviving it. It’s interesting how the primal energy of tracks like “New Rose” or “White Riot” seems to be replicated in dozens of debut singles. As soon as a band can no longer sustain that level of energy or has become too sophisticated musically, the baton is passed on to the latest gang in town.

For me, it lasted 10 years. By 1986, I had to draw the conclusion that it was over and that I had very little in common with those who still described themselves as punks.

Punk is Dead blends theoretical work with personal recollections from fans and musicians and contemporary texts from fanzines and the music press — what effect were you hoping to create by bringing these three approaches to punk together?

To give a more nuanced idea of what punk was really like when it was still in the process of becoming. Once it had become what it was, it was dead. If a kid discovers Never Mind the Bollocks today, he or she will not have the same experience as someone who bought every single when it came out, lived through all the controversies, remembers when Boots and Smith’s wouldn’t even mention “God Save the Queen” in their charts, couldn’t see the band live, waited for what seemed like an eternity for the album to come out…

In Clinton Heylin’s Punk in the Year Zero (2016), attendees at early punk gigs talk about the visual presentation of the bands and their fans as much as, if not more than, the music they heard — presenting the Sex Pistols as a performance art group almost as much as a musical one. Is it this semiotic richness which sets punk aside from other movements, and gives it its unique character?

As you suggest, the performance art was produced by the band in conjunction with the audience. Breaking down the fourth wall was such an important part of the phenomenon. Punk was an artwork you could inhabit — it came close to abolishing the distinction between art and life, which had been the dream of all the avant-garde movements of the 20th century. It really was a revolution of everyday life.

You, and many of the contributors to Punk is Dead, are concerned with punk as a Gesamtkunstwerk, or all-embracing art form. Is that something you put down to the influence of Svengali-like figures such as Malcolm McLaren, or a broader impact of the culture which punk grew out of?

Both. McLaren was eager to create a scene around the Pistols that was partly modelled on Warhol’s Factory. In hindsight, it’s obvious that it wasn’t just about the bands, but also about the clothes, the fanzines, graphic design, the politics, the indie record labels. You’ve got to see the whole picture. That’s the artwork.

In your essays ‘Sexy Eiffel Towers’, and ‘Unheard Melodies’, you argue that some of the greatest punk bands never made any music at all, whether that is the punk-art interventions of Bazooka Productions, or the largely conceptual band L.U.V. If the music of punk is almost able to take a back seat to other aspects, which strand of punk has ultimately produced the greatest legacy?

That’s a tough question. All I can say is that many, if not most, of the early converts — Devoto and Shelley (Buzzcocks), T.V. Smith (The Adverts), Pauline Murray (Penetration) et al. — had read Neil Spencer’s first live review of the Pistols. They fell in love with the Romantic notion of a band that was into chaos rather than music. The same could be said about the CBGB scene: the future British punks were reading about bands like Television without really knowing what they sounded like. They had to dream their music into existence. The importance of the British music press in all this still hasn’t been adequately documented.

What was the most surprising thing about working on this anthology? Did you find yourself reconsidering any of your views on punk, or discovering anything you’d overlooked?

It reinforced my intuition that rock music lost its ‘telos’ after punk. Punk was a new departure, but also a summation of rock history and perhaps its end point. Everything that has happened since has been a kind of coda or postscript to that rock narrative that started in the mid-50s.

I was shocked by how exploitative and two-faced some ageing punks turned out to be. The kind of privileged popinjays who hide their lack of substance behind a puerile obsession with style, kidding themselves that they’re artists or anarchists while living off their inherited wealth. At times, working on this book felt like flogging a dead clothes horse.

It’s tempting to take the Zhou Enlai approach and say ‘too soon to tell’, but — what do you see as the lasting influence of punk?

Its influence is so all-pervasive that you no longer notice it. It’s important to remember that punk, at the time, was very much a minority interest. Almost everybody hated it. Now, all the influential people in the arts and media acknowledge its significance. It’s an extraordinary reversal of fortune.

Finally, Joe Strummer apparently threatened to beat Greil Marcus up for titling his anthology of punk writing In The Fascist Bathroom. Do you expect any similar responses from punk legends to anything in your book?

No, they’d be afraid of getting creases in their clothes.

In the book I describe Strummer as the Citizen Smith of punk — which he was, although that doesn’t mean he wasn’t very sincere and talented. I met him on two occasions. The last time he bought me a pint. Can’t say fairer than that.